Broadly, the political economy literature grounds Ghana’s road transport problems at the crosscutting edges of both local/internal and global/external factors. An important local factor emphasized in the literature as central to road transport problems and, thus, critical to establishing the grounds or structural context for the deleterious consequences of road trauma in the country is the failure of successive governments to invest meaningfully in rail and public bus transport and other infrastructure to support non-motorized transportation systems (such as bicycle lanes). This has meant that Ghanaians rely heavily on imported cars–either as owners or as passengers (Obeng-Odoom, 2013). Nonetheless, the failure of the Ghanaian state to play a leading role in the provision of transport needs and services generally and the high importation of cars into the country are also linked to economic liberalization—an external factor. In the 1980s, Ghana’s economy tumbled forcing the then Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) military government to run to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank for support. Attached to the support offered by the Bretton Woods institutions was the condition that the government liberalize the economy (Boateng, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d; Obeng-Odoom, 2013).

Further to ‘advising’ the PNDC government to divest itself of its holdings in transport companies, liberalization reforms also opened the floodgate for increased importation of cars into the country—a development that has since remained a marked feature of Ghana’s transport sector (Burchardt, 2015; Obeng-Odoom, 2010, 2013). The problem, however, is that only a few number (8%) of imported cars in Ghana are brand new. The remaining 92% could be second-, third-, fourth-, or even fifth-hand cars (Burchardt, 2015; Obeng-Odoom, 2013). Some of the vehicles are so old that they have been nicknamed “Eurocarcas”. A study by the National Road Safety Commission (as it was then called) found that a significant proportion of the commercial vehicles in Ghana are old. The age profile is mostly above 5 years. Only 13% are below 5 years, about 34% are up to 10 years with those up to 15 years and above constituting over 50% (Obeng-Odoom, 2013). Research has shown that fatalities in older vehicles are four times higher than in new vehicles (see RACV, 2017). Indeed, a recent analysis suggests that while old vehicles make up just 20% of road vehicles globally, they constitute one third of all fatal car crashes (RACV, 2017). With the heavy reliance on old cars for commercial and other purposes, it is not surprising that Ghana experiences high rate of road fatalities. Further to incentivizing the importation of old cars into the country, economic liberalization also propagated a certain land-use pattern, which also contributes to road safety problems.

The reforms attracted enormous private capital often multinational but also local, investments into the country. Nonetheless, the tendency for private investors to strive to enjoy the perks of economies of scale meant that almost all the investments were directed to the old generalized growth areas or industrial enclaves—i.e., the big cities particularly Accra, Tema and Kumasi (Obeng-Odoom, 2010, 2013). The over-concentration of investments/business, and to that end jobs, services, trade and headquarters’ of public and private institutions in the cities, has meant that almost all the traffic in Ghana move to the same place, with the attendant repercussion for gridlocks popularly called “go slow”.The discourses on the adverse effects of traffic congestion in Ghana often focus on issues like productivity, air pollution and delays (Burchardt, 2015; Obeng-Odoom, 2010, 2013). Nevertheless, by holding drivers up on the road for extended periods, traffic congestions could also generate safety-adverse driving problems such as long hour and fatigue driving. Drivers, particularly commercial drivers, held up in traffic for long periods are likely to undertake aggressive and other safety-adverse driving practices to make up for lost time or potential revenue. Indeed, some empirical evidence has emerged that traffic congestions in the cities incentivize over-speeding—one of the main causes of RTCs in Ghana. For instance, some drivers submitted in Dotse et al. (2019) that they try to make up for the time they get hold up in traffic in the cities by increasing their speed on the highways—the so-called “good”roads in Ghana. One of the drivers expressed himself on the nexus between traffic congestion and over-speeding as follows:

….Driving from Accra to Kumasi should take about 4 h but because of the traffic you can be on the road for 6 h. … you can be in traffic alone for three hours and when you finally move through you want to speed to cover the time you spent in the traffic especially when the road is “good” (Emphasis added).

This may well partly explain the rather puzzling persistence of many RTCs on the “best” of Ghana’s roads (the highways) (NRSC, 2016; Afukaar et al., 2003). Further to the importation of old cars and land-use patterns-induced gridlocks–thanks to neoliberal reforms–there are other political-economic dynamics and contested power relations that are critical to understanding road safety problems in Ghana. One of them is high levels of unemployment. The mainstream discourses (see e.g., Baah-Boateng, 2013, 2015) on the causes of unemployment in Ghana largely focus on individual factors such as education, gender, age and marital statuses as well as people’s reservation wages and locations (whether they reside in a rural or an urban setting). Nonetheless, multiple systematic studies (see e.g., Arthur, 1991; Kendie, 1998; Owusu et al., 2008; Otiso and Owusu, 2008; UN-HABITAT, 2009 in Obeng-Odoom, 2013) have confirmed that the rising unemployment in Ghana and the attendant repercussions for the burgeoning informal sector are structurally embedded in bigger historical-political-economic factors and developments such as the massive reductions in public-sector employment; divestiture of public enterprises; the wage cuts and freezes and massive retrenchment exercises that came with structural adjustment reforms and have since remained key approaches of organizing socio-political-economic life by the Ghanaian state.

Regardless of the causes, studies (see, Oteng-Ababio and Agyemang, 2012, 2015) suggest that, together with the lack of viable organized public transport, the declines in opportunities for wage employment and unemployment generally in Ghana have led to a rapid growth in dangerous non-conventional transportation modes, such as the commercialization of motorcycles popularly called Okada. According to Ghana’s Road Safety Authority (NRSA), Okada alone accounted for 25% of the 1538 road fatalities recorded in the country in 2013 (Ghanaweb, 2013). Today, the chance of dying from an Okada crash in Ghana, according to the NRSA, stands at a troubling ten times higher than a car crash (Dapatem, 2020). Clearly, the proliferation of Okada in Ghana has been troubling. However, that is not the only way unemployment is influencing safety outcomes in the transport sector. The high level of unemployment in the country has also meant that, as with that of other African countries (Rizzo, 2011, 2017), Ghana’s commercial car transport sector attracts a large number of lumpenproletariat seeking jobs as drivers. The situation ordinarily puts car owners in a stronger position to impose unrealistic end-of-day-sales on drivers (Obeng-Odoom, 2010, 2013; Dotse et al., 2019). As with their fellows elsewhere in Africa (Agbiboa, 2015, 2016), the precarious conditions of commercial passenger drivers in Ghana are further worsened by the ever-present bribe-demanding corrupt police officers who have created a predatory economy across the passenger transport sector by extorting monies from drivers (Boateng, 2020a). The drivers could only make enough revenue to cover operational costs and the police bribes, pay their owners, themselves, and their assistants only by increasing the number of trips or passengers per trip. They, invariably, therefore, are forced or incentivized to drive for long hours, resort to dangerous overtaking, overload their rickety vehicles and drive at dangerously high speeds with repercussions for RTCs. One driver, for instance, submitted in Dotse et al. (2019).

Many of us drivers are rushing and the problem is because of the sales you have to make…when there are more passengers like funerals on Saturday, I rush so much so I can get more money to make my sales. Even if the car is for you, after spending money at the shop you are left with something small for yourself so you have to rush whenever there are passengers and you have to work all day. You sometimes become tired but you don’t have to stop.

Some commercial passenger transport drivers engaged by Klopp and Mitullah (2016); Klopp et al. (2019); Rizzo (2011, 2017); Behrens et al. (2016); McCormick et al. (2016a, 2016b), and Agbiboa (2015, 2016) reported similar experiences in Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, and Nigeria. Efforts by the Ghanaian authorities to improve the passenger transport sector have largely been non-committal. For instance, in April 2010, the government announced its intentions to revive the participation of the state in the commercial passenger transport sector by implementing a public-sector bus rapid transit system. However, the government balked at the plan when it was pressured by the coalition of private transport owners’ unions who felt the intervention will take away their business (Obeng-Odoom, 2010, 2013). The plan was aborted partly because private transport owners’ unions such as the Ghana Private Road Transport Union (GPRTU), the Progressive Transport Owners Association (PROTOA), the Ghana Co-operative Transport Association (GCTA) and the Ghana National Transport Owners Association (GNTOA) wield enormous political influence. Not only do they have substantial membership base that could decide elections, they also are a significant source of revenue for the government. From 1987 to 2003, the GPRTU, for instance, was collecting income tax from its members for the government. It is an arrangement that was entered into because of the lack of information about the earnings of drivers and transport owners (Obeng-Odoom, 2013). As such, successive governments found it useful to maintain the arrangement, as it provided one solution to the problem of informality, until the NPP government replaced it in 2003 with the current Vehicle Income Tax system, which requires drivers to instead pay tax on a quarterly basis (Burchardt, 2015).

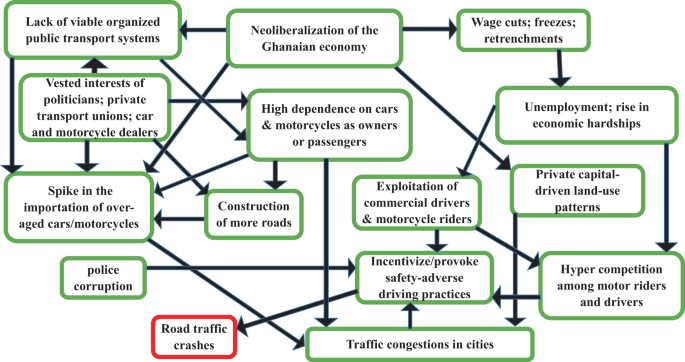

Further, the members of the coalition of private transport owners’ unions in the country have the potential to disrupt political rallies if, through a strike, they refuse to provide mass transportation of party supporters to rally grounds. Indeed, Ghanaian drivers have a well-documented history of disrupting the country’s socio-political-economic life with strikes (see Hart, 2013). Politicians’ fear of incurring the wrath of the coalition of private transport owners’ unions has meant that successive governments have continued to underinvest in the public transport sector. Their focus has rather been on constructing more roads and retrofitting existing ones—which also serve political and other purposes (Obeng-Odoom, 2013). The problem, however, is that road construction may be one of the few cases in which Say’s law, supply creates its own demand, applies. The construction of more roads in Ghana has encouraged the importation of even more old cars, which end up worsening the safety problems in the country (Obeng-Odoom, 2010, 2013). Per the foregoing, as summarized into Fig. 1 below, it could be argued that road accidents (but road transport problems in the broadest sense) in Ghana primarily are due to a high dependence almost exclusively on cars–either as owners or as passengers, in the context of the failure of the state to invest in alternative forms of transport, in which exploitative relationships between drivers and car owners as well as police corruption and land-use patterns-induced traffic congestions play key roles in reinforcing the prevalence of driving practices that undermine safety imperatives.

Fig. 1

Conceptual framework of influences of road trauma in Ghana.

Thus, at the heart of Ghana’s road transport safety challenges are how the confluence of the programs and ideologies of foreign powers and the profiteering and political interests of powerful private groups and public officials undermine investment in public transport systems, leading to a high dependence on a privately run, deregulated commercial passenger transport industry that is structurally embedded in exploitative power relations that incentivize or induce adverse driver behaviors. Ghana’s road safety problems including adverse driver behaviors such as over-speeding, fatigue driving and the likes need to be understood against the backdrop of the land-use patterns as well as the structural conditions of scarcity, deprivation, inequalities and the exploitative labor relations resulting from how foreign powers and powerful local private and public interest groups have molded and entrenched the road transport sector in its present form to serve particular purposes. Whether or not the structural conditions of scarcity, deprivation, inequalities, exploitations and realities of contested power relations that create, and, indeed, maintain and worsen road safety challenges such as risky driving practices and their deleterious consequences in the country are amenable to law enforcement measures—the preferred safety strategies in Ghanaian policy circles—is the concern of the next section.

Source link : https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-020-00695-5

Author :

Publish date : 2021-01-14 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.