What’s new? In February 2020, South Sudan’s two main belligerents began forming a unity government pursuant to a peace deal inked a year and a half earlier. But the pact is fragile, smaller conflicts are still ablaze and the threat of return to full-blown civil war remains.

Why does it matter? Forthcoming elections could test the peace deal severely. Looking further ahead, conflict will continue to plague South Sudan until its leaders forge a political system that distributes power more widely. The cost of cyclical fighting since 2013 has been steep: hundreds of thousands dead and millions uprooted from their homes.

What should be done? South Sudan’s leaders should strengthen pre-election power sharing and broaden the peace deal to include other parties. They should not rush to polls, if conflict looms, and seek a political settlement decentralising governance and cementing national power sharing. Civil society and external partners should continually advocate for these steps.

Fêted at birth a decade ago, South Sudan is failing. It suffered a brutal civil war from 2013 to 2018, exposing a country whose foundations were weaker and divisions deeper than its well-wishers envisioned. The war has quietened thanks to a peace deal, signed in 2018 by the two main belligerents. But the path to stability is unclear. Not only could the pact collapse, but it does little to calm an insurgency in the nation’s south or local violence elsewhere. Elections looming as soon as 2022 threaten to inflame tensions between its signatories. Moreover, South Sudan’s winner-take-all political system ill suits a country that requires consensus among major blocs to avert cyclical power struggles. South Sudanese need to get through elections, which may well require some form of pre-election power-sharing pact. They also need a revised political settlement. While prospects of that for now appear slim, the country’s reform-minded elites, civil society and external partners should still work toward fairer power sharing at the centre and greater devolution.

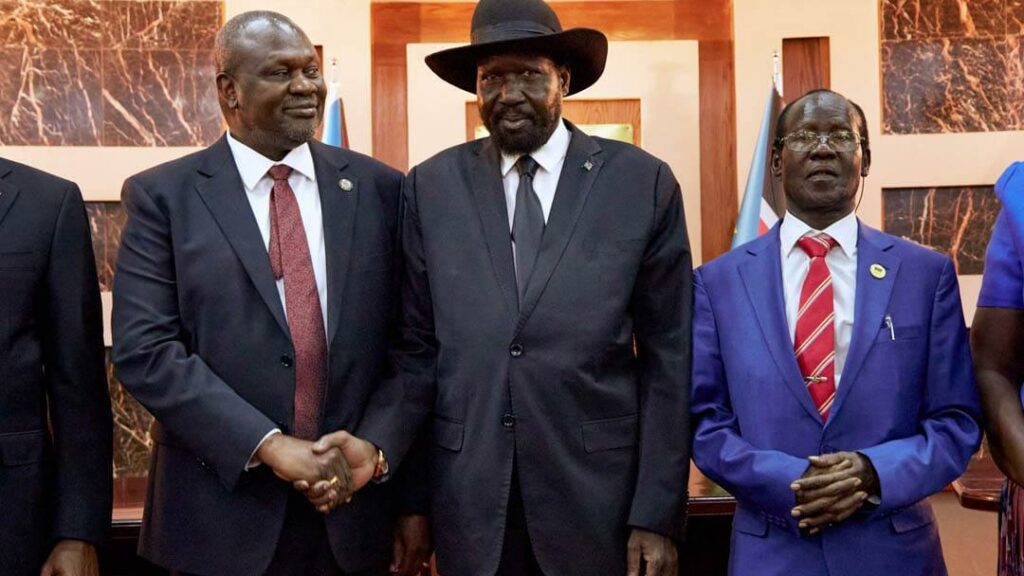

While the country’s stark development needs were apparent at independence, South Sudanese and outsiders significantly downplayed its political woes, especially its ethnic cleavages. That proved a mistake. Just two years after the triumphal inauguration of the world’s newest country in July 2011, South Sudan collapsed at the centre, as the rival camps loyal to President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar turned against each other in bloody combat that shattered the ruling party. The resultant fighting, which has mostly taken place along ethnic lines, has killed as many as 400,000 people. Since the 2018 peace deal, which moved forward in February 2020 when Kiir and Machar agreed to form a unity government, the ceasefire between the two main warring parties has held but the pact has accomplished little else.

With the country so broken, the first challenge is maintaining and expanding upon the ceasefire. The peace process requires endless maintenance by external actors, notably East African leaders, with their attentions consumed by efforts to prevent a slide back to war between the two chief factions. Meanwhile, groups that fought under Machar’s banner could well split off and return to conflict. Communal violence in parts of the country is running up the death count, particularly in remote rural areas. An insurgency led by Thomas Cirillo, a veteran general in the South’s previous struggle against Khartoum, has also taken root in the southern Equatoria region, including near the capital Juba, and risks spreading. Regional and other diplomacy aimed at bolstering the ceasefire between Kiir and Machar is critical, but those involved should do what they can to prevent splinter conflicts and broaden the peace process to include Cirillo.

The next hurdle is preventing renewed violence in the run-up to or aftermath of promised elections. The polls are expected to pit Kiir’s coalition against Machar’s in what some call a final showdown. That the peace deal culminates in such a winner-take-all contest is a potentially fatal flaw. Even if fighting does not erupt before the polls, as occurred in 2013 when Kiir’s faction exchanged fire with Machar’s, setting off the civil war, an all-or-nothing vote risks dissolving the agreement’s political settlement by locking the losers out of power. Regional leaders and other external actors have to tread a fine line: pushing South Sudanese parties toward elections while showing flexibility when necessary to create space for them to reach consensus on key decisions. At the same time, they should keep a watchful eye on pre-election dynamics and encourage dialogue between Kiir and Machar. If the poll looks set to be fraught, particularly if, as appears likely, both men decide to run, regional leaders should push for a pre-election deal that guarantees a share of power to the loser.

Getting past the vote without a descent into further violence will be hard enough, but the bigger challenge lies in finding a settlement among South Sudanese that lays the groundwork for a sustainable peace. Regional leaders and diplomats are short of ideas as to how to steer South Sudan out of its pattern of peace deals that fall apart. They privately express little optimism or vision for South Sudan’s future. Nor is such a vision to be found among South Sudan’s major donors, which also once championed its cause and now foot the huge humanitarian bills, if not the ultimate costs, for its failings.

Solutions could be found in the reshaping of South Sudan’s political architecture toward more consensual forms of governance.

Solutions could be found in the reshaping of South Sudan’s political architecture toward more consensual forms of governance. Constitutionally, the country is a majoritarian democracy. Yet in practice, peace in South Sudan requires consensus among elites and communities, which often mobilise as well-armed ethno-political blocs, notably within Kiir’s Dinka people, the nation’s largest, Machar’s Nuer, the next largest, and Equatorians, a diffuse grouping of ethnicities in the nation’s south. Even the concept of a centralised state in South Sudan butts against the reality of a country lacking basic institutions and infrastructure including roads. Maintaining stability is impossible without broad accommodation.

A more durable political settlement requires reducing the winner-take-all stakes. Options could include institutionalised power sharing at the centre or an elite bargain to rotate power among key ethno-political groups or regions. Some form of decentralisation is almost certainly necessary. Such remedies cannot cure all the country’s ills, but they might provide its elites a sense of shared interest that has eluded them over decades of brutal conflict. Prospects for such reform for now appear slim, with powerful elites, including Kiir and Machar themselves, for the most part opposed. Still, until space opens for official dialogue on reform, South Sudanese civil forces should advance discussions in whatever venue they can, including outside the state arena. South Sudan’s external partners should be ready to facilitate such dialogue, if asked. Long-term peace in South Sudan almost certainly requires the country’s leaders to agree on a more equitable division of power and resources, no matter how long it takes them to do so.

Juba/Nairobi/Brussels, 10 February 2021

Peer deep, then deeper, and the number of South Sudan’s problems only appears to grow. Years of civil war have devastated the country, leaving up to 400,000 people dead and displacing four million– one in every three South Sudanese – either inside the country or across its borders.[fn]Crisis Group Statement, “A Major Step Toward Ending South Sudan’s Civil War”, 25 February 2020. Crisis Group has covered the Sudanese and, subsequently, South Sudanese conflicts in depth since 2002. See, inter alia, Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°147, Déjà Vu: Preventing Another Collapse in South Sudan, 4 November 2019; and Crisis Group Africa Reports N°s 270, Salvaging South Sudan’s Fragile Peace Deal, 13 March 2019; 217, South Sudan: A Civil War by Any Other Name, 10 April 2014; 172, Politics and Transition in the New South Sudan, 4 April 2011; 106, Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement: The Long Road Ahead, 31 March 2006; and 96, The Khartoum-SPLM Agreement: Sudan’s Uncertain Peace, 25 July 2005. For various population estimates, see “South Sudan”, Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook, last updated 1 February 2021; “South Sudan”, World Health Organisation (WHO), n.d.; and “South Sudan”, UN Data, n.d.Hide Footnote South Sudan requires massive food aid to prevent chronic famine.[fn]The World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that 60 per cent of South Sudanese struggle to feed themselves. WFP requires roughly $1 billion per year to reach nearly half of the population with food assistance. See “South Sudan Emergency” and “South Sudan Emergency Dashboard October 2020”, WFP, November 2020. See also Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°124, South Sudan: Instruments of Pain (II): Conflict and Famine in South Sudan, 26 April 2017.Hide Footnote Its politicians have plundered oil revenue that many hoped would pay for a brighter future.[fn]South Sudanese politicians acknowledge that theft of state oil revenues has been widespread since 2005. Crisis Group interviews, 2018-2020; and Crisis Group analyst’s interviews in a previous capacity, 2016-2018. South Sudan ranked 179th of 180 countries listed in Transparency International’s 2019 Corruption Perception Index. President Salva Kiir admitted in 2012 that “an estimated $4 billion are unaccounted for or, simply put, stolen by current and former officials, as well as corrupt individuals with close ties to government officials. Most of these funds have been taken out of the country and deposited in foreign bank accounts”. Letters Kiir sent to dozens of current and former officials demanding funds be returned, 12 May 2012, signed template on file with Crisis Group. For two major investigations of distinct billion-dollar corruption scandals, see Simona Foltyn, “How South Sudan’s elite looted its foreign reserves”, Mail & Guardian, 3 November 2017; Mark Anderson and Michael Gibb, “As South Sudan Seeks Funds for Peace, a Billion-Dollar Spending Spree”, Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, December 2019.Hide Footnote The country lacks the most basic infrastructure. Despite a 2018 peace deal, including a ceasefire between the main belligerents that has largely held, violence blights large swathes of the country, with ruling elites never far from turning against each other and going back to war.

South Sudan is thus often absorbed in trying to keep its head above water. Its foreign partners, fatigued by conflict and aid bills, must apply recurrent pressure on parties to stop fighting or to stick to a peace deal. National elections loom as early as 2022, worrying officials and diplomats who wonder if the country will be ready, that is, if the unity government that brought President Salva Kiir and his arch-rival Riek Machar together in 2020 has not imploded by then due to disputes between them, including over the poll itself. Amid the constant efforts to halt violence, ward off starvation, keep the stuttering peace deal on track and push the country toward a vote, outside powers as well as many South Sudanese seem to have lost sight of any vision for longer-term stability in South Sudan.

A strategy for escaping the current quagmire must go beyond conflict mitigation to address South Sudan’s failed political model, which concentrates authority in the centre and unleashes a king-of-the-hill power scramble. The winner-take-all governance system fuels constant tensions among elites, already sore from decades of bloody infighting, leaving the country vulnerable to relapse into war. Many community, rebel and religious leaders, government officials and women’s groups across the country express not only deep frustration with the national leadership but also the belief that the solution lies in greater autonomy and representation for South Sudan’s diverse communities and regions. They echo tenets of the liberation movement that preceded the country’s 2011 secession from Sudan: decentralisation, enshrined in the first constitution, and the promise that South Sudanese would share the country as equals.[fn]Crisis Group interviews and Crisis Group analyst’s interviews in a previous capacity, Juba, Wau, Malakal, Yambio, Ezo, Yei, Aweil, Rumbek, Yirol, Raja, Kodok, Tonga, Ganyiel, Kapoeta, and refugee camps in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, 2016-2020.Hide Footnote Shared and devolved power might be a credible path out of crisis, albeit one strewn with obstacles – notably, elites who often conduct themselves more as war entrepreneurs than statesmen.

This report proposes strategies for addressing South Sudan’s immediate problems and then takes a longer view, charting options for the country to escape its perennial cycles of conflict. Research involved dozens of interviews across South Sudan, in Horn of Africa capitals and in New York, Washington, Brussels and London, as well as by remote means.

On 9 July 2011, thousands of South Sudanese thronged the capital of what would soon be Africa’s 54th state to celebrate their independence and what many hoped would be the capstone of a five-decade struggle for liberation from successive repressive governments in Khartoum. South Sudanese had voted by a landslide in a referendum six months earlier to carve out a new state from Sudan following protracted talks between South Sudanese leaders and representatives of Omar al-Bashir’s Khartoum administration.

Despite the joy on display at the independence celebrations, few thought the road ahead would be easy or smooth. South Sudan at its outset was a place of abject underdevelopment and hardship, with many of its citizens’ daily lives marked by chronic hunger, rampant insurgent violence and security force brutality. The plight of women was especially dire, with maternal health and female education scores among the worst in the world. Years after independence, a South Sudanese girl was still more likely to die in childbirth than to finish school, according to the UN.[fn]“Turning Five with South Sudan”, UNICEF, 6 July 2016. Nearly 10 per cent of children die before the age of five, and over 30 per cent of children under five are malnourished. One in seven women die giving birth. Over 70 per cent of adults (and 84 per cent of women) are illiterate, and 42 per cent of civil servants have no more than a primary education. South Sudan ranks 186th of 189 countries on the UN’s Human Development Index. See “About South Sudan”, UN Development Programme (UNDP), n.d.; Human Development Report 2019, UNDP, 2019; and “South Sudan: Human Development Indicators”, UNDP, n.d. “South Sudan has some of the worst health outcome indicators globally”, according to the WHO. See “Country Cooperation Strategy at a Glance: South Sudan”, WHO, 2018. For more health indicators, see “South Sudan”, WHO, op. cit.Hide Footnote

Perhaps even more pernicious than the development challenges were deep ethnic divisions lurking just beneath the triumphalism that accompanied the new nation’s founding.

Perhaps even more pernicious than the development challenges were deep ethnic divisions lurking just beneath the triumphalism that accompanied the new nation’s founding. South Sudanese had fought a destructive conflict for decades both against the Sudanese government in Khartoum and, more often than not, against each other. Salva Kiir and Riek Machar, today South Sudan’s president and vice president, respectively, fought each other on rival sides, mobilising combatants from the Dinka (Kiir) and Nuer (Machar) ethnic groups, from 1991 until 2002.[fn]By one estimate, the Dinka, South Sudan’s largest group, comprise 35.8 per cent of the population, while the Nuer, the second largest, make up 15.6 per cent. “South Sudan”, Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook, op. cit. There are no reliable demographic figures in South Sudan since the country has yet to conduct a census.Hide Footnote During this period, many other armed groups in South Sudan took part in the factional melee.

South Sudan’s 437-page development blueprint – published a month after independence and described by the finance minister as “the first comprehensive plan for the Republic of South Sudan” was blunt about the prospects of overcoming ethnic and political divisions:

There remains deeply rooted tribal animosity. This has been identified as one of the ongoing causes of ethnic conflicts, created by distinct identity clashes and perceived dominance in social and political space. Some communities thus feel superior and others feel inferior and marginalised. Peacebuilding will require embracing diversity and finding ways for communities to live and work together in harmony.[fn]“South Sudan Development Plan 2011-2013”, Government of the Republic of South Sudan, August 2011. “During the first years of independence, South Sudan will focus on state and nation building, deepening peacebuilding, preventing conflict, improving security and bringing about a process of rapid economic development to reduce poverty”.Hide Footnote

Still, at independence, most South Sudanese officials and outsiders seemed oblivious to the danger that the country’s elites would hurt its chances with violent power struggles, despite their long history of infighting. The country’s development plan envisaged that ethnic and political animosity might lead to local violence but did not foresee civil war or state collapse.[fn] Ibid.Hide Footnote A “worst-case scenario” imagined by the UN and U.S. considered the risk that a repressive one-party petrostate might emerge and fight border wars with neighbouring Sudan, but it shied away from predictions of implosion.[fn]“South Sudan Transition Strategy 2011-13”, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), June 2011; “Sudan Work Plan 2011”, UN Office of the Coordinator for Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), November 2010. Even by November 2013, a month before the civil war began, the UN continued to fear border war between Sudan and South Sudan as the worst-case scenario. “South Sudan Consolidated Appeal 2014-2016”, OCHA, 14 November 2013.Hide Footnote

Donors thus devoted their efforts to strengthening the central government through capacity building and military reforms, believing that in time South Sudan would be resilient enough that the private sector would want to invest in the country more heavily. The UN Security Council explicitly tasked the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) to deploy a peacekeeping operation focusing mostly on supporting the country’s institutions. Major donors, led by the U.S., lined up to help, to the tune of billions of dollars.[fn]The UN Security Council’s instructions included an injunction to help with “establishing the conditions for development … with a view to strengthening the capacity” of the government.Hide Footnote The UN, U.S. and UK especially underwrote efforts to help the government mould the country’s many militias into a professional army.[fn]The U.S. alone spent an estimated $150-300 million on efforts to bolster and reform the Sudan People’s Liberation Army from 2006 to 2010, according to a former U.S. and UK security consultant who investigated the sum. Richard Rands, “In Need of Review: SPLA Transformation in 2006-10 and Beyond”, Small Arms Survey, November 2010, p. 32. For a review of the literature on security sector reform in South Sudan, see Joshua Craze, “The Politics of Numbers: On Security Sector Reform in South Sudan, 2005-2020”, London School of Economics, November 2019.Hide Footnote

But South Sudan plunged into civil war, nevertheless. The political waters appeared calm just after independence, perhaps because South Sudan’s new ruling-party leaders were bound together by illicit self-enrichment from leaky state coffers.[fn]See footnotes 3 and 21. For more on the patronage system before the 2013 civil war, see Alex de Waal, “When Kleptocracy Becomes Insolvent: Brute Causes of the Civil War in South Sudan”, African Affairs, vol. 113 (July 2014). De Waal argues that the patronage scheme collapsed after Juba’s 2012 decision to halt oil production – a hardball tactic used against Sudan when negotiating pipeline fees – leading the South’s elite to fracture and thence to civil war.Hide Footnote Soon enough, however, the scars of decades of internecine conflict reopened. The loose alliance that held the ruling party together began to unravel as the clique associated with Kiir’s home area and Dinka kin tightened its grip on the levers of government and the party. As power became concentrated in fewer hands, this circle grew more prone to wielding repression and violence in order to keep it. Those targeted or squeezed out saw few options for redress other than taking up arms.

South Sudan’s quick disintegration into political fratricide and ethnic violence thus did not come from nowhere.

South Sudan’s quick disintegration into political fratricide and ethnic violence thus did not come from nowhere. It was born of deeply poisoned internal politics that evolved over decades of struggle against Khartoum.

A. Decades of Cleavages

There was a time prior to South Sudan’s independence when its elites appeared unified in purpose. In the 1950s, a distinct nationalism brought together various political factions in what is today South Sudan. They opposed the terms of Sudan’s own independence in 1956, arguing that Britain’s decision to attach the South’s largely non-Muslim and Black African peoples to the majority-Muslim North would end in neglect by Khartoum.[fn]Britain originally governed “black African” Southern Sudan under a separate administration from the rest of Sudan and planned to integrate the Southern Sudanese provinces into its East African colonies. During this time, British administrators instituted a “closed districts” policy that isolated the South from the Muslim North for much of the colonial period. Britain’s subsequent decision in the decade leading up to the 1956 independence to place Southern Sudanese under Khartoum’s rule was considered an act of betrayal by many southern elites, who feared that Northern Sudanese would inevitably dominate them. Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, Sudan: A Country Study (Washington, 2015), pp. 26-31.Hide Footnote

But the South’s own latent political divides soon opened up. Southern solidarity began to dissolve when Joseph Lagu, who had led the South’s first insurgency (the so-called Anyanya) and signed a 1972 peace agreement granting the area autonomy, campaigned to subdivide the new entity into its three colonial-era provinces – Equatoria, Bahr el Ghazal and Upper Nile – after he lost the leadership position to Abel Alier, an ethnic Dinka, in assembly elections in 1980.[fn]Under the terms of the 1972 accord, an elected Southern Sudan assembly chose the president of the High Executive Council that ruled Southern Sudan, though by the 1980s Nimeiri frequently intervened. Lagu pulled out at the last minute of the 1980 race to back another rival in a failed attempt to block Alier’s bid. By 1980, ethnic Dinka comprised 47 per cent of the regional assembly. See Mom Kou Nhial Arou, “Regional Devolution in the Southern Sudan, 1972-1981”, PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, September 1982.Hide Footnote Backed by politicians in his native Equatoria region, Lagu argued that the Dinka, the South’s biggest ethnic group, unduly dominated Southern politics. He pushed for the South to be broken up to dilute what he considered the Dinka’s excessive power.[fn]See Joseph Lagu, “Decentralization: A Necessity for the Southern Provinces of the Sudan”, reprinted in his memoirs, Sudan: Odyssey through a State from Ruin to Hope (Omdurman, 2006). In this pamphlet, Lagu published a table detailing alleged over-representation of ethnic Dinka in Southern government positions.Hide Footnote

Sudan’s president, Jaafar Nimeiri, exploited these divisions. Siding with Lagu in 1983, he split the South into three regions, dissolving the autonomous government created by the 1972 deal. Amid Southern infighting, Nimeiri also declared that Islamic law would apply throughout Sudan.[fn]Both Lagu and Alier published their own accounts of this period in their respective memoirs. Alier’s is titled Southern Sudan: Too Many Agreements Dishonoured (London, 1990). For other accounts, see Arop Madut-Arop, The Genesis of Political Consciousness in South Sudan (2012); and Arou, “Regional Devolution in the Southern Sudan, 1972-1981”, op. cit. On the 1983 division of the South into three, known as kokora (an ethnic Bari term for “division”), and its lasting impact on Equatorian-SPLM relations, see Rens Willems and David Deng, “The Legacy of Kokora in South Sudan”, PAX, November 2015; Mareike Schomerus, “Violent Legacies: Insecurity in Sudan’s Eastern and Central Equatoria”, Small Arms Survey, June 2008. On all the above, see also Crisis Group Africa Report N°236, South Sudan’s South: Conflict in the Equatorias, 25 May 2016.Hide Footnote These moves led to widespread unrest and the creation of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), headed by John Garang, an ethnic Dinka, who led the South’s second insurgency against Khartoum.

Even as Garang presented himself as representative of all Southerners against Khartoum’s rule, the South remained internally divided. Many Equatorians viewed the SPLM as a Dinka force opposed to the newly formed Equatoria region. Together with other minority groups, they felt alienated by abuses committed by Dinka-dominated forces against them.[fn]Ibid. The Dinka, by contrast, blamed Equatorians for ethnic expulsions following the 1983 kokora division, including in Juba.Hide Footnote The SPLM also broke up into multiple factions after Machar, then a top ethnic Nuer SPLM commander, challenged Garang’s leadership in 1991, creating a split that led to years of ethnic wars, primarily involving Dinka and Nuer – a preview, in some ways, of South Sudan’s civil war that began in 2013. Khartoum continued to exploit these divisions, supporting proxy and splinter forces against Garang’s SPLM across the South, while Garang leveraged regional backing and Western support to amplify his own power internally.[fn]Garang’s skill at mobilising external support for his cause had the perverse effect of lessening the SPLM’s efforts over the years to build domestic legitimacy and governing capacity. The SPLM thus often acted more like a predator than a liberator in areas it occupied. During the 1990s, the Ethiopian, Eritrean and Ugandan militaries quietly built up the SPLA’s armoury and fought alongside it in the South against the Sudanese army, while Kenya supplied safe haven for elites. The U.S., which eventually became Garang’s most important backer, encouraged all these regional actors in their support for the movement. In the mid-1990s, Washington supplied an extra $20 million in military assistance to “front-line states” Uganda, Ethiopia and Eritrea that were backing the SPLM. USAID also took the unusual step of routing its aid to the South through the rebel movement. By 1998, one scholar writes, “the United States had become the principal backer of the SPLA, through USAID and Congress”. See Alex de Waal, “The Politics of Destabilisation in the Horn, 1989-2001”, in Alex de Waal et al. (eds.), Islamism and Its Enemies in the Horn of Africa (London, 2004), p. 241. Congress also acknowledged its long-running support for the SPLM. See Ted Dagne, The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country, Congressional Research Service, 2011. U.S. support was a product of its desire to counter former President Omar al-Bashir’s Islamist government in Khartoum. The SPLM also benefitted from close ties in Washington built by U.S.-educated SPLM founder John Garang.Hide Footnote

Divisions persisted even after war ended.

Divisions persisted even after war ended. The 2005 peace deal between Sudan and the South, brokered by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) regional bloc, set the South on course for its independence referendum.[fn]Crisis Group warned in 2005 that the SPLM needed to swiftly engage with other Southern armed and political movements to prevent renewed fighting in the South after the accord. See Crisis Group Report, Sudan: The Khartoum-SPLM Agreement: Sudan’s Uncertain Peace, op. cit.Hide Footnote But many Nuer and other minority anti-SPLM militias across the South remained outside the agreement. Some of them remained explicitly aligned with Khartoum.[fn]The 2005 peace deal gave Khartoum and the SPLM joint military control over various cities and towns for the six-year interim period. Khartoum kept some of its southern militias deployed in South Sudan during this time, leading to clashes, especially in Malakal in 2006 and 2009. See Aly Verjee, “Sudan’s Aspirational Army: A History of the Joint Integrated Units”, Centre for International Governance Innovation, May 2011. For the fate of the many anti-SPLM southern militias after 2005, see John Young, “The South Sudan Defence Forces in the Wake of the Juba Declaration”, Small Arms Survey, 2006; and Alan Boswell, Nanaho Yamanaka, Aditya Sarkar and Alex de Waal, “The Security Arena in South Sudan: A Political Marketplace Study”, London School of Economics, December 2019.Hide Footnote

B. Pre-independence Inclusion, Post-independence Exclusion

After Garang’s sudden death in 2005, Kiir took over the SPLM and pursued a big tent strategy of political inclusion. He worked to bring Southern factions together primarily by handing out plum positions and cash in a massive petrodollar-fuelled arrangement.[fn]Under the wealth-sharing protocol of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, the new semi-autonomous Southern Sudan government earned 50 per cent of the oil revenues produced inside Southern Sudan, giving the long-time rebel SPLM sudden access to billions of dollars. For more on the South’s patronage network, see de Waal, “When Kleptocracy Becomes Insolvent”, op. cit.; Alex de Waal, The Real Politics of the Horn of Africa (Cambridge, 2015); Boswell et al., “The Security Arena in South Sudan”, op. cit.; Craze, “The Politics of Numbers”, op. cit.; and Clemence Pinaud, “South Sudan: Civil War, Predation and the Making of a Military Aristocracy”, African Affairs, vol. 113 (April 2014).Hide Footnote This approach worked to some degree. In 2006, he negotiated the Juba Declaration with the SPLM’s main enemy in the South, the South Sudan Defence Forces, led by Paulino Matip, who then came to Juba as South Sudan’s deputy commander-in-chief until his death years later. Current and former SPLM dissidents also joined Kiir in Juba, attracted by the oil riches in the treasury and the shared aim of secession from Sudan. Tens of thousands of fighters from a collection of disparate militias joined the ranks of the South’s military, still known then by its rebel moniker, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA).[fn]See Lesley Anne Warner, “The Role of Military Integration in War-to-Peace Transitions: The Case of South Sudan (2006-2013)”, PhD thesis, King’s College London, 2018.Hide Footnote

Kiir’s accommodation strategy reached its apex in 2010, during the run-up to the South’s independence vote. While several new insurgencies sprang up, led by disgruntled local leaders who would soon be armed by Khartoum, Kiir managed to contain the fallout by once again promising to broaden the tent. In October 2010, just months ahead of the independence vote, he hosted an “all parties” political conference in Juba with 23 parties, negotiating a ceasefire with insurgent forces by promising the opposition a broad-based interim government and an inclusive constitutional review process once independence was achieved.[fn]All Southern Sudanese Political Parties’ Conference Communiqué, 17 October 2010, on file with Crisis Group.Hide Footnote

After the January 2011 referendum, the interlude of South Sudanese unity dissipated almost immediately. Independence secured, the SPLM, still led by Kiir and Machar, moved quickly to monopolise power, dishonouring its October 2010 deal with other parties. Just days after the referendum vote, Kiir renewed military offensives against opposition forces, breaking the ceasefire. The ruling party then ignored the rest of its commitments in the 2010 pact, including the inclusive constitutional review and the broad-based interim government.[fn]Abraham Awolich, “Political Parties and the Push for Political Consensus”, The Sudd Institute, 2 December 2015, p. 10.Hide Footnote

The SPLM elites then trained their sights upon one another as they jockeyed for the country’s all-important presidency. Since many party insiders viewed Kiir as an interim leader following Garang’s death, he came under frequent leadership challenges from senior party opponents who hoped to rule in his place. These opponents included Machar, then his deputy, and the party’s secretary general, Pagan Amum.[fn]Garang’s widow, Rebecca Nyandeng, now a vice president for the Former Detainees party, also aligned with Kiir’s challengers.Hide Footnote With tensions boiling over, Kiir postponed a March 2013 party conference, then sacked Machar as vice president that July and dismissed many other top cabinet and party officials.

The dispute split the party elite into three main factions, largely along the ethnic and geographical lines that later defined the contours of the civil war’s early period.[fn]Kiir’s camp feared the Nuer-led challenge because ethnic Nuer dominated the military ranks after the integration of the Khartoum-backed anti-SPLM militias from 2006 onward. Elites from other ethnic minorities largely divided their allegiances at the time, without a clear champion. Machar and the Garangists were at times in cahoots against Kiir, but most of the Garangists declined to join Machar’s armed rebellion, with some later forming the Former Detainees faction. See also Crisis Group Report, South Sudan: A Civil War by Any Other Name, op. cit.; and Alan Boswell, “Insecure Power and Violence: The Rise and Fall of Paul Malong and the Mathiang Anyoor”, Small Arms Survey, October 2019.Hide Footnote Kiir drew his core support largely from prominent Dinka from Bahr el Ghazal, while Machar commanded the loyalties of influential Nuer, with a separate, ethnically heterogenous challenge led by SPLM Secretary General Pagan Amum from the late Garang’s faction of party elites, including some from Garang’s Greater Bor Dinka community. Rather than agreeing on how South Sudanese could share power, the country’s most powerful elite had instead entered a mad scramble for it.[fn]One senior member of Kiir’s government at the time, directly involved in brokering the October 2010 all-parties conference, linked the 2010 pact’s dissolution to the ensuing civil war. “South Sudan needed an all-party transition”, said the former senior official, but those within the SPLM “didn’t want to share power”. If Kiir and Machar had honoured the 2010 agreement, the leadership disputes that later split the SPLM “could have been sorted out civilly away from the state arena”, he said. “It was a case of novices playing with fire”. Crisis Group correspondence, August 2020.Hide Footnote

The result was civil war. When SPLM delegates finally met to choose their leader in December 2013, after repeated delays, Machar and Kiir’s other key rivals boycotted the session, accusing the president of rigging the process for the party’s presidential nomination in his favour. Shots rang out on the evening of 15 December, as Dinka and Nuer elements of the elite presidential guard tasked with protecting both Kiir and Machar exchanged fire. Gunmen loyal to Kiir scoured Juba for ethnic Nuer, massacring civilians, while Nuer forces fled to the bush, later forming the SPLM/A-In Opposition under Machar.[fn]Crisis Group Report, South Sudan: A Civil War by Any Other Name, op. cit. See also “Final Report of the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan”, African Union, October 2014.Hide Footnote

C. A Shaky Peace

The war dragged on for years. After bitter fighting and failed talks, Machar returned to the capital in April 2016 under an initial peace deal, with over a thousand fighters in tow, but he fled again three months later after fresh clashes broke out between the rival forces in Juba. Government forces pursued him for weeks until he and his remaining guard of near-starving fighters crossed into the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the UN airlifted him to safety. Under pressure from the Obama administration, which at the time hoped to push Machar out of politics, regional countries arranged for him to be placed under de facto house arrest in South Africa, where he sought medical treatment.[fn]Crisis Group Report, Salvaging South Sudan’s Fragile Peace Deal, op. cit. For more on the 2016 collapse and Machar’s subsequent flight to the Democratic Republic of Congo, see Alan Boswell, “Spreading Fallout: The Collapse of the ARCSS and New Conflict along the Equatorias-DRC border”, Small Arms Survey, May 2017.Hide Footnote This arrangement, however, failed to stem the Machar-led insurgency against Kiir, which spread into Equatoria and western Bahr el Ghazal, areas where Kiir’s forces had already launched devastating scorched-earth counter-insurgencies.

Peace talks did not resume until late 2017, when regional governments realised again that there was no clear path to ending the war except by bringing Machar back to the negotiating table.

Peace talks did not resume until late 2017, when regional governments realised again that there was no clear path to ending the war except by bringing Machar back to the negotiating table.[fn]Talks did not resume immediately, as Kiir appointed Taban Deng Gai, Machar’s top negotiator, to replace Machar in the peace deal. The U.S. endorsed the move and then pushed for Machar to be placed under house arrest in South Africa. Machar maintained the loyalty of the vast majority of opposition fighters, leading to the resumption of talks. See Crisis Group Report, South Sudan: Salvaging South Sudan’s Fragile Peace Deal, op. cit.Hide Footnote After months of futile attempts to recreate a unity government, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed handed the mediation over to Sudan’s then-president, Omar al-Bashir, who worked with Kiir’s ally, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, to push the two sides to compromise. The parties surprised many by quickly settling into a ceasefire after signing a September 2018 accord laying out the timeline for formation of a unity government.

Getting to the unity government, however, has been a slog. Kiir and Machar failed to unify their forces and form a unity government by May 2019 as promised, as the mediator Bashir fell to a popular uprising capped by a coup. The two South Sudan leaders missed another deadline to form the unity government in November 2019, before regional leaders, headed by the new Khartoum government, brokered Machar’s entry into the power-sharing arrangement in February 2020. While the ceasefire has largely held, nearly all its provisions – including unification of forces into a single army, establishment of a new national assembly, creation of a transitional court of justice and economic reforms, to name but a few – remain unfulfilled.

D. Shattered Country, Shattered Plans

South Sudan’s horrific civil war exposed how the young country still requires broad political consensus to hold together. At independence, South Sudan’s presidential system lacked negotiated norms to ensure that those outside power had an incentive to believe in the new state rather than rebel against it. As SPLM ruling elites competed for oil funds, they also fell out with one another. The result was state collapse. The peace deals that followed have not overcome the problem of political exclusion, as Kiir has dominated the levers of government and oil revenues under power-sharing arrangements that have quickly eroded. Rather than the unitary state donors envisaged, the country now more closely resembles a Wild West contested by armed factions.

Donors, stunned by the scale and ferocity of the country’s epic collapse and then fatigued by the years-long effort to keep South Sudanese alive while trying to end the war, now regularly admit that they have no clear plan for finding peace, despite the substantial sums still devoted to humanitarian aid.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, major Western donor state officials, 2018-2020.Hide Footnote Disgust with the country’s elite is especially palpable in Washington, where many considered themselves South Sudan’s “midwife” due to their support for the SPLM.[fn]The U.S. was the SPLM’s most important backer, prodded by a strong lobby in Washington. See Rebecca Hamilton, “The wonks who sold Washington on South Sudan”, Reuters, 11 July 2012.Hide Footnote Donors eventually suspended the state-building project altogether and are unsure whether and how to restart it, given their deep aversion to assistance that strengthens the hand of the now-despised elite class.[fn]“The magnitude of the humanitarian, social and political crisis spurred by violence that erupted in South Sudan in December 2013 has drastically changed the context for development. In response, USAID redirected its assistance, shifting from state-building to more directly assisting the people of South Sudan”. “Our Work”, USAID, 9 September 2020.Hide Footnote Regional neighbours that backed South Sudan’s independence bid now primarily hope to prevent another collapse, but they have shown little interest in the peace deal since Machar returned to Juba and are now preoccupied with the crisis in Ethiopia, the lynchpin of the Horn.

South Sudanese across ethnic lines acknowledge that their country is troubled at its core. They describe deep and polarising ethnic divisions, both at the national and local levels, and a leadership class that has lost the people’s trust.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, Juba, Wau, Raja, Malakal, Tonga, Yei, 2018-2020.Hide Footnote Ideally, South Sudan would start over, taking seriously the profound frailty revealed by its rapid political implosion, while also confronting head-on the scale of new and renewed challenges created by the war, including deepened divisions and widespread destruction. A new roadmap must start with bolstering and widening the current ceasefires, and preparing for elections, but it must also look much farther ahead if South Sudan is to find a path toward a more durable political settlement.

Given the obstacles to resolving South Sudan’s core political problems, the government and its external partners are right to focus heavily on keeping the peace. Their immediate priorities are to maintain the ceasefire between the main belligerents Kiir and Machar and thus to prevent a return to wider war. To bolster the ceasefire, the authorities and civil actors, especially religious leaders, who frequently mediate peace at the grassroots, should also call for and develop local political settlements to calm down other hotspots and stop various conflicts from splintering into new disputes. Yet even if the ceasefire continues to hold, the Kiir-Machar relationship will be subject to centrifugal forces pulling the two of them apart. South Sudan will also likely see more raging local violence between ethnic groups and elite-backed militias. It could even face fresh rebellions.

A. Preventing Another Collapse

Keeping the peace between Kiir and Machar is the top short-term priority for the guarantors of South Sudan’s peace deal, although it will be no easy task given their bitter rivalry. Machar is the junior partner in the unity government and wields little actual power in Juba. Kiir maintains a firm grip upon the security services, who overshadow Machar’s appointees in local and state governments and can prise defectors out of the vice president’s camp, sowing continual discord. With both men continuing to command their own separate forces, the journey back to war could be short.

Keeping the peace between Kiir and Machar is the top short-term priority for the guarantors of South Sudan’s peace deal.

Divisions within Machar’s camp could also erupt into the open even before any wider falling-out between Kiir and Machar. The latter faces significant discontent with the peace deal among his own forces, since Kiir has yet to bring any of the vice president’s fighters into the national army despite agreeing to do so by mid-2019.[fn]The primary reason for the delays is Kiir’s hesitance to restructure the army or integrate tens of thousands of opposition forces. Kiir has claimed both that he lacks funds to unify the forces and that a UN arms embargo prevents him from importing the weapons needed to supply them. The Joint Defence Board, led jointly by a Kiir and a Machar appointee, says another main impediment is the need to harmonise military ranks across both sides, which would require numerous demotions. “Outcomes of CTSAMVM Technical Committee Meeting, 19 November 2020”, Ceasefire and Transitional Security Arrangements Monitoring Mechanism in South Sudan (CTSAMVM). Both sides admit to rampant rank inflation during the war as a means of recruiting fighters and preserving their loyalty. A senior security official for Machar tasked with restructuring his forces admitted that massive rank inflation on the opposition side would complicate unification. Crisis Group interview, 2019. See also Alan Boswell and Alex de Waal, “South Sudan: The Perils of Payroll Peace”, London School of Economics, March 2019; Craze, “The Politics of Numbers”, op. cit.; Flora McCrone, “Hollow Promises: The Risks of Military Integration in Western Equatoria”, Small Arms Survey, June 2020; and Boswell et al., “The Security Arena in South Sudan”.Hide Footnote Parts of Machar’s fractious coalition, which encompasses not just his own Nuer loyalists but many other aggrieved groups who fought the government during the civil war, could themselves take up arms again due to lost confidence in his ability to extract benefits for them in the unity government.[fn]Chief among such fears is that Nuer hardliners under Machar’s chief of staff, Simon Gatwec, and ethnic Shilluk “Agwelek” forces under General Johnson Olony could splinter together from Machar and return to war. Olony’s forces made clear they would return to war if the Shilluk do not regain territorial control of Malakal. Crisis Group interviews, Olony commanders, officials and supporters, Tonga, Juba, and remote correspondence, 2019-2020. Gatwec, a Lou Nuer from Jonglei state, who has formed a close tactical relationship with Olony along the South’s northernmost border with Sudan, has refused to come back to Juba and has publicly threatened to return to war. Crisis Group interviews, senior Machar officials and South Sudan analysts, 2020. For more on divisions within Machar’s camp, see Crisis Group Briefing, Déjà Vu: Preventing Another Collapse in South Sudan; and Crisis Group Report, Salvaging South Sudan’s Fragile Peace Deal, both op. cit.Hide Footnote In such a scenario, local conflicts could break out, and then snowball. These could spark splinter conflicts or culminate in the resumption of hostilities between Kiir and Machar as they blame each other for the renewed clashes.

Keeping the unity government together requires constant and concerted diplomatic pressure from the leaders of neighbouring countries, who have repeatedly stepped in at critical moments to push the two men to reluctant compromises. These leaders need to stay active in mediating to prevent the unity government from collapsing. But since many of them are now besieged by domestic problems, they may only rally to pressure Juba when they feel that the underlying Kiir-Machar truce is under dire threat.[fn]Khartoum and Kampala, the two main brokers of the 2018 accord, face their own challenges. President Yoweri Museveni has been focused on Uganda’s January 2021 elections, while Sudan is struggling internally with its ailing economy and political transition and in managing the fallout from conflict bordering Ethiopia. Faced with internal strife, Addis Ababa is unlikely to step back into a regional leadership role soon. Heated elections loom in Somalia, as in Kenya.Hide Footnote Other actors, including South Sudanese civil society actors, the UN and the African Union, will need to redouble their own efforts as well as prod regional heads of state to remain engaged.

B. Silencing the Other Guns

Keeping Kiir and Machar together, however, is no panacea for all the bloodletting in South Sudan’s many regions. Despite the ceasefire, violent deaths continue to spike across the country, including in the president’s strongholds, as other conflicts unfold. These require concerted efforts to achieve bespoke settlements.

The acrimonious dispute over Malakal, the capital of Upper Nile state and South Sudan’s second-largest city before the war but today mostly a ghost town, is top among local conflicts that could derail the national peace process.[fn]Olony rebelled against Juba before independence, largely due to his anger over boundary disputes. He had agreed to peace terms with Juba in mid-2013 but had not reintegrated into the South Sudan military when the December 2013 civil war broke out. At the start of the war, Juba heavily armed Olony, stationed in Malakal, against Machar’s forces. Amid escalating tensions with the government, the Agwelek rebelled in 2015 and shortly thereafter formally allied with Machar. Crisis Group analyst’s interviews in a previous capacity, Olony and other Shilluk representatives, Kodok, Malakal, Wau Shilluk, 2016. Olony commands fierce loyalty from his forces and many ethnic Shilluk, who see them as the chief defender of Shilluk rights and territory, although the Shilluk community has grown more divided in recent years. See also Joshua Craze, “Displaced and Immiserated: The Shilluk of Upper Nile in South Sudan’s Civil War, 2014-19”, Small Arms Survey, September 2019.Hide Footnote The conflict over the city predates South Sudan’s civil war and pits factions of Kiir’s Dinka against the ethnic Shilluk, whose Agwelek militia led by the powerful and popular General Johnson Olony joined Machar’s forces in 2015.[fn]Both Shilluk and local Dinka representatives express strident views, hardened by the conflict, about their respective territorial claims on Malakal. Crisis Group interviews, Malakal and Tonga, 2020. For more on the Malakal dispute, see Craze, “Displaced and Immiserated”, op. cit.; and Matthew F. Pritchard, “Fluid States and Rigid Boundaries on the East Bank of the White Nile in South Sudan”, European Institute of Peace, July 2020.Hide Footnote The Agwelek proved some of the strongest forces in Machar’s camp. But they operate with relative autonomy, making it clear that their primary interest lies in achieving control of Malakal. Olony’s officials and communal leaders in Olony-controlled territory threaten renewed insurgency unless his forces are able to re-enter the city.[fn]The primary threat the Malakal dispute poses to the wider national ceasefire is that a splinter alliance could form between Olony and Gatwec. See fn 36 above.Hide Footnote

The battle for the governor’s seat in Upper Nile state severely frayed ties between Machar and Olony, straining their alliance and possibly setting the stage for renewed fighting. Under the peace deal’s terms, Machar had won the right to appoint Upper Nile’s governor, seated in Malakal. He nominated Olony in June 2020, but Kiir refused to appoint him.[fn]Kiir demanded to meet Olony first in Juba, with his spokesman labelling Olony a “warmonger”. Olony, in response, refused to travel to Juba unless Kiir appointed him governor first. “Kiir rejects Machar’s nominee for Upper Nile governor”, Radio Tamazuj, 2 July 2020. In January 2021, Machar finally urged Olony to come to Juba or nominate someone in his stead, which Olony pointedly refused to do. “Subject: Respond (sic) to your request for replacement of Lt. Gen. Johnson Olony Thubo as a nominee for Upper Nile State Governor”, official letter from Olony to Machar, 22 January 2021, copy on file with Crisis Group. Olony said his military and political leadership rejected replacing his nomination. Olony committed to coming to Juba after being appointed governor.Hide Footnote For months, neither side budged, holding up the formation of state governments across the country. Machar finally ended the impasse in January 2021 by bypassing Olony and nominating the latter’s former deputy. Kiir then quickly confirmed the appointment. Olony’s spokesman rejected the move, however, with his loyalists claiming betrayal by Machar.[fn]Statement by Agwelek spokesman Morris Samuel Orach, 30 January 2021, copy on file with Crisis Group. Crisis Group interviews, senior Agwelek officials loyal to Olony, January-February 2021.Hide Footnote The rift between Machar and Olony could lead to violence between supporters of both men, which would require diplomatic intervention from regional countries, particularly Sudan, to cool down.[fn]Olony and other allied Nuer generals are based in Magenis, on South Sudan’s northernmost border with Sudan, and regularly transit through Sudan, including Khartoum. Khartoum has previously backed Olony during earlier armed struggles, at times as a proxy force against the neighbouring SPLM/A-North forces under Abdulaziz al-Hilu in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan’s Southern Kordofan. Crisis Group interviews and Crisis Group analyst’s interviews in a previous capacity, 2016-2021.Hide Footnote Those who could side with Olony include Nuer generals who have also fallen out with Machar and who denounce his agreeing to join the unity government when so much of the peace deal was not implemented.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, senior Agwelek officials and discontent Machar officials, 2019-2021.Hide Footnote

Other local conflicts also require attention. Disputes over the north-western city of Wau sparked a brutal conflict in Western Bahr el Ghazal, a state in South Sudan’s north west, after the first peace deal collapsed in 2016.[fn]The conflict primarily pitted ethnic Fertit, who compose most of Western Bahr el Ghazal’s population, against the government over grievances related to central government neglect and control of Wau, the state capital and once one of the South’s three provincial capitals. Crisis Group interviews, Wau, 2019 and 2020; Raja, 2020.Hide Footnote Machar’s home Unity state has also remained stuck in internal conflict, linked to wider power politics, since the 1990s. There, scorched-earth combat and systematic looting has displaced hundreds of thousands and eviscerated their livelihoods since 2014.[fn]The conflict in Unity state primarily pits Nuer sections of southern Unity, mostly loyal to Machar, against the Bul Nuer of northern Unity, aligned with Kiir. Unity is also home to Vice President Taban Deng Gai, who was one of Machar’s top officials before defecting to Kiir in 2016, and who also maintains forces in the state.Hide Footnote In Jonglei, in the country’s east, alarming and escalating intercommunal fighting erupted in 2020.[fn]Jonglei descended into cycles of recriminatory attacks in 2020, killing hundreds, or possibly thousands. The conflict primarily pitted ethnic Murle against both neighbouring ethnic Dinka and neighbouring ethnic Nuer. Different elites in Kiir’s camp quietly backed opposing Dinka and Murle fighters, while many of the ethnic Nuer fall within Machar-controlled territory.Hide Footnote Intra-Dinka fighting in Warrap and Lakes states has also reached fever pitch, with hundreds killed each year and local militias so well armed they can go toe to toe with the military. National and local officials, together with local civil society actors including religious leaders, will need to keep pushing to resolve all these conflicts, supported by the UN peacekeeping mission.

A rebellion in the southern state of Equatoria is yet another challenge. The region is home to the most active conflict and the clearest carryover from the civil war. Insurgents under the National Salvation Front banner led by Thomas Cirillo, a former SPLM general who rose to deputy army chief before defecting, operate throughout much of the central and western Equatorian countryside, demanding greater local rights and complaining of widespread abuses by government security forces they now deride as tribal militias.[fn]See any of several National Salvation Front press statements since 2017.Hide Footnote Cirillo signed a January 2020 ceasefire, called the Rome Declaration and separate from the Kiir-Machar deal, but heavy fighting began again in April, as large-scale government offensives met with guerrilla warfare. After talks reconvened in October, the parties recommitted to a short-term ceasefire as they deliberate over a ten-point declaration of principles to frame their discussions.[fn]Draft ten-point Declaration of Principles, copy on file with Crisis Group. The parties agreed upon seven of the ten points but are still negotiating over the other three.Hide Footnote

Ending the Equatoria conflict will also not be quick or easy.

Ending the Equatoria conflict will also not be quick or easy. Given that Cirillo’s chief aim is a heavily devolved federal structure, he is unlikely to accept a power-sharing post in the national government as sole prize for making peace. Nor is that blandishment likely to mollify his supporters. Mediators in Rome, belonging to Sant’ Egidio, a lay Catholic community, should draw Cirillo into the national ceasefire process, as agreed in 2020, and push for credible talks to address core Equatorian grievances.[fn]“Declaration on Recommitment to CoHA, the Rome Declaration and the Rome Resolution”, 11 October 2020, copy on file with Crisis Group.Hide Footnote Negotiations should aim to reach an agreement on strengthened constitutional review to negotiate the state’s structure (explored further below) and a separate initiative to address longstanding Equatorian complaints, such as the abusive incursions of armed Dinka cattle herders from neighbouring states.

Amid all the violence in South Sudan, its leaders and people must also prepare for elections, scheduled for 2022 or later. For now, there is little clarity about when the vote will take place. South Sudanese and external actors will need to manage a delicate and combustible pre-election period, taking care neither to rush the country into a vote, if elections look likely to trigger major conflict, nor to let the process stall indefinitely and thus create renewed flashpoints between the incumbent president and an embittered opposition.[fn]African diplomats are more likely to stress concerns about a rush to elections. “If we jump the gun and talk about elections now, we might be self-defeating”, said an African Union official, stressing the need first for “an environment conducive for democracy”. Western donors mostly say they struggle to look that far ahead. “We haven’t talked about elections yet in South Sudan because it is so far away. So many issues, transitional justice, financial reforms, to focus on first”, said a European Union official. “People struggle to have headspace to deal with [elections] at the moment. Also, the question throws up a huge number of difficulties”, said a senior Western diplomat in Juba. According to a senior U.S. official, Washington is focused on pressing South Sudan to stick to its election commitment, while hoping that the pool of presidential contenders expands beyond Kiir and Machar. One UK official noted worries – “the elections just look like a massive time bomb” – but said in-depth discussions on mitigating the risk had yet to start. Crisis Group interviews, Western and African officials, Juba, Washington, Brussels, London, undisclosed African location, 2020.Hide Footnote If election preparations do proceed, the country’s external partners will need to work to mitigate tensions as they crop up and also ensure that violence in the Equatoria region – where a rebellion against the state is now in play – is brought to peaceful resolution so elections can take place there. They may also have to facilitate a pre-election dialogue between Kiir and Machar, to avoid their relapse into conflict in the likely event that they run against each other in the elections.

A. Risks Inherent in an Election

The first election-related dilemma relates to timing. Already, the calendar is shaping up to be contentious. Some South Sudanese advocate that the polls take place either three years from May 2019, when the peace deal’s signatories were supposed to form a unity government, or three years from 2020, when the parties actually did so. Others, given the lag in filling many unity government positions, including formation of a new national legislature and state and local governments, suggest that the three-year countdown start only after the unity government is fully installed. Just getting an agreement on an election date could become a pretext for dangerous brinkmanship. For now, Kiir and Machar have yet to take a strong position as to when precisely the polls should occur, though some officials close to Kiir have voiced support for a longer timeline.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, Kiir allies and Machar allies, 2019-2020.Hide Footnote

Diplomats in South Sudan will have to strike a balance between pushing for elections without jeopardising the country’s stability.

Diplomats in South Sudan will have to strike a balance between pushing for elections without jeopardising the country’s stability. Ethnic tensions are sky-high after years of bloodletting, and given how tortuous political processes tend to be in South Sudan, it is likely that the run-up to elections will be littered with disagreements that will slow down preparations and require constant unsticking. Holding elections if logistics have not been adequately prepared, or if broader tensions linked to the elections themselves are still rife, could be risky.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, 2020.Hide Footnote In those scenarios, a unilateral rush to polls by Kiir that does not give his opponents time to prepare would provoke them to cry foul: they would likely label the election a sham.

The difficulty of shepherding the parties to a mutually acceptable poll is not lost on South Sudan’s external partners. Some diplomats say the unity government must hold elections earlier rather than later. They fear that failure to do so may tempt it to delay the polls indefinitely, illegitimately extend its term and deny people a chance to choose their leaders as promised in the peace accord.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, Juba and Nairobi, 2019-2020. Ugandan President Museveni has also frequently urged swift elections to resolve the political disputes in South Sudan.Hide Footnote Conversely, others fear that if South Sudan is rushed into holding an election when politicians are still disputing the vote’s management and preparation, more violence would result. “We really need those full three years”, says a top Western diplomat.[fn]Crisis Group remote interview, Juba, 2020. The sheer difficulty of organising and financing a vote in South Sudan could mean further postponements, especially if deadline extensions push the election into the rainy season, when much of the country is inaccessible by road. Crisis Group interview, senior UN official, Juba, 2020.Hide Footnote Other observers say even more time might be required. That said, indefinite delays could also provoke hostilities if the opposition perceives them as ploys allowing Kiir to cling to power.

South Sudan’s partners should not fixate on deadlines at the expense of politics. In this regard, Crisis Group’s advice mirrors that in late 2019 against pushing Kiir and Machar to form a government by a November deadline, given that Machar was not yet ready to return to Juba and renewed war loomed as a distinct possibility as a result.[fn]See Crisis Group Briefing, Déjà Vu: Preventing Another Collapse in South Sudan, op. cit.Hide Footnote With a bit more time, the parties succeeded in forming a unity government in February 2020, following last-minute concessions by both Kiir and Machar.[fn]See Crisis Group Statement, “A Major Step Toward Ending South Sudan’s Civil War”, 25 February 2020.Hide Footnote If rushing elections risks unleashing more instability, external partners should support a delay in the polls to mitigate those political tensions. African leaders, donors and South Sudan’s other bilateral partners should avoid sanctifying a possible sham election, should Kiir appear to be staging one, for instance by rushing to hold polls without adequate preparation. Such a vote would only further anger opposition actors and reignite ethnic animosity across the country.

Even if the parties can reach consensus on timing, persistent diplomacy will be essential to help the country navigate a path to elections strewn with obstacles. Should either Kiir or Machar unexpectedly step aside, or be unable to run, new contenders could jostle to replace them, possibly violently, and upend national politics while imperilling any scheduled election. Machar’s coalition could fracture further, again possibly violently, including if he feels politically checkmated and strikes a deal with Kiir to run again as his vice president, as some of his supporters fear.[fn]Unlikely as a Kiir-Machar ticket may seem, Machar previously did much the same: splitting from the SPLM in 1991 and waging years of internecine war, only to reunite with it much weakened in 2002. Machar ran as Kiir’s vice president in the 2010 elections.Hide Footnote Then there is the south of the country, where Cirillo’s rebellion rages. If elections cannot happen in southern areas due to insecurity, Equatorians may consider their voices stifled and feel more disillusioned. South Sudanese, regional leaders and other diplomatic partners of Juba should focus on bolstering political inclusion before the vote, by fulfilling the peace deal’s terms and bringing in Cirillo’s group, to further enable a secure environment for the vote to take place, including in Equatoria.

B. Averting the Loser-Loses-All Scenario

If Kiir and Machar do both contest elections, which is the most likely scenario, a post-electoral crisis could easily erupt.[fn]Violence could also erupt in many places over accusations of poll rigging, as occurred after the 2010 elections. These local uprisings eventually coalesced into a rebel coalition that received material backing from Khartoum. See “Pendulum Swings: The Rise and Fall of Insurgent Militias in South Sudan”, Human Security Baseline Assessment for Sudan and South Sudan, November 2013.Hide Footnote Both men tend to couch their political rivalry in zero-sum terms. Violence could occur out of frustration on the part of politicians and their followers who feel that the result has locked them out of state power and a share of its resources. In this scenario, aggrieved parties would perceive their rivals as having used the vote to impose a final victory in the war. Kiir’s allies, in particular, make no secret of the fact that they view the elections as a means of crushing Machar.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, government officials, Kiir allies and South Sudanese analysts, Juba and Nairobi, 2018-2020.Hide Footnote Machar, meanwhile, sees the polls as his last chance to defeat the long-dominant Dinka elite and thus hold together his coalition, which expects nothing less from him than utter triumph.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, Machar allies and supporters, 2018-2020.Hide Footnote

If Kiir and Machar do both contest elections, which is the most likely scenario, a post-electoral crisis could easily erupt.

Incentives for post-election violence will be acute. South Sudan’s highly centralised power structure and political economy raise the election’s stakes, since there are limited consolation prizes, especially if Kiir continues to flout the constitution by refusing to devolve oil revenues and removing powerful governors by decree.[fn]“South Sudan’s Constitution of 2011”, Constitute Project, August 2019. The September 2018 peace deal also acknowledges the popular demand for federalism and devolution: “Cognizant that a federal system of government is a popular demand of the people of the Republic of South Sudan and the need for the Revitalised Transitional Government of National Unity to reflect this demand by way of devolution of more powers and resources to lower levels of government”. “Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS)”, IGAD, September 2018.Hide Footnote South Sudanese elites have often used violence to negotiate their way into a greater share of power. Even in a much less polarised ethno-political environment, disputes about the 2010 elections produced several local rebellions.[fn]See “Pendulum Swings: The Rise and Fall of Insurgent Militias in South Sudan”, op. cit.Hide Footnote Political divisions are sharper and deadlier today.

If a Kiir-Machar election showdown does indeed take shape, regional leaders who serve as guarantors of the peace deal should try, by brokering pre-election dialogue, to extract assurances for losing parties so as to lower the stakes. One option would be to guarantee, in advance, another broad-based unity government. The parties could, for instance, designate slots in the future government, including vice presidential positions, that would go to losing parties according to vote share. Such pre-election guarantees are unusual and would likely require continued diplomacy from regional leaders to enforce. But they have at least one precedent in East Africa.[fn]In Zanzibar, where elections often end in violent contestation, a 2010 “reconciliation agreement”, then enacted into law through a referendum, gave the runner-up the power to nominate a vice president while requiring the president to appoint several ministers from that party to a national unity government, paving the way for peaceful elections in 2010 and 2015. Ahead of 2019 polls, Crisis Group warned the ruling party not to amend the law to permit the winning party to form a unity government with any parliamentary party of its choosing, rather than the second-place finisher. Crisis Group argued that this change would undercut the power sharing at the heart of the 2010 agreement. See Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°144, Averting Violence in Zanzibar’s Knife-edge Election, 11 June 2019.Hide Footnote Kiir is unlikely to welcome such guarantees, but they could be critical for preventing a return to conflict.

Other African leaders and major donors, including the U.S. and the European Union, should encourage IGAD and South Sudan’s leaders to seriously engage in forging such a settlement. Such a deal would serve to bolster, rather than dissolve, the basic political settlement that undergirds the 2018 peace deal in South Sudan, which is that peace is possible only if the major groups feel included in the country’s all-important political centre. The deal would, in some ways, preserve a troubling and unstable status quo. But the likely alternative is not transformational change, but a return to war.

Barring unforeseen events, the elections will likely usher either Kiir, Machar or both back into power, hardly a reason for celebration given their records in office. Many South Sudanese are desperate for change, a sentiment widely shared in the outside world.[fn]Other regional and African elites are embarrassed by the repeated bloodshed in South Sudan at a time when Africa has vowed to “silence its guns”. Crisis Group interviews, African officials, Nairobi and Addis Ababa, 2018-2020.Hide Footnote Both men are unpopular even among their own constituencies.[fn]Crisis Group interviews and Crisis Group analyst’s interviews in a previous capacity, Kiir and Machar allies, aides and supporters, many locations across South Sudan in both Kiir- and Machar-held territory, 2016-2020.Hide Footnote Most of Kiir’s ethnic group, the Dinka, view his presidency as disastrous – and more and more of them are willing to say so publicly, including during the recently concluded National Dialogue Kiir himself inaugurated.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, Dinka officials and intellectuals, Juba and Nairobi, 2018-2020; Crisis Group analyst’s interviews in a previous capacity, Aweil, Rumbek, Yirol, 2017. On the widespread calls during the National Dialogue for both Kiir and Machar to step aside, see “Covering Note to the National Dialogue Reports”, Office of the Co-chairs of the National Dialogue Steering Committee, n.d., copy on file with Crisis Group. In January 2021, leading members of the Jieng (Dinka) Council of Elders, a controversial Dinka nationalist lobby group previously influential with Kiir, also publicly supported the call by the National Dialogue co-chairs for Kiir and Machar to step aside. “Breaking the Silence”, press statement, Jieng Council of Elders, 26 January 2021.Hide Footnote Many Nuer are deeply critical of Machar, whom they perceive as narrowly self-interested. This sentiment has only grown as Machar has appointed family members and inexperienced sycophants to top positions in the unity government.[fn]Crisis Group interviews, senior officials in Machar’s camp, Juba and remote, 2020. This discontent is widespread but especially high among the hardline Nuer commanders who never trusted Machar’s leadership. See “A Fractious Rebellion: Inside the SPLM-IO”, Small Arms Survey, September 2015. Although there is no clear contender to replace Machar as the main opposition leader, his coalition has also suffered, as he has lost defectors from other minority ethnicities, including the Fertit in Western Bahr el Ghazal and groups in Equatoria, to Cirillo’s National Salvation Front on one end and the government on the other. Nearly all non-Nuer in Machar’s camp complain of Nuer dominance. Crisis Group interviews, 2018-2020.Hide Footnote Both men are likely to stay in power, however, as their supporters remain united against each other and as each works to keep alternative figures from his camp from emerging.[fn]Both Kiir and Machar are political survivors. There is no clear route in either camp to a leadership challenge at present. The jockeying over succession is fierce but silent in Kiir’s camp, meaning that the president will likely have to coronate an heir or design a succession process should he ever step aside. On Machar’s side, meanwhile, there is no one who can clearly both unite a Nuer base and lead a coalition that draws significant support from other aggrieved minorities. Both sides are keen to avoid a debilitating internal power struggle, since both are united primarily by opposition to the other, largely on ethnic grounds. Ibid.Hide Footnote

Even if both men, by some extraordinary turn of events, departed South Sudan’s political scene, the country would still be bitterly divided, awash in guns, lacking state institutions and infrastructure, and in need of broad consensus to avoid rampant bloodshed. Any long-term strategy for remaking the country must address the fragility at the heart of its politics. Blaming the mess on Kiir and Machar alone, or on their generation, has, understandably, become common in diplomatic circles but can underplay the destructive tendencies in South Sudan’s political system that helped drive the country to ruin. Kiir himself appears to acknowledge the controversy surrounding that system, and places himself at the centre of a tug of war between hardliners and advocates of inclusion. Speaking at the conclusion of his National Dialogue initiative in November, Kiir addressed his critics:

On the charge [that] liberators’ monopoly of power is the cause of our problems, there is another view from those who fought in the war that what is affecting this country is excessive political inclusion. … You can see what we have been doing all along is the balancing act between these two positions.[fn]Kiir speech at the close of the South Sudan National Dialogue Conference, Juba, 17 November 2020.Hide Footnote

In reality, Kiir’s argument is misleading: conflict arises in South Sudan when entire ethnic groups or regions feel excluded from power and oppressed by those who wield it. Moreover, Kiir’s attempts at “inclusion” – ad hoc buyouts of elites rather than deeper reforms – fall short. Indeed, the system itself in South Sudan acts as a disincentive for elites to build inclusive coalitions. Ideally South Sudanese would rework the system, looking for whatever safeguards can be found to lessen the risk of exclusionary politics that is likely to lead to political violence. Even if the root and branch changes necessary seem a remote prospect for now, supporters of reform inside the country and their international allies should, in other words, tug unapologetically on the inclusion side of the rope whenever the opportunity arises, both to mitigate immediate conflicts and to prevent future recurrences.

A. Sharing the Centre

One way to reduce the pernicious effects of exclusionary politics is to build a system where power can be shared more equitably at the centre. South Sudan can look elsewhere for guidance, though each example it draws from comes with caveats.

One way to reduce the pernicious effects of exclusionary politics is to build a system where power can be shared more equitably at the centre.

A rotational presidency might hold some benefit. Nigeria, for example, rotates the presidency by informal convention between the country’s northern and southern regions, in an attempt to keep all invested in the political order, though the system certainly does not resolve the country’s myriad conflicts related to power, money and disputed elections or address popular anger at elites themselves.[fn]See Anthony Akinola, “The Concept of a Rotational Presidency in Nigeria”, The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs, vol. 85 (1996).Hide Footnote In Tanzania, elites have crafted a similar power-sharing arrangement that rotates the presidency between a Christian and a Muslim every ten years, though this arrangement has done little to prevent the country’s turn toward authoritarianism.[fn]This arrangement has held since founding President Julius Nyerere’s retirement in 1985.Hide Footnote In light of its own extreme fragility, South Sudan could adopt a similar rotational policy. It might not solve all South Sudan’s problems, but it could encourage multi-ethnic alliances or mean losers of elections feel they have a shot at the presidency next time around.