We had a tough summer season in Southern Africa, with El Nino induced drought that led to significant crop failures in the region. Zambia and Zimbabwe, among others, lost roughly half of the staple maize harvest. These countries must now rely on imports of maize to stabilize the domestic supplies for the year. We will likely remain in these challenging conditions until May 2025, when the new season harvest gets into the market.

The impact of the poor harvest is starting to show at household levels. For example, an article in Business Day Africa on August 20 indicates that:

“Elisa Magosi, the SADC Executive Secretary, has called for urgent humanitarian assistance, reporting that 68 million people across the region are now at risk of hunger. The crisis is particularly acute in Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, which have traditionally supplied food, especially maize, to East Africa. Zambia, previously a key maize exporter, is now dealing with a significant deficit exacerbated by the drought. The country seeks to import at least 500,000 tonnes of maize from Uganda to mitigate the shortfall.”

Zambia is not the only country seeking large maize imports. Consider Zimbabwe, the country’s maize harvest is down roughly 60% from the 2022-23 production season to an estimated 635,000 tonnes. This is the lowest harvest since the 2015-16 production season, another drought year.

This significant decline in Zimbabwe’s maize production means that the import needs will increase sharply. Zimbabwe’s domestic maize consumption is typically at about two million tonnes. Thus, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Pretoria-based analysts estimate that Zimbabwe may need to import at least a million tonnes in the new marketing year of 2024-25 is convincing (the 2024-25 marketing year corresponds with the 2023-24 production season). Such an import figure is a significant increase from Zimbabwe’s maize imports of 637,327 tonnes in the 2023-24 marketing year, all from South Africa.

Unlike the 2023-24 marketing year, where South Africa’s overall maize exports were 3,4 million tonnes, in the new 2024-25 marketing year, South Africa’s maize exports will likely fall to 1,85 million tonnes. This is on the back of a poor domestic harvest. South Africa’s maize harvest is estimated at 13,34 million tonnes, down 19% from the previous season because of the mid-summer drought. This volume comprises both white and yellow maize. White maize is about 6,35 million tonnes (down 26% year-on-year), and yellow maize is at 6,99 million tonnes (down 12% year-on-year).

These exports will primarily be for the Southern Africa region. In fact, between May and the first week of August 2024, South Africa had already exported 567k tonnes out of the expected 1,85 million tonnes. The principal beneficiary is Zimbabwe and a range of neighbouring African countries.

Admittedly, South Africa did not experience a sharp fall in production, unlike Zimbabwe or Zambia, where the domestic maize harvests are down by over 50%. Part of the reason is differences in farming practices and the improved seed cultivars in South Africa, among other factors. The significant difference is using improved seed cultivars, fertilizer, and agrochemicals. Irrigation is not a major factor, as only 10% of South African maize is under irrigation, and the rest is rainfed. This is similar to Zimbabwe’s maize proportion under irrigation.

In essence, we have spent the past few months highlighting the impact of the drought on farms, but now we are seeing it on the consumers. The next couple of months will likely be challenging in the region, with the hope for relief from the next season’s agricultural harvest. The preliminary estimates from various weather services suggest we may be moving to a La Nina period that would bring rain. Until then, the conditions outside South Africa are worrying.

Follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo).

Zambia’s maize production in the 2023/24 season is down by over 50% to an estimated harvest of 1,6 million tonnes because of the intense heat wave and mid-summer drought. The country must now import about a million tonnes of maize to meet its domestic annual needs.

The government has encouraged the private sector in the country to ramp up its effort to import maize. However, the challenge is that they want only non-genetically modified maize. Zambia still prohibits cultivating and importing genetically modified maize (GMO maize).

It is already a challenge to find white maize in the world market regardless of whether it is GMO or GMO-free, as the major producers are the Southern African region (South Africa specifically) and Mexico. Most of the world’s maize is yellow maize for animal feed.

The drought has hit the entire Southern Africa region. The Southern Africa region’s primary maize producer, South Africa, saw its harvest fall by 19% year-on-year to 13,3 million tonnes in the 2023/24 season. Still, South Africa could have about 1,5 million tonnes for the export markets. This is both white and yellow maize.

South Africa is out of the equation when considering GMO-free maize, as the country’s maize is roughly 85% GMO. Then Zambia will have to put its faith in Mexico and Tanzania for GMO-free maize supplies. Whether they will succeed in securing such supplies remains an open question. I am not as optimistic as these countries also face challenges in their production season.

Path forward

I think Zambia should consider adjusting its policies and permitting the importation of GMO maize, which can be transported directly to millers if they don’t want the grain to reach farmers. This is an approach Zimbabwe uses; thus, they are amongst the significant maize importers from South Africa.

In the medium term, however, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and many other countries in the region should consider reviewing their GMO policies. The Southern Africa region, and indeed, the African continent, must embrace technology and the newly improved seed cultivars to boost domestic production.

Admittedly, there are legitimate debates about the ownership of seeds and how smallholder farmers could struggle to obtain seeds in some developing countries. These are realities that policymakers in African countries should manage regarding reaching agreements with seed breeders and technology developers but not closing off innovation. Technology developers also need to be mindful of these concerns when engaging with various governments in African countries.

South Africa is the only exception that has embraced genetically modified crops since the 2001/02 season. The country has also enjoyed improvements in yields and is now a leading producer of grains in the region. For example, according to the data from the International Grains Council, South Africa produces about 16% of sub-Saharan maize, utilizing a relatively small area of an average of 2.5 million hectares since 2010.

In contrast, countries such as Nigeria planted 6.5 million hectares in the same production season but only harvested 11.0 million tonnes of maize, equating to 15% of the sub-Saharan region’s maize output. Irrigation has been an added factor in South Africa, but not to a large extent, as only 10% of the country’s maize is irrigated, with 90% being rainfed, making it similar to other African countries.

Notably, although the yields are also influenced by improved germplasm (enabled by non-genetically modified biotechnology) and improved low and no-till production methods (facilitated through herbicide-tolerant genetically modified technology), other benefits of genetically modified seeds include labour savings and reduced insecticide use as well as enhanced weed and pest control. Hence, with the African continent currently struggling to meet its annual food needs, using technology, genetically modified seeds, and other means should be an avenue to explore to boost production.

In essence, many African governments should reevaluate their regulatory standards and embrace technology. In the case of Zambia, we are now at an appropriate time for such reform, and the government must embrace change for the good of farmers and consumers. Zambia should take advantage of the available maize surplus in South Africa by adjusting its policies and permitting imports. Failure to do so will not necessarily hurt the South African farmers, as they will still have robust demand from Zimbabwe and continue to export there and other world regions such as the Far East. The people who will be at a loss are the Zambian consumers who have to be content with reduced maize supplies at higher prices.

A rethink of the seed policies is long overdue in the long term. The improved seed cultivars are part of the technologies that will help Africa’s agriculture adapt to climate change. Therefore, governments should think of it that way.

Follow me on X (@WandileSihlobo).

I am looking at the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) crop production data, and they have an interesting extract on Zimbabwe’s wheat industry.

The USDA forecasts Zimbabwe’s wheat production for the 2023/24 marketing year at 240,000 tonnes, up 37% year-on-year, which is very encouraging.

This is mainly supported by an expansion in the area planted and improved irrigation. The USDA states that “Zimbabwe’s wheat is nearly 100% irrigated and grown by commercial farmers who deliver their harvest to Zimbabwe’s Grain Marketing Board.”

Such an improvement in the harvest prospects will help reduce Zimbabwe’s wheat import needs. The country consumes roughly 410,000 tonnes of wheat a year. This means while production increased, Zimbabwe will still import wheat to fulfil domestic needs.

Major deviations

However, these USDA figures are miles apart from what the Zimbabwean government reported – a crop of 468,000 tonnes.

In a dataset stretching as far back as 1960, Zimbabwe has not produced a wheat harvest of over 400,000 tonnes. Thus, I am more inclined to believe the USDA figures for now and only observe the government estimate of 468,000 tonnes, with a major dose of uncertainty.

Had Zimbabwe expected such a major wheat harvest, continuous imports would not be needed to supplement the domestic needs. Yet, Zimbabwe continues to import wheat from various countries.

Also worth noting is that Zimbabwe is buying some wheat from South Africa. So far, in the 2023/24 marketing year, South Africa exported 21 832 tonnes of wheat to Zimbabwe.

With mixed-up production data like this, one should keep a close eye on this matter; better data should be available in the coming months.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo). E-mail: [email protected]

Zimbabwe was one of the countries I worried would have a maize supply shortage in 2023. This was after data from the Pretoria office of the US department of agriculture showed that Zimbabwe’s 2022/23 maize production would amount to 1.5-million tonnes, little more than half of the ample harvest of 2.7-million tonnes of the 2020/21 production season.

While this would have been a minor improvement on the 2021/22 production season’s maize harvest of 1.4-million tonnes, it would be 25% short of the country’s annual maize need of about 2-million tonnes. I feared Zimbabwe would have to import about half a million tonnes to fulfil its annual need and another half million tonnes to replenish its grain reserves, since the Zimbabwe Grain Marketing Board is mandated to maintain a minimum of half a million tonnes of strategic maize reserve in physical stocks.

Still, given the poor economic conditions in Zimbabwe I suspected that the board was unlikely to procure the half million tonnes strategic reserve in full within the 2023/24 marketing year (the marketing year corresponds with the 2022/23 production year). I therefore believed that at the very least imports would amount to about half a million tonnes. There are many countries Zimbabwe could rely on for imports, but neighbouring SA and Zambia are the usual suppliers in times of need.

However, looking at Zimbabwe’s maize imports from SA from May 2023 to the beginning of December, there are signs that import needs may be far lower than I anticipated. Over that period maize imports from SA amounted to only 164,123 tonnes. This is 67% lower than the amount I expected for the 2023/24 marketing year.

Admittedly, the marketing year has not yet ended; we still have three months to go before it terminates at the end of April. Still, if the historical data is anything to go by, imports — at least from SA — will fall below the volume I expected. I don’t have a clearer view of the figures out of Zambia, but I suspect they are also not significant. In addition, there is no clarity or published data on the maize import activities of the Zimbabwe Grain Marketing Board.

I believe that together with my US department of agriculture colleagues we underestimated Zimbabwe’s 2022/23 maize production and the opening stocks. Had we held a reasonably optimistic view on these, as did the country’s agriculture ministry, we would have ended up with a different forecast. If the shortfall was as significant as we expected, there would be severe food shortages by now.

After I shared my downbeat view on Zimbabwe’s maize production outlook in 2023, Zimbabwean friends on social media — @X — were upset that I was so pessimistic about the conditions and pointed me to the government data. I ignored the Zimbabwean maize production estimates as the government there has a history of being “economical with the truth”. But this time the government official projections appear to have come far closer to reality.

Overall, nothing is terrible here. It is always good to be surprised to the upside on matters of food production forecasts. We all want the region to thrive and be food secure. Zimbabwe seems to have been in a slightly better position, assuming nothing unusual happens in the next three months.

The outlook for the 2024/25 marketing year will depend on the crop now growing. I will comment on this later — and this time take the views of Zimbabwean government officials into account.

Written for and first appeared on Business Day.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo). E-mail: [email protected]

It is disappointing to see that in Kenya, President William Ruto’s government lost a case seeking the Court of Appeal’s nod to import Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) maize into the country.

President Ruto wanted to lift the ban on cultivating and importing GMO white maize in Kenya in response to growing food insecurity in Kenya. The country has struggled with drought in the recent past and remains a net importer of maize.

The liberalization of the Kenyan maize seed market would have benefited farmers in the same way as in South Africa, Brazil and the US. In fact, the sentiment towards the cultivation and importation of GMO crops is changing worldwide, partly because of the global food crisis and countries’ efforts to boost domestic production.

For example, at the beginning of June 2022, the Chinese National Crop Variety Approval Committee released two standards that clear the path for cultivating GMO crops. Now that this hurdle has been cleared, the commercialization of GMO crops in China is a real possibility.

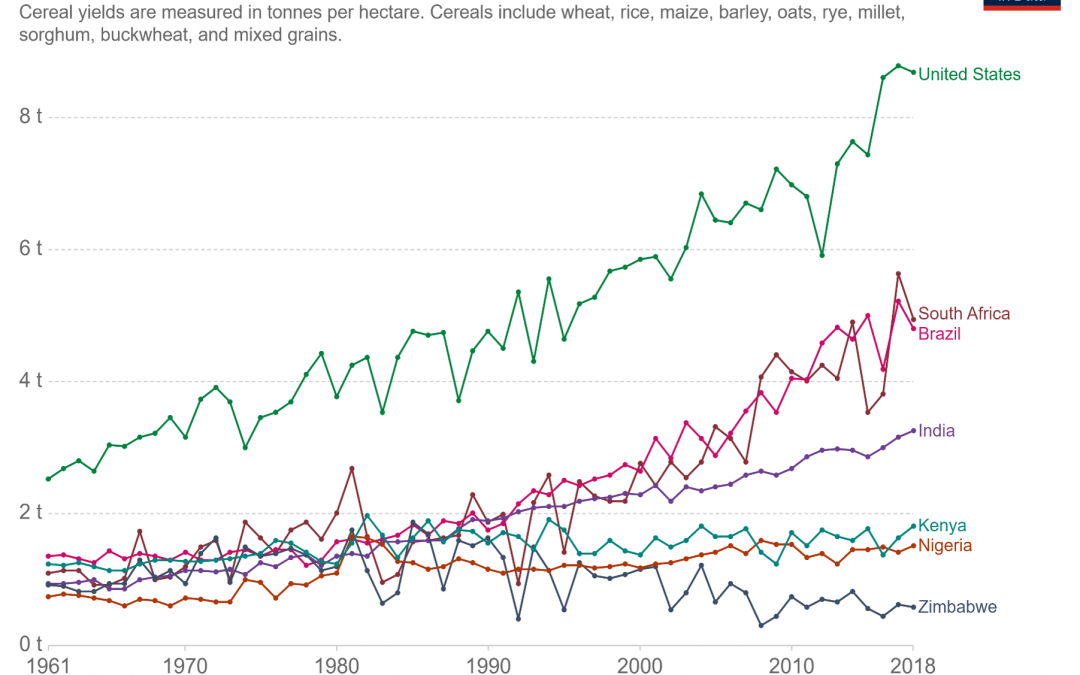

South Africa was an early adopter of GMO technologies. We began planting GMO maize seeds in the 2001/2002 season. Before their introduction, average maize yields in South Africa were about 2.4 tonnes per hectare. This has increased to an average of 6.3 tonnes per hectare in the 2022/23 production season. Meanwhile, the sub-Saharan African maize yields remain low, averaging below 2 tonnes per hectare.

While yields are also influenced by improved germplasm (enabled by non-GM biotechnology) and improved low and no-till production methods (facilitated through herbicide-tolerant GM technology), other benefits include labour savings, reduced insecticide use and enhanced weed and pest control.

With Kenya struggling to meet its annual maize needs and importing over half a million tonnes yearly, using new technologies, GMO seeds, and other means should be an avenue to boost production in future.

Significantly, allowing for imports of GMO maize from origins such as South Africa, the US, and South America would have helped soften Kenya’s domestic maize prices, which are currently double what we see in South Africa, trading around US$500 per tonne.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo). E-mail: [email protected]

Africa’s Agricultural Paradox

Wandile Sihlobo[i]

Remarks at the Africa-Israel Agriculture Dialogue

Stellenbosch, South Africa

24 April 2023

Good morning colleagues,

Thank you to The Brenthurst Foundation and the American Jewish Committee for organizing this gathering at a crucial juncture in our economic development journey. The theme “Africa’s Agricultural Paradox” is befitting given the vision, desire and intention of our country, and the continent, to chart an inclusive and sustainable development path.

I want to make a few remarks on Africa’s agriculture before we move into what promises to be a fruitful discussion.

We all know that agriculture is an essential driver of employment and economic activity in most African countries. For example, roughly 60% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa is engaged in smallholder farming. About 23% of sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP comes from agriculture.

However, the strategic role of the sector as a driver to advance economic development has been hampered by a number of exogenous factors. The Russia-Ukraine war and Covid 19 continue to compromise the resilience of its agricultural sector. These major challenges come against the backdrop of existing problems that have already been affecting the agricultural sector in the past.

These include,

Climate change with its associated shocks, such as frequent droughts, flooding, famine, etc.

Biosecurity, primarily the weaknesses in managing animal diseases, e.g., highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), foot and mouth disease (FMD), and African swine fever.

We see pest infestations, such as the fall armyworm (FAW), and locusts, regularly in the East Africa region – whose frequency and intensity is also emerging as a consequence of changing weather patterns.

Low farm and off-farm productivity remains a major challenge and will continue to be a constraint even in this environment where most people are excited about the promise of the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Lack of adequate infrastructure, which increases transaction costs for farmers and agribusinesses operating in the continent of Africa.

Conflicts or wars, like what we are witnessing in East Africa, Mozambique in Southern Africa, and most recently in West Africa.

Fragmented food value chains

More recently, the rising input costs, partly because of the Russia-Ukraine war

Therefore, we need to tackle these challenges collectively and holistically in order to maximize the value of the agricultural sector in Africa.

We are a continent that struggles with high unemployment, poverty and low economic growth. We know from the literature that growth in agriculture is two to three times more effective at reducing poverty than an equivalent amount of growth generated outside agriculture.

Moreover, the advantage of agriculture over non-agriculture in reducing poverty is largest for the poorest individuals in society and extends to other welfare outcomes, including food insecurity and malnutrition.

So, what to do with all these challenges?

There are some policy considerations that I believe the African Agricultural Ministers here in the room with us can reflect on during the sessions.

In my view, four overarching issues should remain critical priorities for African governments:

First, the African governments must improve land governance, which is fundamental for long-term investments. We know that roughly 86% of all the continent’s rural land plots are still unregistered. We cannot expect any meaningful levels of investment, infrastructure development and farm productivity improvements in an environment in which land ownership and use rights are inadequate.

Suppose I may use my home country, South Africa, as an example, in areas with strong property rights. In that case, we continue to see secure use and ownership rights that provide incentives to engage in robust agricultural activity, which essentially sustains our food security and exports.

Meanwhile, in the former homelands regions of South Africa, with weak land governance, such robust agriculture is non-existent to a large extent. Of course, I am simplifying a more complicated argument because these rights need to be couched in other important variables and factors such as infrastructure, institutions, skills, and agricultural finance. But you get the main point.

Second, African governments must create an enabling policy environment. This includes clear competition and merger regulations, tax incentives for SMEs, a regulatory environment that promotes quality standards in input and output markets, predictable trade policies, digitalization of customs procedures, and harmonization of border regulations.

Third, once we have the above matters adequately addressed, we could focus on attracting long-term investment in Africa’s agriculture. Here, I am not only talking about the private sector investments by local (MSMEs) and global investors but also public sector investments, i.e., public infrastructure expansion of border infrastructure, roads and connectivity (IT).

Fourth, we must also address the issue of informality in Africa’s agriculture and food industry. In an article I co-authored with agricultural economists Edward Mabaya of Cornell University and Lulama Ndibongo Traub of Stellenbosch University, we noted that “across all of the continent’s regions, except southern Africa, informal employment as a percentage of total employment in the agricultural and non-agricultural sector is above the global average of 64% for emerging and developing markets economies.

More than 80% of the continent’s population relies on open-air, largely informal markets for their food. Poor sanitary conditions in many of these markets raise concerns about food safety for households that depend on them.

Suppose African countries are to ensure resilient and sustainable agrifood systems. In that case, they must upgrade food value chains by shifting production and employment from informal micro-enterprises to formal firms offering wage employment with income security and health benefits for employees. This will also ensure improvements in food safety within the system.”

In essence, colleagues, my message this morning is that we need Policy Reform and Implementation, Investments, and Technical Innovation, which leads to Competition and Efficiency gains in Africa’s agriculture.

Notably, the African government, this time around, should increase the pace of policy reform to continue stimulating private sector investments. They must also ramp up public investments to strengthen regional food value chains, AfCFTA implementation, etc.

Thank you for listening; I look forward to our discussion.

[i] Senior Fellow, Department of Agricultural Economics, Stellenbosch University.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo). E-mail: [email protected]

Although I continue to argue that South Africa should expand its agricultural export markets to new frontiers such as India, China, Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea, amongst others, the export drive should not be at the expense of the existing markets.

We should actively engage with existing markets to promote further growth of exports of South African agricultural products. The engagement needs not only to focus on the EU and Asia, both crucial regions for our export growth, but also on the rest of the African continent.

The African continent remains the largest export market for South Africa’s agriculture. In the record agricultural exports of US$12,8 billion in 2022, the African continent accounted for 37%. Importantly, this was not an anomaly. The continent has accounted, on average, for 38% of South Africa’s agricultural exports by value per annum over the past five years.

Unlike the other regions South Africa exports to, where the composition of products is predominantly fruits, beef, wool and wine, maize is the leading export product in the African continent. Other products exported to the rest of the African continent include apples, wheat, animal feed, prepared foods, wine, fruit juices, soybean oil, sunflower oil, alcoholic beverages, and soybean oilcake.

The leading markets were Botswana, Namibia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Eswatini, Zambia, Angola, Nigeria, and Mauritius. Except for Nigeria, these markets are within the Southern African Development Community’s Free Trade Area, which has benefited South Africa greatly. Moreover, these markets’ infrastructure and proximity advantage contributes to the concentration of South African agricultural exports to this region.

As we advance this trade relationship with the Southern African Development Community and the rest of the African continent, there will need to be various industry and government engagements to keep warm relations.

Such an approach would help to avoid erroneous policy decisions, such as what Namibia and Botswana did in 2022 by blocking vegetable imports from South Africa. This policy action negatively affected the South African farmers that had increased production in anticipation of the regional demand.

Simultaneously, the consumers in Botswana and Namibia were also left with little choice as their typical supplies were suddenly out of the shelf. Through close collaboration with the regional business community and government, we would address trade concerns without drastic steps by the neighbouring countries, which understandably want to prioritise the interests of local producers and consumers.

Aside from the long-term trade policy direction, the demand for South African agricultural products will likely increase in the 2023/24 marketing year within the African continent. The 2023/24 marketing year corresponds with the 2022/23 production season. In the previous season, countries such as Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Tanzania had decent supplies of grains and other foodstuffs on the back of a reasonably good harvest (although lower than the bumper crops of the previous season).

Reports from FEWS NET suggest that dry and hot weather conditions in the earlier part of the 2022/23 production season negatively impacted crops in southern Angola, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and northern and eastern Madagascar. Moreover, there are growing concerns that the higher fertilizer prices have led to lower usage by farmers in these countries, which would ultimately undermine the yields.

The first glimpse of these countries’ crop conditions and import needs will be through maize production data from the USDA in the coming months. For Zimbabwe, production forecasts are yet to be made available. Still, Zimbabwe would require sizeable imports if the crop drops below the previous season’s harvest of 1,6 million tonnes, given its annual maize needs of 2,1 million tonnes. The possible suppliers to Zimbabwe will be Zambia and South Africa. Zambia’s maize production forecasts are yet to be released. Still, there is an expected 15,6 million tonnes for South Africa, up 1% y/y, which should enable South Africa to export at least 3 million tonnes of maize in the 2023/24 marketing year.

Another country that is worth keeping an eye on is Kenya. The latest estimates from the United States Department of Agriculture place Kenya’s 2023/24 marketing year maize imports at 750 000 tonnes. This is up mildly from the previous season’s maize imports of 700 000 tonnes. The primary hope for Kenya is to import maize from Tanzania and Zambia, which collectively accounted for 98% of Kenya’s maize imports in the 2021/22 marketing year. South Africa has minimal participation in the Kenyan maize market because of the prohibitive anti-genetically modified crop regulations.

I have used maize as an example, but if maize crops faced production challenges, then one can assume that there are similar challenges in other crops and vegetables. This means South African producers should closely monitor the African market and increase supplies where market conditions allow. Beyond these near-term seasonal matters, the South African agribusiness community, as the major exporters of the produce from South African farms, along with the government officials, should maintain close engagement with counterparts across the rest of the African continent as this is not only a diplomatic consideration but also a commercial matter.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo). E-mail: [email protected]

I don’t know much about Kenya’s new president, William Ruto, but I already like his approach to agriculture. In the first week of October Ruto’s administration lifted the country’s ban on the cultivation and importing of genetically modified (GM) white maize.

Ruto, a scientist with a PhD, made this change in response to growing food insecurity in Kenya. The country has struggled with drought in the recent past and remains a net importer of maize.

There will be an assessment of each GM trait by the Kenyan Biosafety Authority before actual imports and cultivation can occur. Assuming some of this scientific legwork has already been done, we could see imports start in the next few months.

Just as well. In the 2022/2023 season, Kenya needs to import a substantial volume of maize, estimated at about 700,000 tonnes. This is roughly unchanged from the previous season, which also posted poor domestic production.

In the 2021/2022 season several sub-Saharan African countries, including Zambia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and SA, had ample maize harvests. This made it easy for them to meet Kenya’s import needs, with Tanzania and Zambia leading the way.

However, this year things are different. Tanzania’s maize harvest is down roughly 16% year on year to 5.9-million tonnes due to sparse rainfall at the start of the season combined with armyworm infestations and reduced fertilizer usage in some regions because of prohibitively high prices.

The fall in production and firmer domestic consumption means Tanzania will have less maize to export. The numbers I have seen thus far point to available maize for export of just 100,000 tonnes. This is well below the previous season’s exports of 800,000 tonnes, which saved Kenya when the country was most in need of maize.

The country in the region with the most abundant supply of maize at present is SA, whose maize exports for the 2022/2023 season are forecast at 3.5-million tonnes. SA struggled to access the Kenyan market for many years because of its ban on imports of GM products. But Ruto’s move has changed all that, offering a new opportunity for SA exporters (provided the Kenyan Biosafety Authority gets its ducks in a row).

In the future, the liberalization of the Kenyan seed market should benefit its farmers in the same way as in SA, Brazil, and the US. In fact, the sentiment towards the cultivation and importation of GM crops is changing worldwide, partly because of the global food crisis and countries’ efforts to boost domestic production.

For example, at the beginning of June, the Chinese National Crop Variety Approval Committee released two standards that clear the path for cultivating GM crops. Now that this hurdle has been cleared, the commercialization of GM crops in China is a real possibility. The EU is also reviewing its regulations on cultivating and importing GM crops, an essential step in a region that has long had an anti-GM stance.

As I have pointed out in these pages before, SA was an early adopter of GM technologies. We began planting GM maize seeds in the 2001/2002 season. Before their introduction, average maize yields in SA were about 2.4 tonnes per hectare. This has increased to an average of 5.6 tonnes per hectare in the 2020/2021 production season.

Meanwhile, the sub-Saharan African maize yields remain low, averaging below 2 tonnes per hectare. While yields are also influenced by improved germplasm (enabled by non-GM biotechnology) and improved low and no-till production methods (facilitated through herbicide-tolerant GM technology), other benefits include labor savings and reduced insecticide use, as well as enhanced weed and pest control.

With Kenya struggling to meet its annual maize needs, using new technologies, GM seeds and other means should be an avenue to boost production in the future.

Follow me on Twitter (@WandileSihlobo). E-mail: [email protected]

Source link : https://wandilesihlobo.com/category/africa-focus/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-08-20 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.