Dealing with demand

In countries with a commercial bushmeat trade, the evolving demand from consumers presents an additional challenge.

Nguluka gained detailed insight into bushmeat consumption in Zambia’s capital while surveying Lusaka households and interviewing traders for a study funded by the U.S. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and U.S.-based big-cat conservation NGO Panthera. The research team estimated that more than 1,000 tons of illegal bushmeat is consumed in Lusaka every year, much of it coming from Zambia’s national parks.

“There is a perception that meat from wildlife is better quality than farmed animals, it’s not pumped full of drugs, it’s free range,” Nguluka said.

As well as perceived health benefits, the survey also found that bushmeat had a nostalgic quality for many Zambians, reminding them of their youth and offering an increasingly urbanized population a way to remain connected to their heritage. And, of course, there are those that simply prefer the taste.

The Zambian Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) and WCP have been tackling demand for bushmeat in two ways, the first through a hard-hitting media campaign titled “This Is Not a Game.”

“We went into this understanding that behavior change is very difficult to achieve,” Nguluka said. “You are asking people to unlearn decades if not generations of behavior, so it’s going to take time.”

Armed with their understanding of the motivations and preferences of bushmeat consumers in Lusaka, DNPW tasked a well-known Zambian creative agency to create a professional media campaign that went out on television, radio, newspapers and social media.

“It really needed to be a campaign for Zambians, by Zambians, speaking specifically to Zambian issues, and I think we achieved that,” Nguluka said.

The Zambian Department of National Parks and Wildlife’s (DNPW) “This Is Not a Game” campaign highlights the health risks from consuming illegal bushmeat. Image courtesy of This Is Not a Game.

The campaign focuses on three key messages: bushmeat is illegal, it’s dangerous, and it carries disease. The risk of disease has gathered increased weight in recent months since the outbreak of the global COVID 19 pandemic that is thought likely to have come from a bat.

Around 70% of new infectious diseases are zoonotic diseases that have jumped from other animals to humans. Scientists believe the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the recent Ebola crisis in West Africa both began with transmission from bats.

“I’m sure there were always transmissions and little outbreaks in villages, but when people died [in the village], the pathogen didn’t spread beyond,” said Fabian Leendertz, an infectious disease ecologist at the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin. “Now with the high connectivity, the pathogen has opportunity to go further and reach big cities.”

Leendertz has seen that an awareness of the risk of zoonotic disease can change behavior.

“In the Ebola crisis in West Africa, all the bushmeat markets were closed, nobody was eating meat, you didn’t find it in any restaurants anymore,” he said.

The curb on bushmeat hunting was short–lived, however. Once the Ebola crisis passed and temporary bans in West African countries were lifted, the need for affordable protein once more outweighed the perceived risk of zoonotic disease, and bushmeat markets have returned.

Nguluka said she believes messages about the risk of disease are getting through to the middle- and high-income earners who drive demand for illegal bushmeat in Lusaka. DNPW’s campaign uses local examples to get the message across, such as a 2011 anthrax outbreak in the hippo population along the South Luanga River. That incident led to more than 500 human anthrax infections in the region, with at least five fatalities, after hippo meat was consumed.

The second part of the campaign is to provide alternatives to illegal bushmeat in the form of legally farmed game. Unlike South Africa and Namibia, Zambia doesn’t have a successful game farming sector — a factor Nguluka says has exacerbated the illegal bushmeat trade. The prevalence of illegal bushmeat has meant that game farming for meat has simply not been profitable until now, and game farmers have focused on alternative income sources like trophy hunting.

“We’ve seen a shift in government policy and rhetoric around legal game meat, a big push for more legal game farming and for more Indigenous Zambians to get involved in game farming,” Nguluka said.

DNPW and WCP are helping to promote legal game meat and letting Zambians know where to find it. Access isn’t the only barrier, though. Illegal bushmeat traders often sell meat on credit, establishing longstanding relationships with customers. Nuances of the trade such as this highlight the need for locally specific research to understand bushmeat consumption.

Media campaigns like “This Is Not a Game” don’t come cheap. The original survey of Lusaka’s bushmeat consumption is soon to be repeated, and DNPW will find out just what impact its message has had.

“This Is Not a Game” is unusual in targeting urban Zambians, as other bushmeat campaigns have tended to focus mainly on the communities doing the hunting.

“The urban communities have a lot of power and determine what’s on the political agenda,” Nguluka said. “Being a developing country there are just so many pressing issues going on that [conservation] is not that high on the agenda.”

In Lusaka, 89% of those surveyed said they thought wildlife was important for Zambia, citing the foreign exchange earnings from wildlife tourists. Prices in national parks are set to make the most of the opportunities foreign tourists bring, but this makes them prohibitively expensive for many Zambians.

“If you’re not seeing [national parks], it’s very hard for you to care what’s going on in these areas or to have context,” Nguluka said. Part of her work focuses on encouraging young Zambians to work in conservation, creating awareness by providing access to stories for journalists, and encouraging Zambians who can afford it to visit the country’s national parks.

“We can’t expect them to care if they are not part of the conversation,” she said.

Citations

Lindsey, P., Taylor, W. A., Nyirenda, V., & Barnes, L. (2015). Bushmeat, wildlife-based economies, food security and conservation: Insights into the ecological and social impacts of the bushmeat trade in African savannahs. FAO/Panthera/Zoological Society of London/SULi. http://www.fao.org/3/a-bc610e.pdf

Lindsey, P. A., Nyirenda, V. R., Barnes, J. I., Becker, M. S., McRobb, R., Tambling, C. J., … t’Sas-Rolfes, M. (2014). Underperformance of African protected area networks and the case for new conservation models: Insights from Zambia. PLoS ONE, 9(5), e94109. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094109

Fa, J. E., & Brown, D. (2009). Impacts of hunting on mammals in African tropical moist forests: A review and synthesis. Mammal Review, 39(4), 231-264. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2009.00149.x

Brashares, J. S., Arcese, P., Sam, M. K., Coppolillo, P. B., Sinclair, A. R. E., & Balmford, A. (2004). Bushmeat hunting, wildlife declines, and fish supply in West Africa. Science, 306(5699), 1180-1183. doi:10.1126/science.1102425

Rogan, M. S., Lindsey, P., & McNutt, J. W. (2015). Illegal bushmeat hunting in the Okavango Delta, Botswana: Drivers, impacts and potential solutions. FAO/Panthera/Botswana Predator Conservation Trust. http://www.fao.org/3/a-bc611e.pdf

Angula, H. N., Stuart-Hill, G., Ward, D., Matongo, G., Diggle, R. W., & Naidoo, R. (2018). Local perceptions of trophy hunting on communal lands in Namibia. Biological Conservation, 218, 26-31. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.11.033

Naidoo, R., Weaver, L. C., Diggle, R. W., Matongo, G., Stuart‐Hill, G., & Thouless, C. (2016). Complementary benefits of tourism and hunting to communal conservancies in Namibia. Conservation Biology, 30(3), 628-638. doi:10.1111/cobi.12643

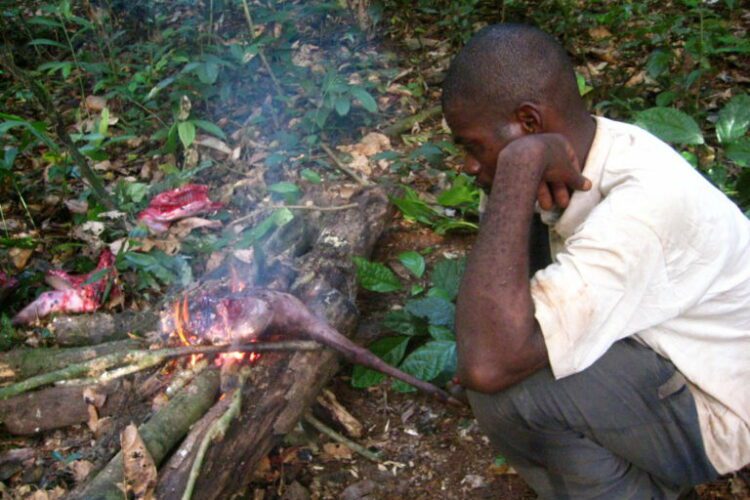

Banner image: Man roasting bushmeat. Image by Corinne Staley via Flickr (BY-NC-2.0)

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

Article published by Terna Gyuse

Animals, Biodiversity, Bushmeat, Conservation, Endangered Species, Environment, Environmental Crime, Environmental Education, Forests, Hunting, Law, Law Enforcement, Mammals, Over-hunting, Poaching, Protected Areas, Rainforest People, Rainforests, Tropical Forests, Wildlife, Wildlife Conservation, Wildlife Trade, Wildlife Trafficking

Africa, Central Africa, Southern Africa, West Africa, Zambia

PRINT

Source link : https://news.mongabay.com/2020/10/bushmeat-hunting-the-greatest-threat-to-africas-wildlife/

Author :

Publish date : 2020-10-26 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.