King Ludwig II of Bavaria, often called the “Mad King,” was known for extravagance. Portrait by English painter Gabriel Schachinger, 1887.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

King Ludwig II of Bavaria, age 18 when he assumed the throne in 1864, was from a family richly endowed with psychotic illness. He became increasingly grandiose, arrogant, and unpredictable in his dealings with his cabinet as he requested enormous funds for building and furnishing vast castles, including the magnificent Neuschwanstein, the model Walt Disney used for his theme parks.

A commission of four psychiatrists, including Dr. Gudden, a professor of psychiatry and one of the early proponents of “no-restraint,” established that Ludwig had “primary insanity” and needed to be removed from office. Initially, the king’s soldiers remained loyal and tended to “overlook” the seriousness of his illness. But when they learned of Ludwig’s sadistic, “preposterous” orders to torture the members of the commission, they became convinced.

The plan was to transport Ludwig to one of his castles, Castle Berg, and create a “one-person mental hospital.” Dr. Gudden would accompany the entourage. Ludwig, prone to suicidal outbursts, seemed calmer once there. Together, Dr. Gudden and Ludwig walked around the castle grounds, which included a scenic path around Lake Starnberg. Suddenly, Ludwig ran toward the lake, and Dr. Gudden ran after him. At least by one historical account, a struggle ensued; Ludwig hit him and held Gudden’s head underwater until he drowned. Ludwig continued farther into the lake until he drowned. He was 40 years old (Alexander, 1954).

The body of King Ludwig II, drowned in a lake with his psychiatrist. 19th century, unknown artist.

Source: Credit: Private Collection, copyright Giancarlo Costa/Bridgeman Images. Used with permission.

This vignette, albeit an extreme example, poignantly highlights certain difficulties of treating a V.I.P.—initial denial and minimizing the seriousness of symptoms by those around him, making exceptions to standard care that would have involved admission to a proper psychiatric hospital, and then implementing a poorly improvised treatment plan that led to disaster—in this case, not only the murder of his psychiatrist but the suicide of the patient.

The first usage of the term V.I.P., according to the Oxford English Dictionary, occurred in the 1930s—a “very important personage.” Weintraub (1964) was the first to use the designation in healthcare and described 12 patients, including influential people and professional colleagues, admitted to a psychiatric hospital who exerted “undue pressure on the staff.” He called this the V.I.P. Syndrome.

In either a medical or psychiatric context, a V.I.P. is anyone “by virtue of fame, position, or claim on the public who may substantially disrupt the normal course of patient care” (Smith and Shesser, 1988) and influence a clinician’s judgment or behavior (Alfandre et al., 2016).

Weintraub noted that the “variety of ‘special treatment’ sought by the V.I.P. is infinite,” including circumventing usual admission procedures, refusing to accept the patient role, requesting a private room, or insisting on being seen by the most senior physician. Significantly, of his patient sample, ten were “complete therapeutic failures,” a not-uncommon result.

“Fame,” by Italian artist Luca Cambiaso, mid-to-late 16th century.

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC. Robert Lehman Collection, 1975. Public Domain.

These “special patients” often suffer from their specialness (Feuer and Karasu, 1978), and paradoxically, rather than getting better treatment, their V.I.P. status may compromise it (Silverman et al., 2012) and lead to inferior, substandard care.

For example, clinicians may fail to obtain a complete history for fear of offending a V.I.P. by asking personal questions (Gershengoren, 2016) or fail to do a complete physical or request invasive but necessary diagnostic tests for fear of inconveniencing or causing discomfort (Frenklach and Reicherter, 2015). Conversely, they may be unnecessarily overzealous in their work-up for fear of missing a diagnosis (Groves et al., 2002).

Patients can be well-known, such as celebrities, benefactors, or CEOs, or well-connected, such as family members or medical colleagues. The “I” in V.I.P. can stand for “influential” (Schenkenberg et al., 2007) or even “intimidating” (Rockwell et al., 2022). Notably, the designation as a V.I.P. is context-dependent—a V.I.P. in one setting may be unknown or unimportant in another (Geiderman et al., 2018).

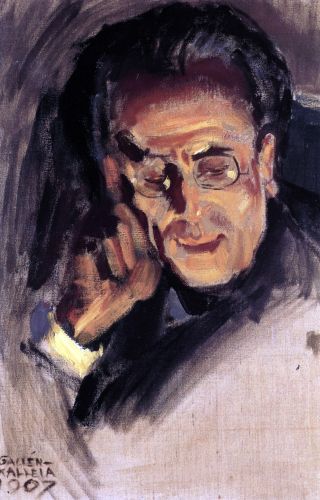

Portrait of musical composer Gustav Mahler, 1907, by Finnish artist A.V. Gallen-Kallela. by

Source: Photo copyright Fine Art Images/Bridgeman Images. Used with permission.

Few are immune, though, to the impact of a world-renowned celebrity, which often generates awe in others (Gershengoren; Groves, et al.), i.e., a starstruck phenomenon (Feuer and Karasu).

Ernest Jones, Freud’s primary biographer, writes that Freud, loathe to interrupt his summer vacation, could not refuse to see the famous composer Gustav Mahler, who requested an emergency consultation (Jones, 1967).

Should V.I.P.s be treated differently? Some would argue that this is unethical, that all patients deserve to be treated specially (Geiderman et al.), and that it can be “disorienting” to a healthcare system when V.I.P.s receive unusual attention (Alfandre et al.).

For example, treatment of a V.I.P. should never take priority or jeopardize the care of another patient, particularly one who is not stable or in a life-threatening condition (Geiderman et al.).

Rather than necessarily requiring special privileges, a V.I.P. requires a special understanding of his or her specific circumstances (Feuer and Karasu). Guzman et al., (2011) delineate nine principles, including teamwork, protecting the patient’s security, and maintaining communication among those caring for the V.I.P.

In particular, “The single most important nonclinical issue is information management,” including titrating the “public’s right to know,” especially when it involves political figures with issues of their right to privacy (Groves et al.).

“The Triumph of Fame,” Netherlandish, probably Brussels, ca. 1502-4. Based on a poem by Petrarch.

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase, The Annenberg Foundation Gift, 1998. Public Domain.

“Misinformation is even more likely to occur when the illness includes some question of mental functioning” in those with political power, as was the case with Woodrow Wilson and Ronald Reagan (Kucharski, 1984)—and King Ludwig II. This concern has existed throughout history and continues as the public rightly questions the mental and physical capacity of its leaders.

Source link : https://www.psychologytoday.com/za/blog/the-gravity-of-weight/202410/treating-the-vip-patient-without-being-starstruck

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-06 18:04:56

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.