Last week the Mauritian government and opposition parties snubbed an invitation from the Russian government to attend a meeting of African parliamentarians in Moscow. Diplomatically, Port-Louis seems to be taking a harder line against Russia than either India or many African states, which have traditionally moored Mauritian foreign policy. So why is Mauritius looking more hawkish on the Russian-Ukrainian war?

Moscow calling

Last week the opposition parties as well as the government snubbed an invitation from Moscow to attend a conference for African parliamentarians between 19-20 March. The event itself was billed by Russian President Vladimir Putin as a forerunner to the second-ever Russia-Africa summit to be held in St. Petersburg in July, the first one held in Sochi back in 2019. The refusal of Mauritian politicians to go to Moscow highlights just how hard-line Mauritian politics has become against Russia as a result of its war in Ukraine that broke out in 2022.

The roots of this conflict date back to the late 1990s when the US-led NATO decided to expand eastwards to absorb formerly Communist members of the Warsaw Pact that broke away from Moscow. At the time, George F. Kennan – architect of America’s containment strategy against the Soviet Union during the Cold War – warned that NATO expansion into Central and Eastern Europe would be “the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-Cold war era” as it contradicted assurances given by Washington D.C to Mikhail Gorbachev, last head of the USSR, that NATO would not expand eastwards in return for Gorbachev’s acceptance of a reunified Germany.

A year before Kennan’s warning, Russian President Boris Yeltsin too warned against NATO’s expansion calling it “a mistake and a serious one at that”. Yeltsin demanded a guarantee that no former Soviet republics would be brought into NATO. What happened instead was a steady eastwards march with NATO bringing in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic in 1999; then in 2004 it spread further to include Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. At a 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest, Georgia and Ukraine were identified as future members, enraging Moscow. A brief war ensued between Russia and Georgia centred on pro-Moscow breakaway bits of Georgia. But NATO’s expansion continued apace: in 2009 Albania and Croatia, and then in 2020 Montenegro and North Macedonia were brought in.

The Ukrainian situation came to the boil in 2014 when protests toppled Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych – who got most of its support in the pro-Russian east of the country, sparking off a civil war that ended up with the Russian annexation of Crimea. Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in 2014 warned against treating the war as a proxy fight against Moscow, “To treat Ukraine as part of an East-West confrontation would scuttle for decades any prospect to bring Russia and the West – especially Russia and Europe – into a cooperative international system.” In 2022, both Russia and Ukraine entered into a full-blooded war. “This fight is probably both about NATO expansion, of which there was concern but also about Putin having a grander vision of historical Russia,” says Milan Meetarbhan, formerly Mauritius’ top diplomat at the UN, “just last week we had the 20th anniversary of the US’ invasion of Iraq which was justified as getting rid of weapons of mass destruction which turned out to be a pretext. When superpowers act, there is usually more to it than what they publicly say.”

Mauritius has gone beyond India and major African states in condemning Russia at the UN for its invasion of Ukraine.

More hawkish?

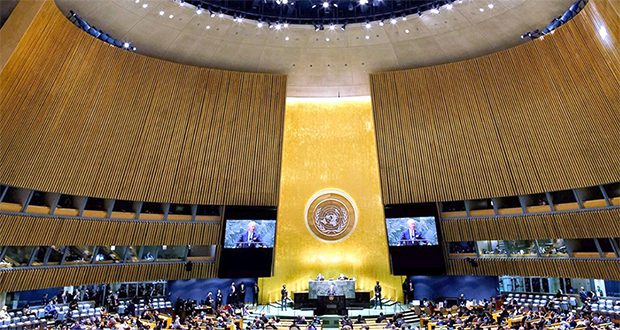

When it comes to the current war in Ukraine, Mauritius seems to have broken from two of its most influential polestars in formulating its foreign policy: New Delhi and the African states. India, for example, has refrained from criticizing Moscow, which has traditionally been a major weapons and oil supplier. A recently concluded G20 summit hosted by India failed to come up with an agreement on Ukraine. But New Delhi is not just constrained by business and a soft spot for its old Cold War ally, it’s also constrained by public opinion. A poll by the University of Oxford released in February this year found that 54 per cent of the Indian public wanted the war to end now, even if it means Ukraine handing over territory. In Africa too, where Western states have so often been on the wrong side of history, feelings against Moscow don’t run too deep. “This is not about ideologies or systems of government,” says Meetarbhan, “this is about history. When many of these states were struggling against colonialism, apartheid and the Portuguese empire in Africa, the Soviet Union supported many of these movements.” Examples include funding and paramilitary training to the ANC in South Africa, ZANU-PF in Zimbabwe, and the MPLA in Angola. Africa is a major wheat importer, bringing in 47 million tonnes in 2019 and is expected to rely on imports for over 63 per cent of its wheat by 2025. At the recent meet in Moscow, Putin pledged to bring in 12 million tonnes of wheat into Africa free, should a Turkish-brokered agreement for the use of Black Sea ports not be renewed. This reticence to criticise Moscow has been seen at the UN: a UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolution in March 2022 saw 35 countries abstaining – 17 of them being African at another UNGA vote in February this year demanding that Moscow withdraw its troops from Ukraine, 32 countries abstained – 15 of them African. “On this particular issue we could not align behind Africa because there was no group position, Africa itself is divided on this,” explains Meetarbhan. Unlike either India or Africa, Mauritius has taken a more hawkish position, consistently voting against Russia when it comes to Ukraine at the UN. Back in April 2022, Port-Louis voted in favour of suspending Russia from the UN’s Human Rights Council – despite the fact that only nine other African states supported the resolution. Similarly for UNGA resolutions such as the one in October 2022 condemning Russia’s annexation of breakaway territories of Ukraine.

The difference this time

It’s not just that Mauritius has gone further diplomatically than India or the major African states, but also much further than Mauritius itself had gone in its stance over the brief 12-day war between Russia and Georgia in 2008. During the lead-up to that conflict, Port Louis abstained from any UN resolutions directed against Russia (such as one in May 2008) and when war broke out it did not have any position on the war itself: it was just too remote a war to risk taking any position. Particularly as during that time Mauritius was looking to woo more Russian tourists by allowing flights of the Russian airline Transaero in March 2007.

So why has Mauritius gone from muted during the 2008 Russian-Georgian war to hawkish on the Russian-Ukrainian one in 2022? The first reason is that unlike the remote 2008 war in Georgia that did not affect Mauritius much, the war in Ukraine does. “We had to take a firmer stand because Ukraine is much more strategic than Georgia was. What do we get from Georgia? But the reality is that what happens in Ukraine is being felt in Africa and in Mauritius” says Arvin Boolell, former foreign minister.

According to economist Pierre Dinan, the Ukrainian war has come as a jolt to the WTO trading regime that replaced GATT in 1995, “the basic principle has been that goods and services should be produced where they are cheapest. The war is not allowing that to happen. It was only later that we realized how big of a wheat producer Ukraine really was” he says, “now with sanctions and problems with trade and shipping, that were already suffering since Covid-19, we now see the effects of raised costs and inflation. And we are at the receiving end in Mauritius. We cannot rely on distant countries for our food.” The effect of the war on shipping even extends to products Mauritius is supposed to be self-reliant on, such as poultry: “all of their feed comes from maize imported from Australia and Brazil. Shipping disruptions affect that too. Why can’t we produce their feed from maize grown in Mauritius or in Madagascar that could be our breadbasket?”, asks Dinan.

This is not to say that all the problems are down to the war in Ukraine: “Such spikes are usually shortlived. If there is a fear about an interruption of supply of a basic commodity, then speculators, investors and hedge funds move in to take advantage of higher prices,” explains Megh Pillay, former director general of the StateTrading Corporation, “but then prices stabilise because others who had been dragging their feet then bring more of that commodity on the market and prices eventually stabilize. For food it could be as soon as three or four months. Global markets correct themselves quite quickly.” He points to global oil prices which have been going down of late due to a combination of India and China continuing to buy Russian oil and bank failures in the West sparking fears of another 2008 global financial crisis. “The problem is shipping and supply chain disruptions that date back to Covid and also the fact that our procurement process plays against prices going down,” says Pillay, “we buy our basic commodities in bulk on a nationwide basis so we cannot take advantage of price decreases in a dynamic market and the STC has to go through a tendering process and evaluate bids which takes time, so there is always a lead-time between global prices going down before it is reflected in the Mauritian market. A public sector company just cannot react spontaneously to changes in prices on the global market the way a private company can.”

The second reason is the Chagos islands. For the first time in its diplomatic history, Mauritius is leaning heavily on international law and the UN to pressure the UK to reach a deal on handing back the islands. “If we are arguing for the application of international law on the Chagos, and if the war in Ukraine constitutes a breach of international law, we cannot argue for the law in one case while condoning an invasion of a sovereign country in another,” argues Meetarbhan. Mauritius is also hoping to reach a deal with the US to keep the base on Diego Garcia and is keen to project itself as a reliable partner in the region. Resolving the Diego issue could also, Port-Louis hopes, unlock a long moribund bilateral trade deal with the US – kept in abeyance over the status of the Chagos – guaranteeing access to the US market for Mauritian exports rather than constantly relying on AGOA whose future is uncertain.

And this leads to the third reason why Mauritius has reacted differently this time round: economics. “After independence we had no choice but to be pro-Western and pro-US because democracy, market access to Europe and the presence of the US on Diego Garcia made Mauritius much more comfortable with the West,” says Boolell – unlike major states in Africa, Mauritius traditionally did not see the Soviets as a benign sponsor of liberation movements but rather as a perennial threat to its own political stability – “nothing much has changed since then.”

Europe and the US are still the main markets for Mauritian exports and tourists and the main way for Mauritius to keep its financial sector off EU and IMF blacklists. In contrast, Russia is neither a major tourist market and trade with Moscow was a paltry $2.6 million in 2019. Mauritius can afford to alienate Moscow, but not the West. “India and many African states may not have done so, but Mauritius, though I think there also has been some arm-twisting, could take no other stand but to condemn the invasion of Ukraine,” Boolell concludes. Now it remains to be seen what happens at the summit in July.

Source link : https://lexpress.mu/s/article/420646/war-ukraine-why-mauritius-taking-hard-line-against-russia

Author :

Publish date : 2023-10-28 16:36:41

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.