Embed from Getty Images

This is part of a series of interviews with experienced organizers and movement thinkers on ways to defend and expand democracy amidst the rising authoritarian tide globally.

The recent election in South Africa reminds us that a genuinely free election is still a relatively new thing in that country. Not long ago South Africa was a textbook case of a minority oppressing the majority and using its government to enforce it.

One of the student leaders of the 1980s democratic revolution in South Africa was Janet Cherry. While leading university students into successful struggle against the apartheid regime, she was recruited into the African National Congress, or ANC, and built alliances among student organizations and trade unions. They found the consumer boycott to be among the most effective macro-level tactics for forcing change, as it targeted the corporate sector which, in turn, had major influence on the political regime.

During the struggle she was harassed and her car firebombed. She experienced death threats and was imprisoned multiple times for as long as two years, including a period of solitary confinement.

As the conflict generated by the movement increased, Janet strategically used vision to bring people over to the side of multi-racial democracy. When the anti-apartheid movement necessarily increased conflict and turmoil, she took part in organizing that went into white communities and held meetings to help them envision a future where peace was in their daily lives. The group process led white South Africans to realize that this future could be had by giving up apartheid.

In this interview, Janet shares important lessons from the grassroots movements that took on the authoritarian regime and the personal impact of her life as an anti-apartheid organizer facing a high level of violent repression.

You began your activism against apartheid as a young college student. How challenging did racism look to you at that time?

Janet Cherry

I was in a little bit of a bubble, because segregation was almost absolute. In the 1970s, I grew up going to an all white school, living in an all white neighborhood. Everything was segregated, and the only Black people we knew were domestic workers. My parents were liberal, and I was exposed to the injustice of what was going on. But it really wasn’t a case of being exposed to racism, because we actually didn’t even have any contact with Black people. It was really that level of segregation.

I came into activism in the beginning of 1980 as a first year college student. What drove me was the workers movement — the Black workers struggling to organize independent trade unions. My first experience of political action and of nonviolent direct action was my boyfriend telling me about how he engaged in what we call a trolley jam, where you go into a supermarket and you fill the supermarket trolleys full of this product. Then you take it to the till and block up the tills and say, “I can’t buy this. This company is discriminating against the Black workers, and they’re being treated unfairly.” You cause a big disruption in the store. I was still in high school at that time, and it just really made such an impression on me. I thought this is really where the struggle is at.

I decided to join the Wages Commission, which was involved in this kind of support for worker organization. Just by chance, there was a huge strike of the workers in the meat industry. They had also formed a union — an independent union — and were struggling for recognition. I got drawn into this community committee to organize a consumer boycott of red meat, which was right across the Cape Peninsula in all communities, Black and white. It brought me into contact not only with trade unions, but with Black youth and student organizations, community organizations, and so on, which was extraordinary because we were in a completely segregated society.

The main universities — like the University of Cape Town where I went — were white universities. Black students could only attend them with special permission. So we got involved in the struggles around education — not just the workers struggles — and set up a sort of alliance between the white university student organization, the Black university student organization and the Black high school student organization, which was immensely powerful at that time. Together with the meat strike committee, we had this massive student organization. We started working quite sensitively with Black student organizations, being very self-conscious about how to organize white students and their concerns, while at the same time trying to build relationships with the Black student organizations and Black trade unions.

I’ve got to say, [there is some important context for this situation]. The 1970s was the era of very harsh repression and police state. In the midst of that, came the growth of the Black consciousness movement with Steve Biko. That movement was brutally suppressed in 1977. Biko died in detention, and all the organizations of that era banned. It took a few years before there was something of a resurgence, which took the form of what we called the Charterist movement, based on the Freedom Charter. It was essentially the liberation movement asserting nonracial politics and a sort of inclusive politics. So that was the context in which the Black and white student organizations started working together.

Embed from Getty Images

How important were young people to the overall success of the movement?

I think it was very important because there was an older generation of activists who were effectively suppressed in the 1960s. Many people went into exile. So when we became adults, we were the youth generation of the late ‘70s and ‘80s. I think we had to sort of pick up the baton and start a new way of building up a movement. There were a few old people around, but they were scared because they had been so thoroughly repressed. We sort of drew on their wisdom and history, and realized we actually had to build a movement inside South Africa. We had limited contact with the liberation movement in exile, which very importantly generated the whole international solidarity movement. But we, as young people, didn’t have contact with that. We were trying to work out new strategies and new ways of doing things.

As a white person in a larger movement composed of people of color, did your privilege ever become a liability? Were you ever discounted in terms of your participation in the movement against apartheid?

No, and I think it was partly because of the moment at which I got involved, which was when the position of non-racialism, or inclusiveness, was being asserted quite strongly. We were very conscious of white privilege. It wasn’t just a perception. In apartheid South Africa, it was a legislated reality.

We tried to use our white privilege to do things that were not accessible — for example, working with township organizations. I had access to a printing press at the university, and I had access to a car. I could print pamphlets and drive them to the township and distribute them. Those kind of resources were not accessible to most people.

We had to think quite carefully and be very conscious of not dominating. We had a principle of Black working-class leadership. So we said, “Okay, we have to know when to step back and not always use our education, our access to information and so on to dominate.” That was quite tricky, but I felt included. I felt that the majority of Black activists were extraordinarily generous.

Sign Up for our Newsletter

It’s easy to imagine that an authoritarian government is all powerful, with its eyes everywhere. Did you sometimes feel that way?

It depended where you were. It wasn’t a totalitarian state in the same sense that some totalitarian states operated. I’m thinking of what I know about East Germany, for example, where everybody was spying on their neighbors. It wasn’t like that. However, once you were identified as an activist — and especially if you had any links with the liberation movement or were suspected of having links with the ANC — there was a high level of surveillance.

It’s useful to think of the different layers of activism. Thousands of students at the university would participate in meetings or protests, and they wouldn’t be under surveillance. If they were involved with a particular protest, where they broke the law and were arrested, then they would immediately be put on some kind of list. Then, if they became committed, were consistently involved and moved into the leadership of student organization, they would then go up into another level of surveillance, where security police would keep an eye on them. They would infiltrate all the movements, of course, and have their spies who would report to them on who was doing what, who was moving into the leadership.

In the mass movements, you would have a layer of leadership and then there would be another layer of people who were sort of semi-clandestinely in the leadership and in contact with the liberation movement. They would be under the most surveillance. During a state of emergency or times of repression, they would be taken out and put in detention so that they couldn’t be active, just as a way to paralyze the movement. Of course, there were also cases of assassination and disappearance, where the people identified as the key activists were actually abducted and murdered.

For all the brutality of the apartheid state, it was selective. It generally tried to work within the law. It wasn’t a military dictatorship, and they always had a justice system. People were brought to court, except if they were under security legislation, in which case, like in Guantanamo Bay, they could be held for a year in solitary confinement without trial and accused of terrorism. That was the most serious form of detention, where the sort of rule of law just fell away. Otherwise, though, they sort of operated within the rule of law, which meant there was room to do things — to organize.

Could you give examples of the kinds of repression the regime used against you?

After being at university, I moved to Port Elizabeth, which is an industrial city, where I started working with trade unions and local organizations — what we called civic movements, township organizations and women’s organizations. There was a lot of informal harassment because I sort of stood out. I was this young white activist who they identified as this University of Cape Town-red-Marxist-radical-whatever coming into this environment and doing this kind of work. Harassment took the form of intimidation: sabotaging vehicles, throwing rocks through windows, that kind of thing. When we were engaged in mass action and public action, the police had riot police — what they called the reaction unit — which used tear gas as a first method to disperse crowds. Then they would use rubber bullets, and then once things really became intense, by early 1985, they were instructed to bring the townships under control by all means necessary. They used live ammunition and actually killed people at funerals. So, it was an escalation of violence.

One of the interesting things we did was engage in attempts to try to contain that violence. I didn’t organize it because I was quite young at the time, but the older women — Black and white woman together — organized to manage one of the funerals of the youth who had been killed by police. They said, “We’re not going to allow this to escalate into the cycle of violence where somebody is killed by police, we have a funeral, the youth get incredibly angry, they confront the police, and then the police kill another person.” The women decided to break the cycle by running the funeral themselves and being completely disciplined and peaceful in the way they did that. The police confronted us head on, tear gassed everybody and dispersed the crowd, but I think we did prevent further deaths in that case. It’s hard to know whether that was really effective in the long run, but I think it was important to try and take some kind of action against the repression.

By mid ’85, there was the first state of emergency, and the police in the city were particularly brutal. They tortured the leadership of the mass movement, which were mainly the township leadership, and they assassinated the key leadership.

They thought that they had brought it under control, but by early 1986 people had started reorganizing and building up at the grassroots level. So, things escalated again, and there was another state of emergency, resulting in widespread detentions, like thousands and thousands of people. They detained the youth who were just involved in protest and street level actions for two weeks, often beating them up or torturing them before release. Then the middle level leadership, which included me, they detained for between a month and six months. The key leadership were detained for up to three years without trial. So that was just a method of trying to bring things under control by taking people out of that environment.

Support Us

Waging Nonviolence depends on reader support. Make a donation today!

Donate

That would be a scary time for many participants in the movement. I’m wondering how you handled your own fear because it clearly didn’t stop you.

I can’t say I’m a fearless person at all. I was very scared, but there was an enormous sense of conviction of the rightness and the inevitability of our cause, you know? That maybe speaks more to resilience. Sitting for months and months in detention and being released — and then detained again and released and detained again. There was a sort of feeling of: “History is on our side. We’ve just got to grit our teeth and hang on.”

It’s quite bizarre to say this, but there were times when I actually felt safer inside prison than out of prison. Because if they didn’t actually want to kill me, then the prison was an environment where things were at least contained. The prison authorities were different from the security police. If the security police wanted to assassinate you, they probably would. If they wanted to interrogate you and talk to you for information, then they would do that. But they wouldn’t do that to anybody. They would have needed an informer or some information that exposed your involvement with the ANC or some kind of underground activities. Because of my white privilege, and because I was quite well known, they were cautious about doing that. So, in a way, I was protected, but other friends of mine weren’t.

Ultimately, I think a lot of the dealing with fear is through community and being part of a group that supports each other. It’s about not only having that sense of personal conviction, but having a network around you. In Port Elizabeth, the number of white people who were involved was very small. There was a slightly bigger group of people who were sort of white liberals who were involved with human rights — and they were really important because we knew they were there as backup. There were lawyers, human rights activists, journalists, church leaders and so on. They were a sort of layer of people who were outside the core of activism, but were able to provide a kind of monitoring and support role.

Sometimes when an authoritarian regime engages in repression, there’s a boomerang effect, in which even more people join the movement out of fear, anger and determination. Were there such times in South Africa?

Definitely. This happened after September 1984’s Sebokeng uprising. There was a process of escalation, where more and more people got drawn into the struggle as it spread to townships across the country. As the regime used increasing levels of violence, including things like detaining young children, the apartheid state started to become de-legitimized. In the white community, the regime threatened them with this fear of the Blacks and the communists taking over and all this kind of nonsense. In response to repression, the movement worked to convince the white population that it had a place in the society, the future. That allowed white people to feel that they were not under threat from the Black majority or from the movement.

There was a very harsh control of information. Many people in the white population didn’t really know what was going on. There was a state of emergency, the newspapers were censored. I remember hearing people say “There’s no smoke without fire,” meaning they wouldn’t be detaining people unless there was something they were involved with. But there was a point at which that was broken through — and the brutality of the regime was so apparent and the response and resistance so widespread that it became impossible to ignore. More and more white people began to perceive the amount of violence that was going on and realize it was getting almost out of hand or problematic for them.

Embed from Getty Images

Did you have missionaries reaching out to white people to point out what was going on and to try to get through the otherwise cloaked nature of the repression?

There were important initiatives that happened on different fronts. The church played quite an important role. Albert Nolan [a white Catholic priest] put together the Kairos Document, calling for a moment of truth where Christians had to understand what was going on in the society. There was also the Institute for Democratic Alternatives for South Africa, which was specifically designed to take groups of white influential people to meet with the liberation movement and just be exposed to ideas and start looking for a way forward. That was quite significant, because white people, even within the regime, hadn’t had contact with the Black leadership before.

It wasn’t always easy. Remember, in the student movement, we felt that we had a responsibility to work within our own constituency. In fact, Steve Biko said this to the white student leadership. He said, “You’ve got to organize yourselves. This is your responsibility, this is your mission.” We thought the most important way to do this — which I think has a strong correlation now to Israel — is in military conscription.

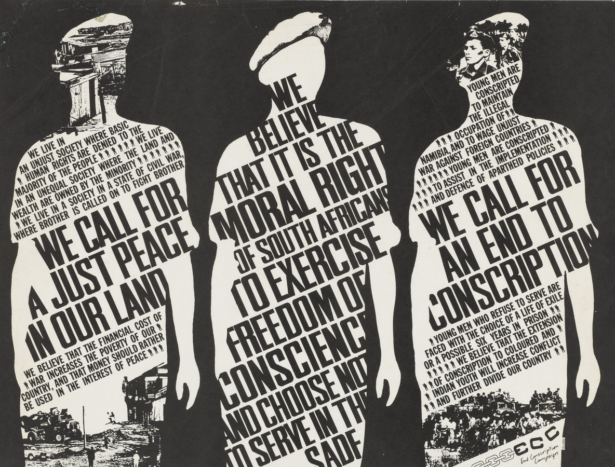

In South Africa, only white men were conscripted. So it was a completely racist army, which was being used not only in South Africa, but in Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, etc. We identified that as the one area where young white people had to pay quite a heavy price for being privileged. They had to spend two years in the army, and then they had to go and fight these wars in other countries, like Americans did in Vietnam. We drew quite a bit on the Vietnamese antiwar movement in the United States. We even had a poster, which was called “Angola, South Africa’s Vietnam.”

We had a whole youth culture, which more related to white youth in terms of the kind of music they would listen to in those days, with a strong anti-establishment, anti-military theme. We built up this End Conscription Campaign to effectively undermine the military and its legitimacy among the white youth to try to get them to defect.

End Conscription Campaign poster

End Conscription Campaign poster

In addition to being an amazing organizer and activist, you are also a trainer. What were some of the ways that training paid off for the anti-apartheid movement?

We were using Paulo Freire in trainings and work with community and labor organizations. We used it as a pedagogy to get people to think about their situation, their oppression and how to analyze it. We gave people access to information about the law, what their rights were, how to run a protest, all these kinds of practical information. I ran a crisis center, helping people with paying bail and finding lawyers and where people were detained. Then we also ran worker education and women’s education with groups that were combining practical knowledge, including life skills, language skills and numeracy skills for adults, together with things like history and organization, and so on. We were sort of putting together the content with something that was useful for people.

I hear so much creativity in your movement. Would you say that was true?

It was definitely true, and I think the creativity came from a whole lot of different angles. You had white university students trying to find ways to work with privileged white youth who had to go to the army, and they were using particular kinds of music, culture and ways of doing things that were creative. In a Black township organization, there was a whole different culture, which involved mass singing and the conversion of hymns into struggle songs. There was a lot of tactical creativity around things like consumer boycotts and ways of responding to repression.

The ANC’s slogan was “Make the country ungovernable, make apartheid unworkable.” So it was a program of actually calling for complete destruction of government structures and delegitimization of government, which can be quite dangerous. But actually, in a very limited way, in certain townships, people were able to actually take control of their own lives and areas. We had all kinds of very pure anarchist ideas, saying, “We want to control all aspects of our lives. Democracy is not just about voting.”

But it didn’t go as far as having any real economic control. The furthest I think that we went was with the consumer boycott in the townships. I don’t know if you’ve seen the “A Force More Powerful” documentary and the episode on the South African consumer boycott. Mkhuseli Jack explains how they they took up this boycott of the shops in the white areas as a way of putting pressure on the white elite to, in turn, put pressure on the government to meet various demands. They were able to do that because they had townships shops, which were able to supply certain goods — and they warned them in advance and said, “Okay, now you need to stock up in preparation for this consumer boycott action.” It was a quite sophisticated and very effective tactic, but it did require some level of economic preparation to sustain it.

I was active in the anti-apartheid movement in the ‘80s — our solidarity version in the U.S. So it’s wonderful to get more of a window into what you were doing over there while we were doing whatever we could here.

Do you know the ANC’s overall strategy, what they call the four pillars? So they said — well, I could say “we,” but it’s still very contentious for me how they understood the relationship between those strategies. Anyway, they said:

1. We are engaged in an armed struggle, but that armed struggle is dependent on mass mobilization.

2. We need the masses to be mobilized and politicized because you can’t run an armed struggle in isolation.

3. We need international solidarity as another critical arm to impose pressure on the apartheid regime.

4. We need an underground, which actually links those three things together. Otherwise everybody is acting in isolation.

I’ve published an article about this, and I don’t think it was strategic coherence. The thing that still worries me is that there is this romanticization of armed struggle. When I look at it in practice, I think the over emphasis on armed struggle was actually detrimental. I would say it’s very costly, and yet it’s very difficult to make that argument when people have invested not only their energy and resources into armed struggle, but their lives. You can’t really question that and say, “Hang on, was this really the right thing to do?”

But in practice, I don’t think it was strategically coherent. As I’ve engaged further in the sort of strategic nonviolence literature and thinking about it, I think it actually in some ways was a detraction from the building of a really strong democratic organization. It also invited repression, which escalated the violence.

I’m so glad you said that. As a pacifist, I automatically become very skeptical about armed struggle. But I don’t make a practice of trying to tell movements what to do. When my opinion is asked, I raise the questions, and for you to make that statement is really important.

I still find it challenging. It’s quite easy to think about things at a tactical level: local struggles, how we organized what we did, how we identified particular targets for action and how we engaged in quite successful campaigns, etc. But I find it more difficult to think about the bigger picture and what was effective.

I haven’t talked about the United Democratic Front, which was really the big movement that I was involved with. That was in response to the apartheid government introducing a reform, which was to give minority groups of [mixed race] and Indian people representation and government, but very limited representation — and it excluded the African majority. This was actually the trigger for the mass movement. We were able to mobilize around this in such a way that it tackled all these issues of the basic democratic demand for “one person, one vote” and for common citizenship. It also allowed us to assert non-racialism, which meant we weren’t going to accept being divided into different racial groups, and to contest what they called Black local authorities in the Black townships, which were undemocratically-elected councils responsible for implementing apartheid and repression. The combination of all those things really led to a complete delegitimization of the regime.

Embed from Getty Images

We drew a lot on Antonio Gramsci for strategy and said, “We’re building a counter hegemony.” The apartheid regime and all these little puppet governments and structures were just not democratic. They were not meeting the fundamental demand, which was “South Africa belongs to all who live in it.” No government can claim authority unless it’s based on the will of the people. The people shall govern. This was the Freedom Charter, which we posed as a clear alternative, as a positive alternative — and it gained majority support. It was really important that we had a positive alternative and that we were putting forward a vision of what’s needed. We could unite everybody around it, so it wasn’t an exclusive thing for this little group or that group.

I don’t know about the United States, but I think if you look at Israel and Palestine today, the premise that there’s a place for everybody — common citizenship, everybody has the same rights — it doesn’t sound that radical to me. It sounds like a normal democracy, and South Africa was putting that forward and saying, “This is the bottom line. This is not madness. This is what we all ascribe to.”

Is there anything you’d like to share about the recent elections in South Africa?

There’s positive and negative. The positive is that, firstly, I don’t think it’s a disaster that the ANC lost the majority for the first time in 30 years. I think it’s actually quite healthy for democracy. It is, in some ways, evidence that we have a resilient democracy, where we’ve got a majority party liberation movement, which has given a path through the democratic process and been forced into a government of national unity, as they’re calling it, with the other parties, including the liberal opposition.

However, it remains to be seen if the government can be effective, because the danger is that it becomes paralyzed without a clear majority and smaller parties vote against things and don’t allow them to go through. The thing that worries me more is that there are parties that have emerged — with seats in the executive now, including the Patriotic Alliance — who are really reactionary and xenophobic. They campaign against foreigners and have these anti-immigrant policies.

While the United States also has strong anti-immigrant sentiment, you don’t have anything like the levels of unemployment that we are facing. Also, [you don’t have] the levels of desperation in neighboring countries. In Zimbabwe and Malawi, people are starving at the moment. Further north, in Mozambique, DRC and South Sudan, there are some of the worst war-wrecked countries in the world. Millions and millions of people are being displaced at the moment. I heard yesterday that, in the DRC, seven million people have been displaced. So, we face, regionally, a huge challenge.

South Africa happens to be the strongest economy in the region. For all the problems, we actually do have a stable government and a rule of law. There’s no danger of warfare. We have to cling to that. It’s really critical that South Africa sustains and is able offer assistance to other countries in the region. That’s my big worry at the moment.

Source link : https://wagingnonviolence.org/2024/07/from-apartheid-to-multi-racial-democracy-lessons-defeating-authoritarianism-south-africa-janet-cherry/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-26 19:33:21

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.