This study is among the first examples of a large scale citizen science project systematically implemented across multiple communities in several SSA countries. It leveraged co-design and community engagement approaches to generate rich, country-specific data to inform decision making targeting the prevention of CVD [24, 31]. The main findings were: i) the perceived causes of CVD in all the countries were similar, but participants unexpectedly emphasised other indirect factors (such as litter, poverty, substance abuse, crime, violence, stress, loss of job/relative) which were not consistent with most conventional causes of CVD (i.e., physical activity, diet, cholesterol, lifestyle, and hereditary factors). Notably, crime and substance abuse were major issues in South Africa relative to elsewhere; food-related factors was dominant in Malawi, food-related and emotional factors were dominant in Ethiopian communities.

ii.

trained citizen scientists successfully facilitated co-learning and co-production activities besides data collection, analyses, presentation and facilitation of advocacy workshops;

iii.

the positive factors perceived to mitigate effect of CVD were mainly nutrition or food-related, physical activity, and green space (i.e., clean and peaceful communities). These positive factors were directly connected with the reported perceived causes in each community; and; iv) through advocacy workshops and IKT activities, stakeholders in each country (especially those in health sector) had supported prioritization and begin to implement some locally-relevant CVD risk prevention solutions, including CVD risk screening and referral to care.

In our study, we had observed that learning together and engaging community members in different settings as citizen scientists enabled the researchers and communities in identifying the most needed and meaningful science-enabled activities of relevance to these sub-Saharan countries. The results of this study indicate that multi-country community-driven citizen science projects can facilitate effective multi-level engagement and participation of community stakeholders (including both community members and policymakers) in exploring CVD perceptions and supporting the co-creation, co-development, advocacy and implementation of contextually relevant health interventions in SSA [15, 38]. The summaries of the implications of the main findings are discussed below:

Perceived cardiovascular disease causes and mitigating factors by setting

The concerns around CVD and the perceived risk observed extended beyond the conventionally known risk factors (diet, physical activity, drug and substance use, etc.) in all the countries. These (additional) perceived factors included poor sanitation/hygiene, litter, crime, emotional stress, poverty, poor quality cooking stoves, and unrest/fighting. Consequently, using the findings, the citizen scientists and stakeholders (during advocacy workshops) had proffered solutions that were considered community-relevant to address these perceived extra-causes, particularly in the urban sites in South Africa, Malawi, and Ethiopia. Based on these findings, community-specific health promotion and education intervention were commonly indicated as preferred prevention strategies (see Table 3). A more detail findings on the CVD causes, mitigating factors, and their implications in each country and settings is documented in another paper under review for publication (Okop et. al.- forthcoming).

Citizen Scientists facilitated collaboration, co-learning and co-creation

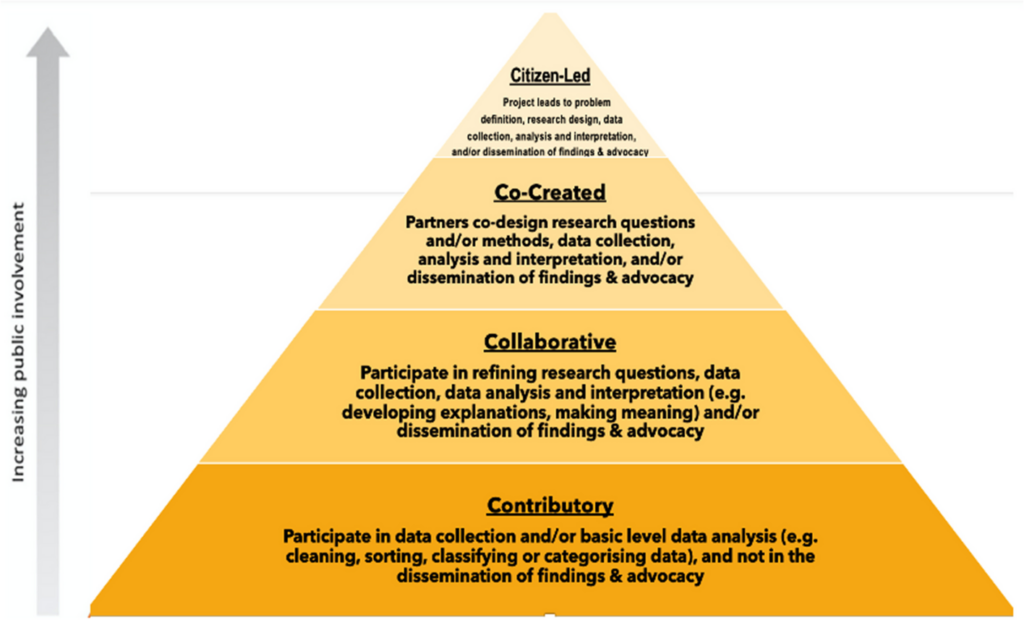

Through this study, communities (and citizen scientists) were empowered to collaboratively engage in science to: i) explore the perceptions and communication of CVD risk in their setting; and ii) support advocacy for CVD risk prevention using the evidence generated from the collaborative approach. It is believed that the collaborative approach facilitated co-leading of this multi-setting research project that helped foster an authentic partnership between the formal scientific community and groups of community members and stakeholders, as opposed to having the researchers try to “go it alone” without the indigenous context learning, planned researcher support, training, and co-production [14]. Participatory methodologies have been very useful in the co-creation, co-production and evaluation of public health interventions [39, 40]. The citizen-engagement, co-learning, co-design processes helped in eliciting knowledge and learning that were acceptable and trusted by the community to assist in the development of relevant and more meaningful CVD risk communication and prevention strategies. For instance, in all four project countries, an important barrier to prevention of heart-related diseases was found to be the poor perception, knowledge and awareness gap with regard to CVD and their risk factors. Notably, community members and stakeholders recommended interventions in each community to address the poor perception and awareness gaps in both the rural and urban communities.

Importantly, the trained citizen scientists gained transferable scientific skills, including hands-on training in conducting community-based surveys, use of mobile devices for systematic interviewing and data gathering, data extraction methods, simple analysis (compiling the findings in a usable, meaningful format), and presentation of findings as part of the stakeholder advocacy workshops. A majority of the citizen scientists shared their utmost excitement at being given an opportunity to learn to lead research and prevention advocacy activities as “community scientists”. They described their feelings of personal satisfaction and fulfilment as “local scientists” capable of engaging in community-driven indigenous science through anecdotal reporting from their project teams and during stakeholders’ workshops.

Collaborative prioritization and implementation of locally-relevant solutions

Through advocacy workshops and IKT activities, stakeholders in each country were able to support the prioritization and implementation of locally-relevant solutions for CVD risk prevention. This approach helped empower communities to take action to improve their health and wellbeing by first taking a lead in exploring CVD risk, collecting and analysing data, identifying, and prioritising community-based strategies, and, finally, mobilizing support and advocacy for sustainable solutions [15]. For example, in Ethiopia (rural and urban), following community advocacy workshops, the stakeholders in collaboration with the Ethiopian AHRI (Armeur Hansen Research Institute) project team supported the re-training of 12 health extension workers (HEWs) on blood pressure screening and CVD risk screening. The trained HEWs conducted a 4-week CVD risk screening intervention programme in 10 communities using a mobile app. The persons who were identified as high risk for CVD (124 out of 3000) were referred to designated clinics for care. Besides Ethiopia, CVD risk screening and referral to care interventions were successfully implemented in Rwanda and Malawi. In South Africa, community-engaged CVD risk prevention health promotion and screening programme were identified as an essential strategy for addressing CVD prevention in the townships.

It was a great achievement to see some of the suggested community-level prevention intervention strategies (i.e. nutrition, physical activity, and sanitation and hygiene) being planned and implemented in Ethiopia and Rwanda following the stakeholders’ advocacy workshops in these countries.

Previous studies and the methodological gaps

The use of citizen science and co-design approaches in developing interventions in different fields is growing, particularly in develop countries. In the context of adopting these approaches to CVD prevention interventions in multiple SSA, literature from SSA is, however, scarce. A recent study conducted in Birmingham, UK had showed that citizen scientists participated in over 12 technology-enabled assessments and supported the identification of urban features impacting age friendliness [39]. They also utilized that findings and engagement to co-produce recommendations to improved local urban areas towards active aging in urban settings. The above study is akin to our study. However, our study focused on multiple urban and rural settings in four countries, and not just on one particular city.

Although the community-based interventions are being implemented, there is a gap of non-collaborative and or non-participatory intervention approaches. For instance, a recent systematic review had reported that community-based interventions had successfully improved knowledge and create awareness on CVD and risk factors and influence physical activity and dietary practices in the developed country communities [4]. However, although most of these interventions were delivered by healthcare workers, CHWs, and volunteers, the studies did not specifically incorporate the citizen-engaged (citizen science) participatory approach in their delivery. Thus, resulting in the lack of co-designed evidence-based interventions that are tailored to the individual settings/communities. Also, these interventions were mainly conducted outside of Africa. Another recent review reported on patient active involvement and the use of m-health in supporting physical activity and co-production of health policies aiming at CVD prevention. Findings from that review indicated that patients (and beneficiaries) participations in interventions co-design process, though recognized as fundamental for CVD prevention, were lacking [20]. Our study had employed citizen science and co-design approaches to facilitate multi-level stakeholders’ engagement, participatory learning, adaptation of tools, and support co-creation of knowledge, and advocacy for social action. This is akin to the study conducted by Wallersteine et. al, and those indicated by Boeder and colleagues [21, 22], except that their studies were not undertaken in multiple settings. Importantly, our study had also involved multi-level stakeholders including decision-makers and community members from the onset of the research processes, and in prioritizing evidence-based interventions and implementation actions. Our study, therefore, closes the methodological gaps in designing and implementing community-based participatory citizen science projects in multiple low-income settings.

Challenges and lessons learnt

This research, the first of its kind in exploring CVD risk perception and co-developing prevention strategies and advocacy in SSA settings, adds value to citizen science research and methodology globally. There were, however, challenges encountered during the study. While the initial meetings of the research teams and consultations with stakeholders in each country took place before the pandemic, the COVID-19 restrictions heightened the challenge of meetings timely in all the countries during the co-designing and implementation of projects. It was expected that much of the collaborative citizen science research activities needed to be facilitated by the beneficiaries (citizen scientists and stakeholders) but, due to COVID-19, we experienced delays in scheduling timely consultation meetings with the stakeholders. As a result, the project team had to exercise a great deal of patience in re-scheduling meetings and being able to work with the citizen scientists and stakeholders at the times they were available. In addition, there were delays in some settings (particularly in the rural communities) in getting the citizen scientists (after data collection) to support organizing the narratives and photos, data analysis and results interpretation. We also observed that 2–3 days of training of the citizen scientists was not sufficient to build their capacity to support the data collection, organization and analysis, and presentation as expected. In some countries, we had to organise additional training sessions for the citizen scientists to further enhance their skills. Future studies of this type will need to pay particular attention to such constraints and continue to work on creative ways for mitigating them. The key lessons learnt include: i) ensuring active participation of citizens in exploring CVD perceptions, co-designing and implementing research can support participatory engagement for inclusive learning, co-designing, and co-creation intervention actions to address CVD prevention. ii) the process of producing reliable knowledge can be developed and enacted by citizens themselves with support from researchers; iii) importantly, working with teams across multiple countries and settings to support efficient research implementation and intervention sustainability requires dedicated resources, and adequate time allocation for team building and co-learning from the planning to evaluation stage.

Study strengths and limitations

This study used robust systematic and community-engaged processes to support participation of multi-level stakeholders in participatory research towards addressing local health problem with community-specific solutions. The collaborative methods supported active and productive citizen-led participatory research engagements. The study has some limitations. It was conducted only in selected communities in four countries in SSA, and therefore, the findings may apply in each individual project country, but may, however, not be generalizable in the SSA region. While the citizen science project was conducted in Rwanda the photo-voice data on CVD risk perception were not available for analysis. However, findings of this study can be utilised to support CVD prevention programmes in similar settings in SSA. It is important to note that the citizen scientists undertook the data collection, analysis, and outlined key findings that they prioritized for presentation to stakeholders during advocacy workshops. We, therefore, believe that the citizen scientists’ views on key issues, prioritized health problems and prevention strategies might be partly affected by their personal exposure, cultural perceptions, experience and learning.

Implication for policy and practice

This citizen science study included citizen engagement, participation and involvement that conventional science often lacks. It emphasizes working with communities, volunteers, and multi-level stakeholders to support participatory learning and engagement to gain knowledge and context-based research perspectives that can impact society. Findings from this study have indicated the possibility of supporting the co-designing of CVD prevention strategies and actions in the context of multiple low-income settings in Africa. The collaborative identification of the community-level perceptions, barriers and facilitators of CVD prevention, and the subsequent prioritization and implementation of locally-relevant actionable solutions in the different settings are important lessons. Notably, the engagement with stakeholders resulted in the implementation of a pilot citizen science-informed CVD risk screening and referral to care project in three countries. This collaborative citizen science approach can be extended to other areas of public health to support the co-development of evidence-based solutions tailored to community needs.

Source link : https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-023-17393-x

Author :

Publish date : 2023-12-12 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.