In a critique of West Africa’s Liberia in 1958, the Black American sociologist and commentator W.E.B. Du Bois commented that “a body of local private capitalists, even if they are Black, can never free Africa; they will simply sell it into new slavery to old masters overseas.”

At the time, Liberia had the second highest economic growth rate in the world. Liberia’s open-door policy had seen private foreign capital investment boom in the postwar period, as companies were granted land concessions and given tax breaks, incentivized by low wages and low regulation. Despite these impressive growth rates though, “a handful of American-owned companies and about 1,000 Americans working in Liberia [made] more money in Liberia than all Liberians put together.”

Empire of Rubber: Firestone’s Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia, Gregg Mitman, The New Press, 336 pp., .99, November 2021

Empire of Rubber: Firestone’s Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia, Gregg Mitman, The New Press, 336 pp., $27.99, November 2021

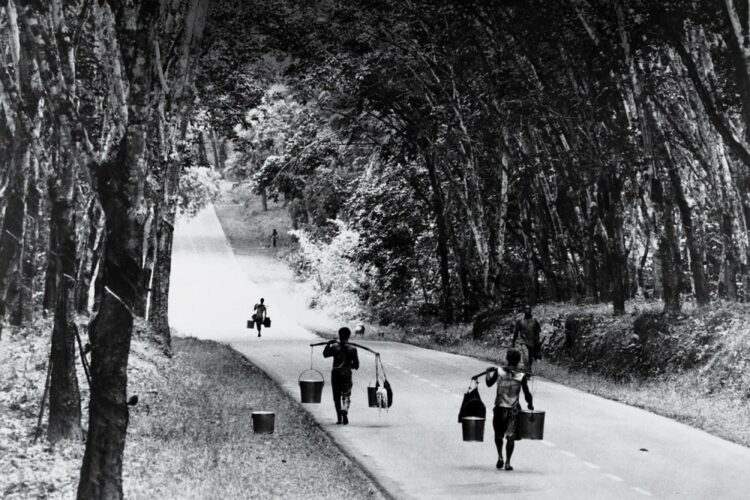

Gregg Mitman’s Empire of Rubber: Firestone’s Scramble for Land and Power in Liberia is a fascinating and enlightening page turner that uncovers Liberia’s often overlooked importance in U.S. history. Without Liberia, founded by U.S. settlers in the 19th century, the Allies would not have been able to produce enough rubber to win World War II. In 1944, Firestone Rubber was the largest employer in all of Liberia. And without the investment of Firestone, Liberia’s independence and its status as the only Black sovereign state in Africa would have been threatened by Britain, France, and Germany. How did a Black republic and Firestone, a manufacturing firm from Akron, Ohio, find their fates so intertwined?

Sovereignty was at the heart of a dilemma faced by both the United States and Liberia. By the end of the 19th century, Britain, France, and the Netherlands had all colonized places in tropical climates suitable for establishing rubber plantations, leaving U.S. manufacturers dependent on foreign imports. When, at the end of World War I, the British and Dutch imposed new restrictions on exports and new price minimums, companies like Firestone reached out to the U.S. government to seek support for plans to establish rubber plantations in places friendly—or beholden to—the United States: The Philippines and various options in Latin America were floated, but ultimately, Liberia was chosen.

This choice came about, Mitman shows, through a combination of history, lobbying, and luck. Black American emigrants had settled in the region from as early as 1821, sent by the controversial American Colonization Society. Despite strong opposition to the American Colonization Society’s project from a “majority” of Black people, 10,000 Black Americans settled in dispersed towns along the Liberian coast by the end of the 19th century. Liberia inaugurated its first government as an independent republic in 1848, though it retained a special relationship with the United States.

Meanwhile, as Mitman explains with devastating clarity, in a world of expanding empires, Liberia sought out financial capital that would enable it to retain independence and self-governance—but which wound up tying it into Britain’s sphere of influence and debt. “How could the country remain sovereign in a world ruled by the power of white capital and Western imperialism?” Mitman asks. Was strategically ceding economic sovereignty to maintain political control the right choice?

As a Black republic, Liberia had not only strategic economic importance to Americans but also symbolic political importance. An independent and flourishing Black republic could demonstrate to the world that Black people were not inferior. This argument was not merely theoretically important. Deep-seated racism, backed up by so-called race science, dominated geopolitics at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. During that time, the rest of Africa was colonized, and racial codes like Jim Crow laws as well as laws restricting immigration flourished in white majority countries. The prevailing racial arguments rested on notions of white superiority that pointed to specific markers of “civilization” and development. Because places that had a Black majority were deemed underdeveloped, backward, and “uncivilized,” white people were deemed to have a moral duty to improve them in ways Black leaders were deemed incapable of doing. Poverty and skin color were seen to be one and the same.

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt is welcomed to the Firestone rubber plantation during a trip to Liberia in January 1943.

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt is welcomed to the Firestone rubber plantation during a trip to Liberia in January 1943.U.S. Navy/library of congress

Liberia stood out as a hope to people across the political spectrum—from the radical activist Marcus Garvey to the more moderate Du Bois and the conservative author Booker T. Washington—because it was self-governing and demonstrated Black people could be equals in the world of sovereign states.

But true sovereignty had to come with proof of development, and development was only possible through investment. This search for financial capital was the real goal for Liberia—one that would have been familiar to many states at the time. From the late 19th century, both Britain and France hoped to take territory formally claimed by Liberia (and, as Mitman regularly reminds readers, taken by Liberian settlers from people belonging to the Vai, Dei, Gola, Kru, Kpelle, Bassa, Loma, Kissi, Gbandi, Sapo, Mano, Mende, Mandingo, Gio, and Kuwaa). The accusations Britain and France made to justify this included that Liberia was underdeveloped and didn’t have a big enough government to effectively occupy and improve the whole territory it claimed.

Enter Garvey, the Back-to-Africa proponent and radical activist who offered Liberia capital raised through bonds sold in his Black Star Line to clear British debts. This was not as straightforward a proposal as it might seem though. Du Bois and other Liberian advocates raised questions about its feasibility and also about Garvey’s intentions. Garvey had targeted the Liberian political and economic elite as being corrupt and insular while ignoring the rest of the Liberian population’s poverty. Du Bois worried that questioning Liberia’s governance would give white governments an excuse to take control of the country.

Firestone offered another option for both the United States and Liberia. An independent source of rubber would provide security to U.S. manufacturing supply chains. Private finance would give Liberia more bargaining power and prevent its takeover by another government. Both Firestone and Liberia hoped to outwit the financiers who were profiting from the status quo. After several years of negotiations, investigations, and government lobbying, an agreement was reached in 1926. Firestone would pay an annual rent of $1 an acre (and 6 cents per acre for additional land leases up to a million acres) to the Liberian government as well as pay 2.5 percent on all rubber sales and agreed not to import unskilled labor. But Harvey himself inserted a last-minute addition of a $5 million loan—an attempt to tie the U.S. government’s interests to his company’s. Mitman recounts that “Firestone told members of Congress that a private loan, supported by American diplomatic pressure, and guns if necessary, was the best means to ensure adequate protection” of his investment. Du Bois had hoped Firestone would “allow in Liberia decent and increasing wages” and the “Liberian government satisfactory revenue.” He was disappointed when the government was ultimately strong-armed into an agreement where it retained judicial control but little else.

The conflict between Garvey and Du Bois is representative of one of the most appealing aspects of Mitman’s writing. The range of characters he introduces are all drawn as full and fascinating individuals with complex politics. The book makes a compelling case that representation alone is rarely enough—either at the national or individual level—in that it has not necessarily advanced the conditions of the economically oppressed. Many Black politicians, diplomats, and educators who were invested in Liberia’s promise were educated at Harvard University, Columbia University, Howard University, the London School of Economics and Political Science, and other elite institutions. They were newspaper reporters, entrepreneurs, sociologists, historians, agricultural experts, anthropologists, diplomats, politicians, and financiers. Liberia’s very existence furnished the United States with the opportunity to send its best and brightest Black talent into “solving” this intractable international relations and development puzzle.

For instance, there was William Francis, the U.S. consul to Liberia at the end of the 1920s, who began the U.S. State Department’s secret investigation into the country’s use of forced labor. And Lester Walton, who had “little patience for critiques of capitalism calling for liberation of Black labor from white oppression through working-class revolution.” An active member of New York’s Democratic Party and the person responsible for encouraging U.S. newspapers to “print the word Negro with a capital N,” Walton was involved with Firestone’s bid to “save Liberia” from exploitation by Liberia’s ruling elite. The accusations divided opinions. Should the United States intervene on humanitarian grounds in support of exploited workers, undermining Liberia’s sovereignty? Or was it better, as Du Bois found himself reluctantly arguing, to ignore the exploitation and support the country’s broader claim to sovereignty?

The Liberian administration was not without guilt. Labor was one of the few forms of “capital” it could access freely without creating international dependency. Also, like other governments of the time—including the United States—the Liberian government used forced and conscripted labor for construction projects like building roads and clearing land. The ruling elite passed laws that favored their own class and looked the other way at their blatant corruption. The country’s development undoubtedly reflected stark conditions of inequality. But as Liberia’s advocates regularly pointed out, these statements were also true of Africa’s European empires—and were equally true of the United States itself.

The perpetual question of either race or class interest’s superiority came to a head during the Cold War. The group of Liberian capitalists who established their own rubber plantations alongside Firestone—and who were therefore economically aligned with Firestone’s goals in the country—found themselves facing down labor unrest from economically exploited workers. Liberian President William Tubman, who had the largest rubber plantation outside of Firestone control, used martial law to put down a strike at Firestone in 1950. But at the same time, the Firestone premises were segregated, with even Black diplomats and Liberian officials denied access to some white-only spaces. During the 1960s and into the 1970s, that alliance shifted as Pan-African movements, the development of international arguments for the Black Power movement, and anti-colonial sentiment combined with labor activism to push Tubman’s successor, William Tolbert Jr., to finally renegotiate the terms of concessionary arrangements like Firestone’s. But it was too little, too late.

Mitman’s narrative illustrates a pattern in the battle between government and private capital. First, Britain provided the capital to allow Liberia to be truly independent. Firestone would then be the savior because it would eliminate Liberia’s reliance on foreign government loans. The Liberia Company, a joint-venture mining operation that ran from the end of World War II until 1962, was proposed to rescue the country from dependence on Firestone. The company was part of a broader set of interventions supported by U.S. President Harry Truman’s post-World War II Point Four Program, which sought to rescue Liberia through a “concept of partnership and social responsibility.” And then Tubman’s open-door policy would free Liberia from any potential neocolonial dependency on the United States during the Cold War.

The book makes clear the stark choices faced by all kinds of places where capital is in short supply. There are obvious modern parallels to campaigns by cities and states to recruit Amazon warehouses through tax incentives or different countries to compete over tax or regulatory regimes in a bid to attract multinational corporations. Throughout the brilliantly told narrative, Mitman highlights some of the possible exit strategies Liberia has had along the way. Garvey’s Black Star Line was one. An agricultural expert named Frank Pinder sent by the Truman administration after World War II presented another. He proposed a shift away from monoculture and concessions and toward Liberian-led commercial agriculture following traditional farming practices.

The passage of the 2018 Land Rights Act, championed by rural women, is the latest source of hope. And in it, Mitman sees the promise of a Liberian economic and political future focused on sustainable growth and development. The enduring tension between international capital and sovereignty, he proposes, can be overcome by a focus on community sovereignty and local investment instead.

Update, November 2021: The final amount for land in the Firestone agreement has been added.

Correction, Feb. 14, 2022: A previous version of this article misdated W.E.B. Du Bois’s quoted comments on Liberia. It has been fixed.

This article appears in the Spring 2022 print issue. Subscribe now to support our journalism and get unlimited access to FP.

Source link : https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/11/06/liberia-firestone-rubber-capital-us-war-review-gregg-mitman/

Author :

Publish date : 2021-11-06 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.