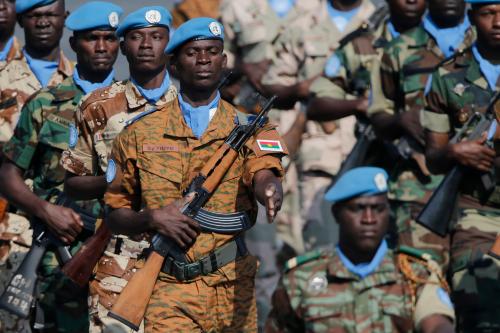

Nearly two years since Malian armed groups were brought to the negotiating table in Algiers to sign a contentious peace agreement with the government in Bamako, there appears to be little peace to be found. The 2012 Tuareg rebellion—the country’s fourth since independence—shook Mali and brought down the government of President Amadou Toumani Touré. It also led to the takeover of nearly two-thirds of the country’s landmass by non-state armed groups and an eventual jihadist occupation, both in Mali’s arid north. A French military intervention in January 2013 stopped the rapid expansion of these jihadist forces into southern parts of Mali and also allowed the gradual reconquest of the territory by Mali’s armed forces. However, the process remains incomplete, and both the government of Mali and its French partner have struggled to establish a viable local order. Even as the French Operation Serval transitioned to the much more geographically expansive Operation Barkhane and then the U.N. Multidimensional Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) over time deployed 12,500 peacekeepers into the country,1 peace and security have been elusive. In January 2017, a massive suicide car bomb ripped through a gathering of former combatants who registered with the government body responsible for coordinating joint patrols of armed nonstate groups and Malian forces, which was meant to be an essential confidence-building measure between the different armed groups and the government. The attack, claimed by a wing of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), killed at least 61 combatants and Malian soldiers, though reported tolls were much higher.2 At least 150 people have been killed in attacks in 2017 alone, many in attacks claimed by a fusion of jihadist groups active in Mali whose creation was announced in March 2017, the Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa al-Muslimeen, or the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (GSIM).3

The current difficulties in establishing effective and sustainable local order under the government’s control echo previous struggles in Mali to establish effective and inclusive governance. Various Malian governments have responded to rebellion and non-state violence through a mixture of repression, decentralization, reintegration of combatants, and cooptation of local elites who had their own interests and wars to fight, licit and illicit businesses to expand and defend, and political and economic scores to settle.

In response to the 2012 rebellion, the government of Mali has revived these same old policies while governance failures and corruption persist and abound. Not only has the government shown itself to be ineffective before, the situation in Mali has changed significantly since even the signing of the 2015 accords, raising further questions about the government’s ability to uphold its end of the bargain.

There is also a real danger that armed groups will once again appropriate governance in the north, whittling away at the influence of the state in an insidious manner. Such local governance by local armed groups may not always be bad for local populations in northern Mali. Some may even welcome such a development. But such a policy continues to undermine the state. Moreover, any semblance of peace between armed groups rests on a series of tenuous agreements kept in place for the moment by access to trafficking revenue and the prospect of funds from the government and international community.4

This report traces the evolution of local orders in Mali. It briefly discusses past governance practices and the outcomes of prior rebellions in the 1960s, 1990s, and 2000s. It then turns to the period following the 2012 peace accords and presents analysis on the current prospects for these agreements, as well as other stabilization and state-building measures. This report also analyzes the ways in which governance shortcomings continue to undermine security in the country. Indeed, existing government and international efforts to make short-term peace in Mali are at odds with long-term stabilization goals. Counterproductively, they reinforce social and ethnic tensions and strengthen non-state armed groups while hampering efforts to establish capable and legitimate state institutions in northern Mali. Regional and international actors should not allow the state to repeat past mistakes in the hope of a creating a different outcome.

Several specific policy implications follow from this analysis and basic argument:

Any and all local political solutions to Mali’s conflict must include the central state and be buttressed with support from the Malian government.

Long-term stability requires effective, sustained state-building efforts and security sector reform.

The government of Mali should stop using ethnic or tribal militias to maintain security in northern Mali, as this approach has consistently backfired and only further fueled communal violence and feelings of being ignored by the state. At the same time, international agreements like the Algiers Accords must be implemented fully, including efforts at decentralization accompanied by government support and real autonomy, to allow genuine power-sharing in the north, rather than parceling out pieces of territory to armed groups.

Finally, while local agreements can form the basis of more durable cessations of violence, these agreements must take place in consultation with diverse local populations. The Malian government and its international partners must be sensitive to the desires and concerns of these communities, rather than accommodating just the requests (or demands) of armed groups due to a mistaken assumption that these groups fully represent the interests of communities in the areas in which they operate.

Source link : https://www.brookings.edu/articles/reconstructing-local-orders-in-mali-historical-perspectives-and-future-challenges/

Author :

Publish date : 2023-06-27 04:16:48

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.