In the wake of civil war, Liberia vows to better manage its forests

After Liberia’s civil war came to an end in 2003, aid agencies and U.N. peacekeepers flooded into the country to fill the void left by its toppled government. It was by then a devastated nation: 250,000 people had died in the fighting and an additional 750,000 had fled their homes. Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, a former World Bank official, was elected president in 2005 on a reform agenda.

Near the top of that agenda were Liberia’s outdated forest laws, and for good reason. Illicit logging had fueled the conflict, with warlord-turned-president Charles Taylor’s government swapping timber for weapons in a scheme that had extended the conflict and helped spread it to neighboring countries.

“The donors, Liberian civil society, and the communities themselves — literally everybody wanted to see some really drastic changes in the way the forest sector was being managed, especially with respect to logging operations,” Silas Siakor, a Liberian activist and Goldman Environmental Prize winner, said in an interview with Mongabay.

For Siakor and other reformers, the choice was clear: Liberia had to change how it had been doing business in its rainforests and start giving people who lived in them a seat at the table. With the support and encouragement of the U.S. and other postwar donors, in 2005 Liberia enacted the National Forestry Reform Law, which reworked the way logging contracts were managed and mandated the development of a new community forestry system.

That system was born via the 2009 Community Rights Law, which established the legal framework for community forestry in Liberia. Communities that wanted decision-making rights over their traditional forests could now go through a series of steps that would culminate in the election of a board, development of a management plan, and the FDA’s formal recognition of their authority.

The new law had teeth. Loggers were barred from harvesting timber inside a community forest without the written consent of the management committee, after consultations with the wider group that elected them, and would have to pay a sizeable portion of their revenue into a community development fund.

For Siakor, it was the culmination of years of advocacy and hard work.

“It was a big deal. For the first time, we were coming from a situation of total exclusion and marginalization to a situation in which the community’s right to manage its forest was being recognized and formalized,” Siakor said.

But setting up the new structures was costly, difficult and time-consuming. Literacy rates in the towns and villages that would be applying for the permits were low, and training board members to carry out their new responsibilities wasn’t going to happen overnight. The FDA was tasked with supervising the application process, but like most Liberian government agencies after the war it was underfunded and struggling with a dearth of qualified managers.

Parts of the donor community saw an opportunity. Liberia was a crucial biodiversity hotspot, containing nearly half of West Africa’s remaining upper Guinean rainforest. But pressure on the government to raise revenue was high, and a wave of investment deals were rapidly being inked with mining and palm oil companies, some of which crept up to the edge of high conservation value rainforests — or even overlapped with them.

For some of Liberia’s international partners, community forests were a solution that could help bridge the gap. The law permitted logging, but if some of the communities were given the right support, they might be pushed toward rainforest conservation instead.

The U.S. and Norway took the lead. USAID began with an $8 million project that provided support to three pilot community forests in Nimba, including Blei. In 2012, it followed with a five-year, $20.4 million contract granted to the U.S.-based consulting firm Tetra Tech to implement a project that expanded USAID’s support to include nine new community forests. In all, USAID would eventually spend more than $50 million on community forestry in Liberia by 2020.

As part of its own landmark $150 million deal with the Liberian government designed to prevent deforestation, Norway joined the World Bank in spending $10.5 million on a community forestry support program that was connected to REDD+.

Right as USAID’s expanded project kicked off in 2012, a scandal erupted in another corner of Liberia’s forestry sector. A loophole in the forest reform laws had been exploited by corrupt public officials, logging companies, and in some cases members of forest communities themselves.

In just two years, dubious land titles, some forged, had been used to hand out almost half of the country’s forests to loggers.

“You had these private sector actors — whether it was at the national or local level — taking advantage of weak governance to exploit the population,” Siakor said. “It was a total breakdown of the rule of law.”

The embarrassing scandal wasn’t directly connected to the nascent community forest system, but it was an ill omen for what lay ahead. No matter how strong the new laws looked on the books, without the political willpower to back them up they were just words on paper.

The Solway Investment Group’s “Fenix” ferro-nickel production facility in eastern Guatemala has been plagued by allegations of pollution and disputes with local Indigenous groups. Sandra Cuffe for Mongabay.

From Russia to Switzerland to Nimba

At first, Thompson had trouble finding out who the company that had entered Blei was or where it had come from. The details were vague, but eventually a name emerged: Solway Mining Incorporated.

In an emailed statement to Mongabay, a spokesperson for Solway Mining Incorporated confirmed that the company is a subsidiary of Solway Investment Group, an international mining and metals firm with operations across the world. On Solway’s website, it says it specializes in “projects that are not as attractive to major market players because of complex local social and economic conditions.”

Solway is headquartered in Switzerland, but has its origins in Russia. According to Forbes, Solway’s founder, Daniel Bronstein, is a former Soviet official who earned much of his fortune through aluminum smelting deals during Russia’s privatization whirlwind of the 1990s and early 2000s. Bronstein’s business partners have included high-profile Russian oligarchs such as the billionaire Viktor Vekselberg, who in 2018 was placed on a sanctions list by U.S. authorities.

Among Solway’s investments is a troubled nickel mine in Guatemala that has a years-long history of conflict with nearby Maya Q’eqchi communities who have accused it of polluting waterways and failing to respect coronavirus restrictions. In 2017, Guatemalan police opened fire on protesters who were demonstrating against the mine, in an incident that forced a local journalist into hiding. Solway has also been accused of using “transfer pricing” to underpay revenue obligations to the Guatemalan government.

Boimah Morgan, Solway Mining Incorporated’s Liberian CEO, emphasizes the parent company’s base in Switzerland, telling the Liberian press that insinuations of Russian influence made by local journalists are a “manipulative suggestion aimed at damaging the company’s reputation.”

In 2019, Solway was granted a permit to explore for iron ore on 152 hectares (376 acres) of the Blei forest and an additional 70 hectares (173 acres) of another nearby community forest.

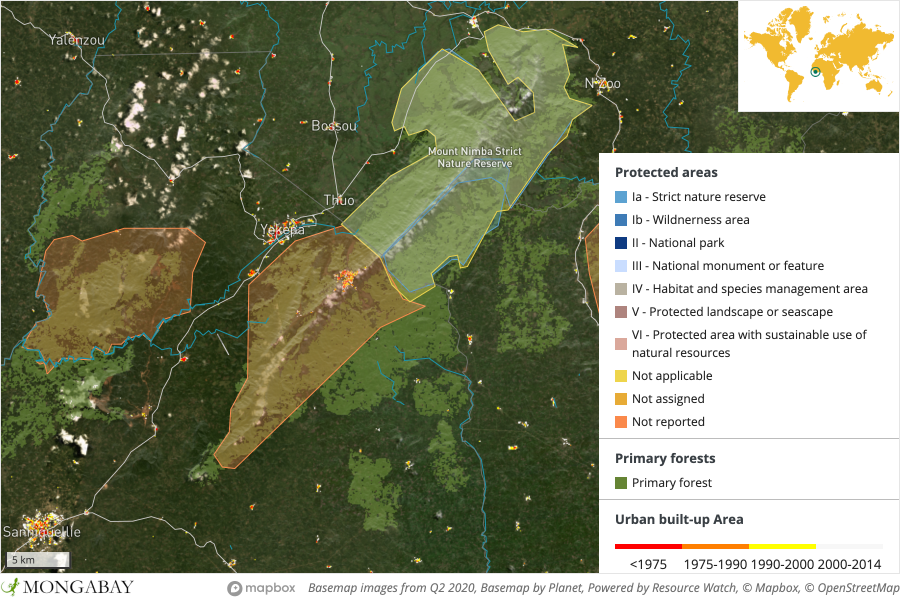

A satellite map of the border between northern Liberia and Guinea. The Blei Forest lies along the southernmost tip of the East Nimba Nature Reserve – the orange area that joins the Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve.

A satellite map of the border between northern Liberia and Guinea. The Blei Forest lies along the southernmost tip of the East Nimba Nature Reserve – the orange area that joins the Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve.

After the court ordered a halt to Solway’s operations, Thompson traveled to Monrovia to directly appeal for help from the FDA, hoping it would intervene in support of the law. But he says the official in charge of supervising community forestry told him her hands were tied.

“My brother, this is Liberia business,” he recalls her saying. “If we put our mouth inside this issue we will lose our jobs.”

He would, she told him, have to fight the battle on his own.

In Blei, Solway was hard at work trying to undercut Thompson’s opposition to its operations, handing out gifts and making promises of employment to come.

“We brought like 40 chiefs together to discuss this with them, and we came to the conclusion that the people needed some form of compensation,” Morgan said in an interview. “So I worked out an agreement with them.”

The communities around Blei were poor, and forest conservation had brought few tangible benefits. For many, the allure of an international mining firm with deep pockets overshadowed any attachment they may have once had to the conservation plan.

Thompson began to receive threats. The dispute had embroiled Blei, and on the radio he overheard a man suggest he might disappear if he didn’t drop his opposition to the project. Local politicians were accusing him of lying to the community and blocking economic development. In the end, it was too much.

In late April, as the coronavirus pandemic raged, Thompson sat down with Solway representatives, the other board members, and a group of local government officials. Exhausted and against his better judgment, he signed a memorandum of understanding that formally invited Solway into Blei’s forest and obligated the community to abandon its prior conservation management plan.

The MOU is light on details. It makes no promises that Solway will provide a set number of jobs to residents of Blei, nor that its operations won’t irreparably damage the forest. Liberia’s mining law requires investors to pay 2% of their exploration budget on health and education for nearby communities, and a provision of the MOU says those funds will be deposited into an account controlled by the community forest board.

That sum could amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Given Liberia’s recent history with community revenue-sharing, however, it is far from certain those funds will be paid on time — or at all.

Ten years, a headline-grabbing legal reform, and millions of donor dollars later, it was still an all-too-familiar story. After a decade of intensive support and training to the community board responsible for acting as a check on exploitative natural resource deals, it had been thoroughly pushed to the side the first time the system was put to a real test.

Thompson says he regrets signing the MOU, but in the absence of any meaningful support he felt he had no choice.

“There’s nothing in there,” he said. “No infrastructure development, no employment opportunities, nothing.”

Source link : https://news.mongabay.com/2020/12/liberia-gave-villagers-control-over-their-forests-then-a-mining-company-showed-up/

Author :

Publish date : 2020-12-22 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.