As multiparty democracies come under increasing pressure around the world, West Africa has emerged as a bright spot. In recent years, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Sierra Leone have successfully used elections to help recover from civil conflicts. Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal have experienced peaceful transitions of power between competing political parties. And just last month, Gambia, mainland Africa’s smallest country, ousted a longtime tyrant, Yahya Jammeh, and installed a democratically elected president, Adama Barrow.

Foreign governments and international institutions should heed the lessons of Gambia’s transition for other countries struggling under autocratic rule. They should also support the new Barrow government, which has taken over a nation crippled by chronic mismanagement and corruption and is in dire need of economic and political support.

HOW JAMMEH FELL

Jammeh had ruled Gambia, a sliver of land mostly surrounded by Senegal, since July 1994, when he seized power in a coup. Over Jammeh’s 22 years in office, his rule descended into despotism and farce: he routinely tortured and jailed his critics, fancied himself a global Islamic leader, and even claimed to have mystic powers, creating “cures” for infertility, diabetes, and HIV/AIDS. Jammeh’s brazen corruption funded the purchase of expensive properties around the world, including a multimillion-dollar mansion in a Maryland suburb of Washington, D.C.

Before the December 1 election, a coalition of Gambia’s opposition politicians came together and chose Barrow as their candidate—the first time they had ever unified behind a single contender for the presidency. As the results trickled in, it became evident that Gambians had had enough of the abuse and intimidation that had previously worked in Jammeh’s favor. But Jammeh, after initially conceding defeat to Barrow, refused to leave office, citing what he claimed were “abnormal irregularities” in the results. Jammeh’s domestic support quickly unraveled, as senior officials and organizations—including the country’s electoral commission, bar association, and press union—publicly called on him to step down. His regime’s typical tactics of fear and repression were fueling dissent instead of stifling it.

ECOWAS soldiers on patrol near the border with Gambia, Karang, Senegal, January 2017.

Thierry Gouegnon / REUTERS

As foreign governments and regional organizations began to back the election results, the pressure on Jammeh to give up power mounted. The African Union and United Nations voiced their support for Barrow, and the Economic Community of West African States came out quickly and firmly in support of his victory. In January, the leaders of ECOWAS member states went to Gambia in a series of attempts to convince Jammeh to back down.

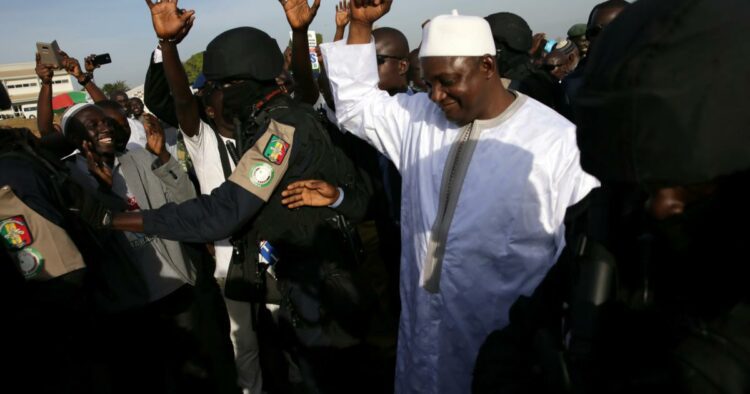

The diplomatic pressure was effective largely because it was compounded by a credible military threat. A few hours after Barrow was sworn in as president at the Gambian embassy in Senegal on January 19, a coalition of forces from five ECOWAS countries entered Gambia, stopping short of the capital to allow a final diplomatic push for Jammeh’s exit. Jammeh finally left Gambia for Equatorial Guinea on January 21, after looting the state’s coffers and loading his luxury cars onto a Chadian cargo plane. Last week, Barrow returned to Gambia from Senegal to begin rebuilding the country.

BARROW’S BURDEN

Gambians are understandably optimistic about their country’s prospects, but Barrow’s government faces some daunting challenges. For more than two decades, Jammeh ran Gambia as a mafia state, letting its economy founder as he enriched himself and his family. As a result, Gambia is the only country in West Africa whose GDP per capita has suffered a net decline since 1994: the average citizen is nearly 40 percent poorer today than he or she was when Jammeh came to power. After decades of erratic, predatory rule, the new government must reconstitute the basic institutions of the state and the economy.

The good news is that outside actors can help set Gambia on a stable, prosperous path. The first step should be for the International Monetary Fund, the African Development Bank, and the World Bank to provide emergency grants and loans to the Barrow government. Although Gambia’s poverty rate is around 50 percent, international financial institutions should treat it less like a typical low-income borrower and more like a postconflict country bouncing back from national trauma, since the scale of its economy’s deterioration is so great and the window of opportunity to address it is narrow. Those organizations should tap into their funds for fragile states, which would let them rapidly inject much-needed cash into Gambia and begin projects with immediate results, rather than spending months drawing up detailed plans. An overly cautious approach from donors would waste the opportunity presented by the political transition and could even raise the risk that the political coalition that has just come into power will unravel. Gambia is small enough—its economy is worth less than $1 billion—that such an approach would not require much money or indeed any new pledges on the part of donors. The existing resources of international institutions are more than enough to help get the country’s basic services up and running again, reinvigorate tourism, and ease private investment, especially from the Gambian diaspora.

Second, the United States and the World Bank should help ensure that the money stolen by Jammeh’s government returns to the country. Local authorities are already examining allegations that Jammeh smuggled millions of dollars out of the country. The U.S. Department of Justice should assist Gambian officials in that investigation and with additional asset recovery efforts that will be needed in the coming years. Jammeh’s mansion near Washington, for instance, could likely be seized on anticorruption grounds. The FBI and the World Bank have technical assistance programs that help states retrieve public funds looted by dictators; they should use those programs to support Gambia’s democratic transition. Seizing Jammeh’s ill-gotten gains and returning them to Gambian citizens—their rightful owners—would set an important precedent and help hold Jammeh’s government accountable.

Former Gambian leader Yahya Jammeh boarding a plane to leave Gambia, January 2017.

Thierry Gouegnon / REUTERS

The international community should also support the establishment of a truth and reconciliation commission, which Barrow has identified as a national priority. Jammeh’s long rule divided the Gambian populace along religious, ethnic, and political lines, deepening dangerous social fissures. These cleavages remain latent for the moment. But with Jammeh still in the region, the possibility of his allies meddling in Gambian politics and potentially inciting discord remains. A state-sponsored process of social healing would help mend Gambia’s long-torn social fabric. Similar efforts in the region—in Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia, for instance—have helped consolidate democratic gains and unite previously divided populations. As part of this process, the option of prosecuting Jammeh and former government officials should remain on the table. Human rights activists and ordinary citizens in Gambia seem to be overwhelmingly in favor of Jammeh facing trial. Healing the collective trauma of Jammeh’s rule is essential for Gambia’s short-term stability and its long-term prospects.

THE COMING HARMONY?

Gambia’s transition from dictatorship to democracy might provide a blueprint for other democratic movements across Africa. A united political opposition, active regional support, increased media attention and public advocacy, and a vocal diaspora all came together to bring down one of Africa’s longest-serving autocrats. Those factors could help spur democratic progress in other countries, too.

As popular support for democracy continues to rise across the continent, other regional groupings should follow the lead of ECOWAS and support citizens’ aspirations in their own neighborhoods. Consider the contrast between ECOWAS and the 15-member Southern African Development Community: after the Zimbabwean leader Robert Mugabe lost an election in 2008, SADC never enforced the results. Instead, regional leaders coerced the opposition into a flawed unity government that merely provided cover for Mugabe to retain power, thus cementing a dictatorship at the expense of ordinary Zimbabweans. Mugabe, now 92 years old and in power for 37 years, plans to run again in 2018. West Africa’s firm stand in support of democratic principles in Gambia should make it harder for SADC and other regional bodies to continue to enable discredited autocracies.

In 1994, the year that Jammeh’s reign of terror in Gambia began, the author Robert Kaplan wrote “The Coming Anarchy,” a popular essay that predicted that the chaos then plaguing Sierra Leone could sweep across West Africa. That prediction proved to be wrong: thanks to Jammeh’s electoral defeat, democratically elected governments now lead every West African nation. Foreign governments and international organizations should work to preserve that momentum, in Gambia and beyond.

Loading…

Source link : https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/gambia/2017-02-02/gambia-stands

Author :

Publish date : 2017-02-02 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.