The Egyptians have long denied the serious nature of the situation because they were driven by an historical syndrome stemming from their costly intervention in Yemen in the sixties.

The Turks preceded the Egyptians to the Horn of Africa. At the height of the Turkish proclivity for muscle flexing, that is, before economic realities dawned upon President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and forced him to reconsider his regional calculations, the Turks had reached Sudan and Somalia.

With the Sudanese, they planned to establish a naval base in Suakin order to secure a foothold on the Red Sea. With the Somalis, they found the ground laid for them by previous Qatari political and financial activities. The Turks used their presence to pressure the Emiratis there, then to incite the Somalis to turn against them after years of Emirati support for the nascent security forces in Somalia.

Because he overreached his country’ abilities, Erdogan found himself compelled to shelve the Suakin base project and was content with a more modest relationship than the initial alliance he initially envisaged with the Somali government.

The Turks and the Somalis discovered that opportunism does not make for a long-term policy. As soon as tensions between Doha and its neighbours subsided, opportunist Turks and Somalis began to wonder if their relationship served any purpose whatsoever.

For some reason, the Egyptians have decided to re-enact the Turkish scenario. Instead of seeking a Suakin base in Sudan, they have headed for Eritrea, using the same lexicon from the relationship between Turkey and Somalia. They have sought to substitute themselves for Turkey by stationing Egyptian forces or advisors on the ground and delivering arms to support the Somali forces in the hope of entrenching Egyptian influence or gaining the initiative in the face of the Ethiopians. Cairo somehow believes it can succeed in the Horn of Africa where Turkey failed.

Most certainly, the Eritreans are different from the Sudanese. Many accusations can be levelled at Sudanese military leaders. Their role is one of the reasons for Sudan’s catastrophe. But all Sudanese leaders, since the time when their country was under the Egyptian crown, have never started any initiative without taking into account Egypt’s situation and its stature.

Even Islamists who infiltrated the Sudanese army have acted as if Egypt was part of the spoils they stood to reap, if and when they acceded to power. These are the same Islamists who brought new types of disasters upon their country, leading it to be divided and mired in all kinds of wars.

The Eritreans are different kinds of politicians, especially when it comes to their eternal leader Isaias Afwerki. This former revolutionary sees himself and his country as the centre of the universe. To this day, he has not dealt with anyone nor any country, since the days of the war of independence from Ethiopia, except within the logic of betraying his friends and backers.

There is no country in the region that did not support the Eritrean liberation movement in the seventies and eighties. But all these countries were rewarded with ingratitude. Afwerki is the embodiment of opportunism and betrayal. Perhaps this is what made everyone, except the Israelis, deal with him with the utmost caution. There is no reason to believe that Afwerki’s political logic has changed while he makes his overtures to Egypt and pursues what looks like an attempt to form an alliance with Cairo in order to antagonise the Ethiopians.

One ought to welcome Egypt’s decision to undertake a reassessment of its strategic position in the region and of the repercussions it faces from developments in the southern Red Sea, Bab al-Mandab Strait, the Gulf of Aden and the Horn of Africa.

The Egyptians have long denied the serious nature of the situation because they were driven by an historical syndrome stemming from their costly intervention in Yemen in the sixties and their interpretation of that intervention as one of the key reasons for their 1967 defeat by Israel.

Since the collapse of the internationally-recognised government in Yemen and the Houthi takeover of the country and the outbreak of war with the Saudi-led Arab coalition in 2015, the Egyptians have tried to steer away from any role in Yemen. But geography is a stubborn factor. They were quickly confronted with the rise of Iranian power in the southern Red Sea as represented by the Houthis.

Egypt has paid the price for the stranglehold enforced by the Houthis against global navigation under the pretext of supporting Hamas during the Gaza war. According to some estimates, the Suez Canal revenues have decreased by half, a huge shortfall for the already exhausted Egyptian economy.

Egypt’s reassessment of its strategy in the Horn of Africa was more than necessary. But to this day, this exercise seems limited to two considerations. The first is to annoy the Ethiopians and pressure them in retaliation for their unwillingness to reach an agreement over the Renaissance Dam and the sharing of waters from the Nile River.

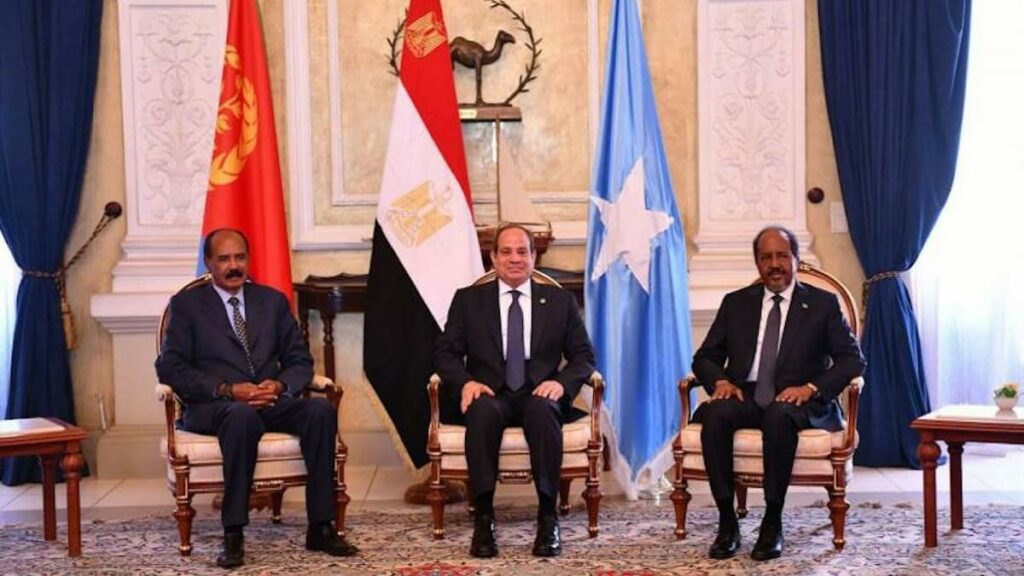

This is evidenced by the visit of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to Asmara and his meeting with Afwerki and Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. This is also reflected by the public statements about security, political and economic coordination, and the implicit discussion of how to pressure Ethiopia.

The second consideration is the decision by the Egyptian leadership to offer unconditional support to the Sudanese army. Yemen has been totally absent from this strategic re-reassessment. What is of concern in the type of priorities underpinning the re-reassessment is the fact that Egypt does not wield the financial and military means to achieve its two goals: to pressure the Ethiopians in order to force them to make concessions on the dam issue, nor to influence the course of the war in Sudan between the army and the Rapid Support Forces.

There is no comparison between the capabilities of Turkey and those of Egypt. But despite that, Turkey has preferred to “withdraw” from the region, whether permanently or temporarily (the oil and gas exploration ship “Oruc Reis” is still on its way to the Somali coast).

Perhaps the geographical proximity between Egypt and Sudan and the historical ties between the two countries have forced Egypt to take sides in the conflict. Egyptian leaders believe the odds of winning the war are in favour of the army chief, Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and not the commander of the Rapid Support Forces, Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. Was it better for Cairo to remain neutral or take sides? Only the outcome of the war will tell us. But Egypt is far from Eritrea and even more distant from Somalia. The distance here is not measured in kilometres, but in means and capabilities.

Egypt does not have aircraft carriers nor big warships that can enforce a tangible presence in the southern Red Sea. It does not have air force mid-air refuelling capabilities that would allow it to brandish its air power where needed. Perhaps the situation would have been different had Egypt joined the Arab coalition in Yemen and secured a foothold there.

The impact of forces that could be stationed on the Somali coast will depend on the logistical support they can receive. This support could be provided by Egypt directly although one has to bear in mind the distance of the maritime supply lines because the Egyptian effort would be very much exposed to both the Ethiopians and the Houthis. The support could also be provided indirectly if Eritrea were to serve as a logistical base for Egyptian forces in Somalia.

Another question is the nature of the enemy that Egyptian forces will face in Somalia. Is it Ethiopia’s tens of thousands of troops stationed there, who are equipped with armoured vehicles and enjoy the logistical advantage of the common borders between Ethiopia and Somalia, or is it the terrorist threat represented by Islamic extremists who will not hesitate to target the Egyptian forces?

The logistical issues, despite their importance, could be the least of Cairo’s concerns if developments lead to a confrontation with Ethiopian forces in Somalia.

The Egyptians would find themselves there in an alien environment which has not been previously scouted by their country’s military intelligence. Things become nearly comical when one sees the presidents of two Arab countries sitting down to talk through an English translator.

How many translators from Swahili, the language of the Somali people, or English, would the Egyptian officers and soldiers need there?

What about the common links between the two countries, namely Egypt and the Eritrea of the betrayal-prone President Afwerki?

Egyptian “intervention” in Somalia is a risky endeavour. Apart from Afwerki, no one seems to support such an involvement, neither internationally nor regionally. Opportunistic Turkey did not shelve its plans for intervention in the Horn of Africa for without a reason.

Haitham El Zobaidi is the Executive Editor of Al Arab Publishing House.

Source link : https://www.atalayar.com/en/opinion/haitham-el-zobaidi/egypt-s-risky-bet-in-the-horn-of-africa/20241018130000206387.html

Author :

Publish date : 2024-10-18 11:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.