In 1974, The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute received a unique bequest of forty-seven prestige caps and headdresses from Central Africa’s Congo River basin. This gift came from Lilly Daché, the French-American milliner whose inventive designs dominated the American and French fashion scene from the 1930s through the 1950s. [1] Among Daché’s gift were several of the very same caps, hats, and headdresses sported by models in photographs by the avant-garde American artist Man Ray featured on the pages of Harper’s Bazaar on September 15, 1937.

Spread of Paul Éluard’s “The Bushongo of Africa sends his hats to Paris,” in Harper’s Bazaar, September 15, 1937. Photography by Man Ray, featuring the model Adrienne Fidelin (right).

Tracing these objects’ long and circuitous journey from the Congo to The Met reveals how they found their way into the Surrealist orbit, spawned a revolution in Western hat design, and came to be showcased in several international publications before arriving at the Museum. This same collection provided the vehicle through which a then-anonymous Guadeloupean dancer and model, Adrienne Fidelin, became the first Black model featured in a major American fashion magazine. As such, the story of these objects and their impact on diverse creative practices belongs to a larger account of colonialism and African art’s influence on modernism.

A selection of Congolese objects from the bequest of Lilly Daché.

Each piece in this diverse range of hats, caps, and crowns was crafted and worn by members of the Bushongo and other groups united under the Kuba confederacy in modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo. Like many sub-Saharan African societies, groups in this region consider the head the most important place in the body, employing elaborate hairstyles and headdresses as forms of personal expression and nonverbal communication. These objects exemplify the rich variety of creative regalia that utilize distinctive forms, materials, colors, motifs, and a variety of accessories to mark the status and initiation of mostly male members into various title-holding societies.

The basis for nearly all headwear in the Kuba confederacy is the laket mishiing, a type of simple domed cap worn on the crown of the head and secured with a metal pin. These small raffia hats are granted to men upon completion of an initiation process that marks their transformation into mature members of Kuba society. Over half of the objects in the Daché donation are identified as this type of hat form. The more elaborate the combination of feathers, shells, animal skins, and beads adorning such unique creations, the higher the status of the society member. The most intricate forms of headdress are reserved for kings and chiefs, constituting an essential component of royal regalia. [2]

Left: Kuba hatmaker, Mushenge, Congo (Democratic Republic). Photograph by Eliot Elisofon, 1971, EEPA EECL 7267, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art Smithsonian Institution. Right: Kuba Nyim (ruler) Mbopey Mabiintsh ma-Kyeen, Mushenge, Congo (Democratic Republic). Photograph by Eliot Elisofon, 1947, EEPA EENG 01144, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art Smithsonian Institution

The prestige caps and headdresses in this collection date from the late nineteenth to early twentieth century. This was a period in which the so-called Congo Free State (1885–1908) was under the brutal rule of Belgium’s King Leopold II, followed by its subsequent exploitative colonial iteration under the name Belgian Congo (1908–60). During this time, agents of the government, explorers, and missionaries forcefully removed or traded these culturally significant objects, which were then sold on the European art market. They are testament to the fact that creative practices of artists and artisans persisted even in the face of the region’s violent colonization and the genocidal plundering of the country’s rich natural resources. [3]

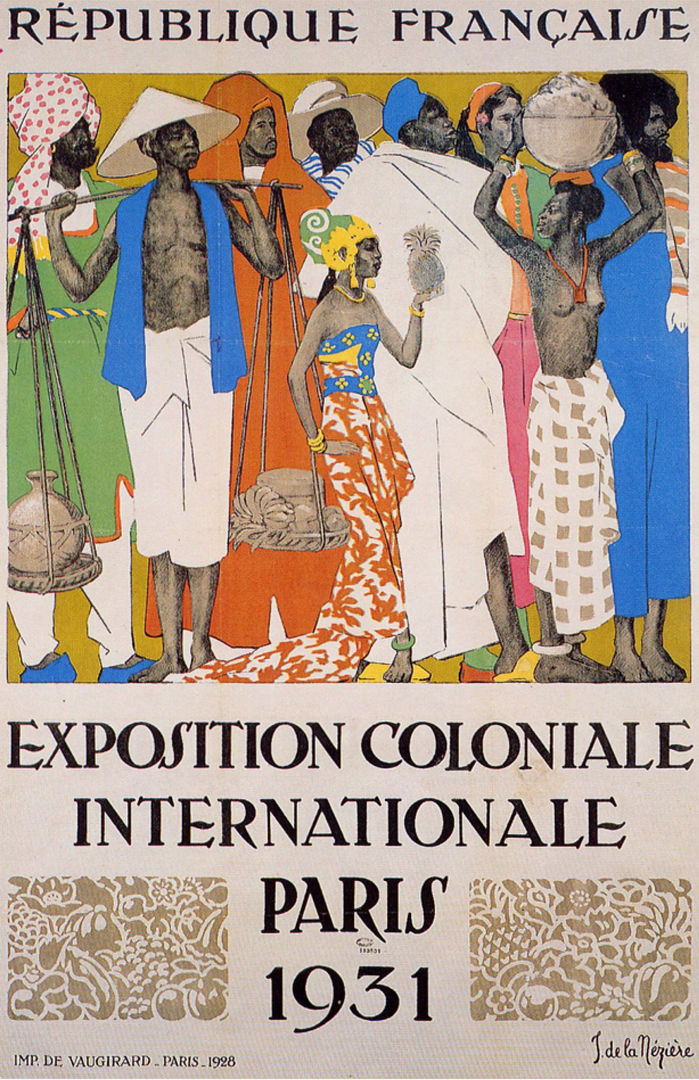

When these pieces left the Congo is unknown. But Lilly Daché’s bequest to The Met places them at the Exposition Coloniale International de Paris in 1931, a provenance that situates the works at the heart of the period’s colonial violence. Accompanying notes identify them as generically “African,” providing no regional, historical, or cultural context; the paucity of documentation relating to the unique histories of these individual creations is a legacy of such colonial practices. But Daché’s claim about the objects’ provenance was actually mistaken. Recently discovered documents—including an invoice for the hats, a photograph, and related correspondence dated February 1, 1937—establish that Ratton acquired them from the Brussels-based collector Raoul Blondiau. [4] Whether or not Ratton shared with Daché this information, or his associated visit to a colonial fair in Brussels, remains undetermined. Making her donation almost half a century later, the milliner may have conflated—unintentionally or otherwise—the 1936 fair in Belgium with the more famous 1931 Colonial Exposition in Paris.

Poster for the Exposition Coloniale Internationale, Paris 1931. Designed by J. de la Nézière

At a time when the rationale for imperialist expansion was under increasing critical scrutiny, the French government organized the Colonial Exposition to justify the country’s colonizing activities and buttress its cultural hegemony. To advance their agenda, the exposition’s organizers promoted a “coloniale moderne” aesthetic. This construct presumed a harmonious melding of foreign and Western fashion and decorative arts that ostensibly represented “collaboration rather than appropriation and a fusion of two cultures rather than hegemonic exploitation.” [5]

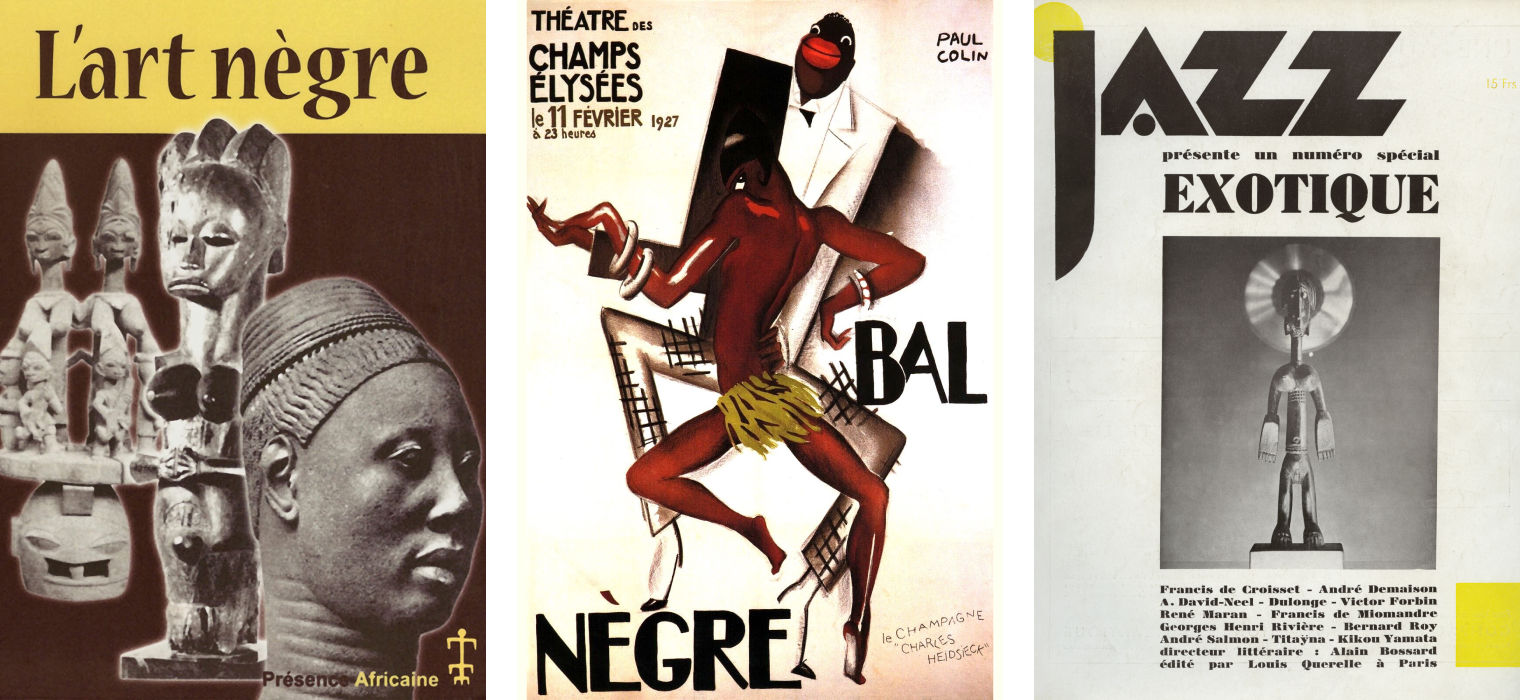

The diverse headwear that originally served utilitarian purposes of personal adornment, status, and ceremonial dress were transformed in the Western context into coveted art and fashion objects emblematic of the thirst for Black culture that flourished in interwar Europe. In France, the fetishization of Black culture under the undifferentiated and fraught rubric of l’art nègre conflated the material culture, creative production, and physical bodies of peoples from the African continent and its diaspora. [6]

The fetishization of Black culture under the rubric of l’art nègre is visible in the time’s posters and publications.

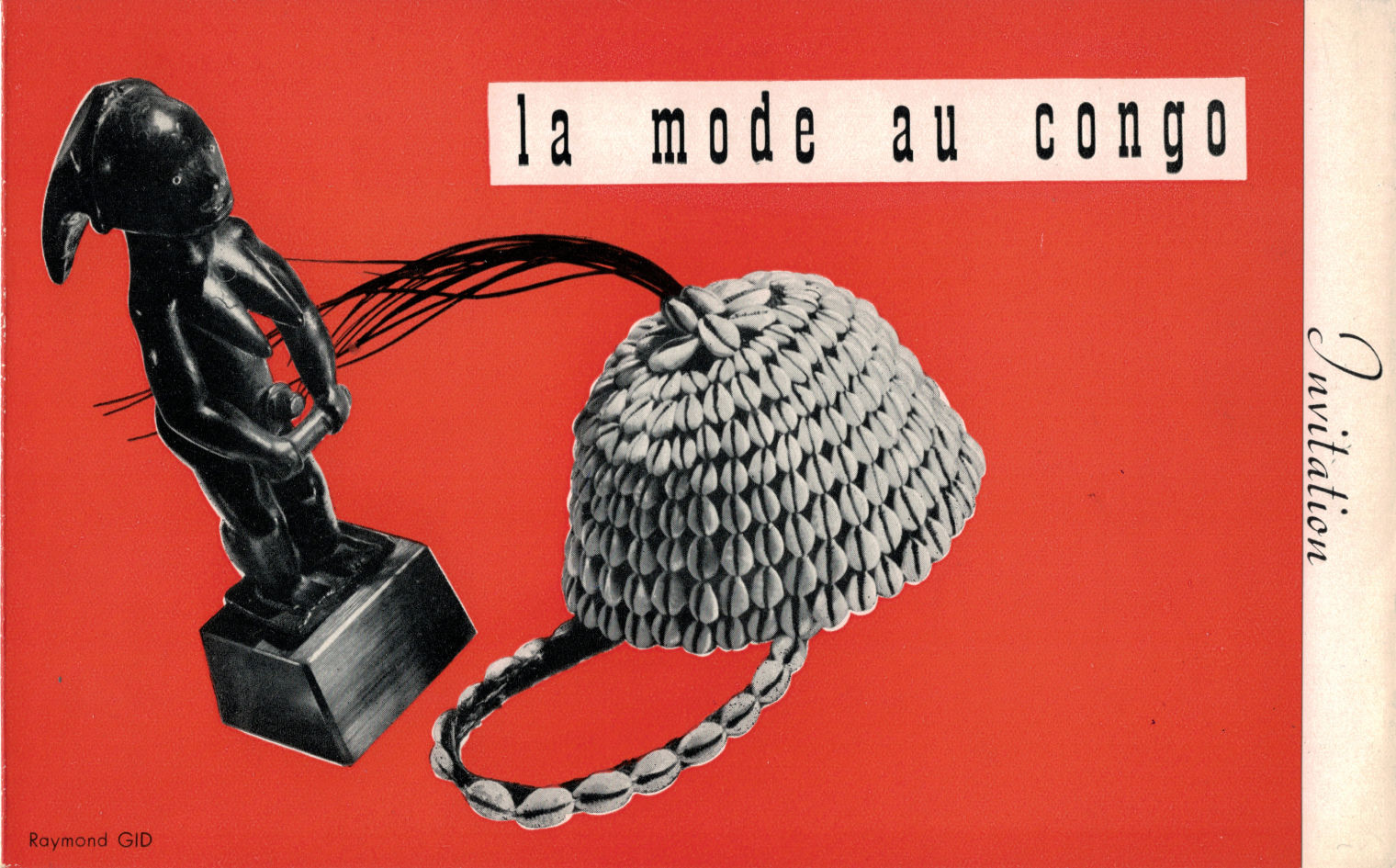

Six years after the Colonial Exposition, the headdresses appeared in the vitrines of the Galerie Charles Ratton in an exhibition titled La Mode au Congo. Ratton, the preeminent dealer in the Indigenous arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas in Paris during the interwar period, was an avid collector of African headwear. Growing up with a father who was a milliner, he was presumably more attuned than his contemporaries to the artistry of the Congolese regalia and more appreciative of their creative value. [7] By the time La Mode au Congo opened on April 29, 1937, the gallerist had amassed an inventory of fifty-two such objects. [8]

Exhibition invitation for La Mode au Congo, Galerie Charles Ratton, 1937. Courtesy Archives Charles Ratton – Guy Ladrière, Paris

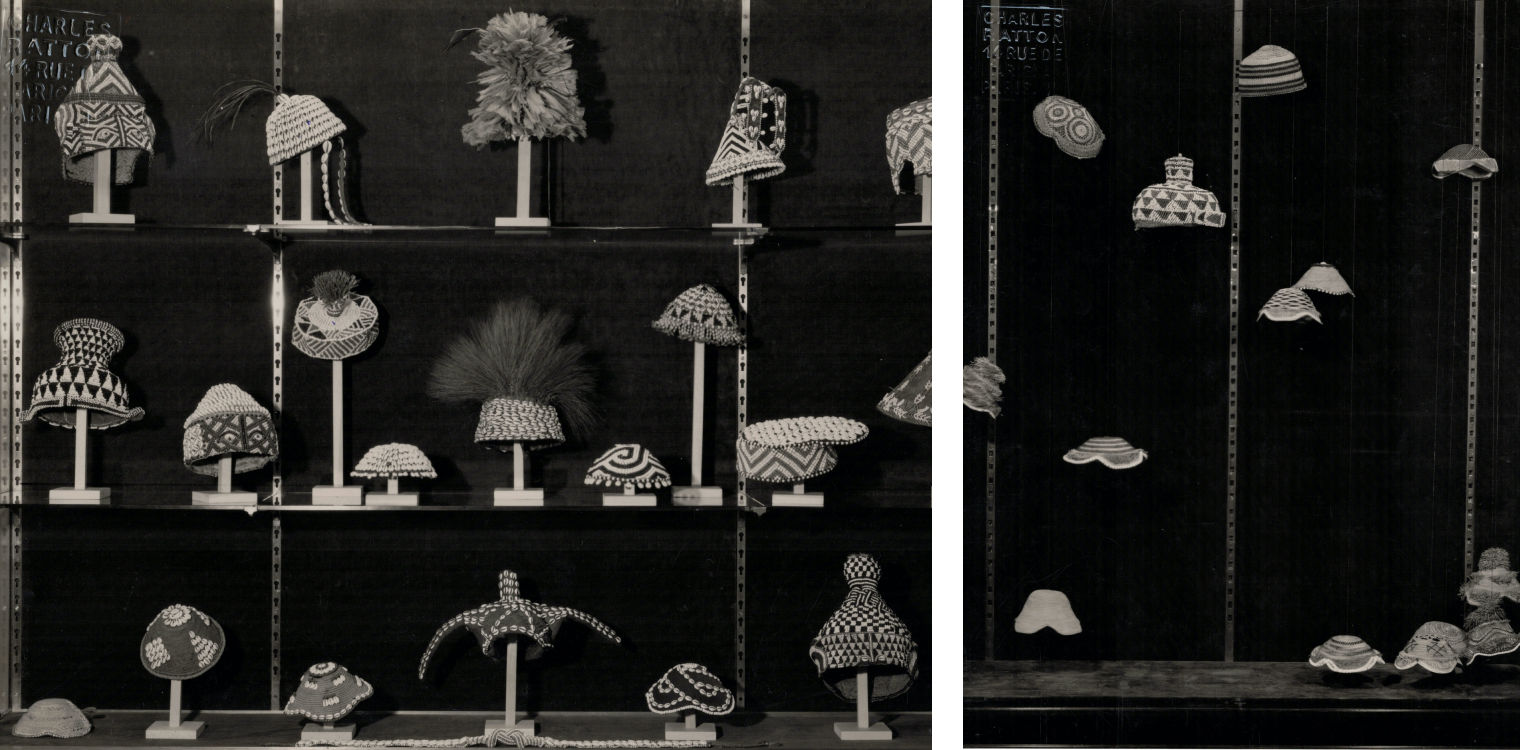

Installation views of La Mode au Congo and press clippings from Ratton’s personal archives are instructive for understanding both the gallery’s approach to displaying the objects and the show’s reception. In one of the gallery’s main vitrines, the objects were deftly installed on individual stands at varying heights in a rhythmic pattern, presented as singular objects worthy of aesthetic reverence. This conventional installation contrasted with the unusual display of the headdresses in a neighboring vitrine. Playfully hung from wire or string at varying heights, they take on the haunting appearance of disembodied flying objects imbued with irrational spirit of the Dada or Surrealist zeitgeist.

Installation views of La Mode au Congo, Galerie Charles Ratton, 1937. Courtesy Archives Charles Ratton – Guy Ladrière, Paris

Ratton was no stranger to the avant-garde practices that were revolutionizing the face of modernism. His relationships and alliances with leading members of the Surrealist movement afforded him a less conventional vision for his gallery, as most notably reflected in his collaboration with André Breton in hosting the 1937 Exhibition of Surrealist Objects. [9] This exhibition’s radical and deliberately disruptive juxtaposition of more than two hundred markedly heterogeneous items—including numerous Indigenous objects from Oceania and the Americas—suggested a modern cabinet of curiosity, but without any discernible logic or attempt at classification. [10] It was as if, Laurence Madeleine observes, “the Surrealists were rejecting any reorganization of a world whose basic reality and rationality they were challenging even more radically than they had with words.” [11]

Appreciation of the utilitarian nature of such objects—rather than a mere admiration of their forms—was underscored by the Mode au Congo exhibition that filled these same vitrines one year later, and by Man Ray’s related photographs of models crowned by the headdresses. Unlike the widely celebrated Exhibition of Surrealist Objects, however, the subsequent show has largely flown under the radar in later scholarship. This contrasts with the exhibition’s original reception. As the gallery’s press release announced, the exhibition “will not fail to be of great interest to those who attentively follow fashion questions, and will no doubt inspire them.” [12] Indeed, within days of the show’s opening, the French press and beyond celebrated the fashionable and unusual exhibition and the elegance of the objects featured. An article in the weekly French journal Marianne by Surrealist poet Paul Éluard was punctuated with floating images of several disembodied headdresses, evoking the installation of similarly unmoored objects. [13] Éluard concluded his fanciful text with the claim that, “The exposition of Bushongo and Bankutu headdresses at the Charles Ratton Galleries in Paris will surely have a happy influence on fashion.”

Lilly Daché doing research in the picture collection of the New York Public Library, April 1944. Photograph by Alfred Eisenstaedt

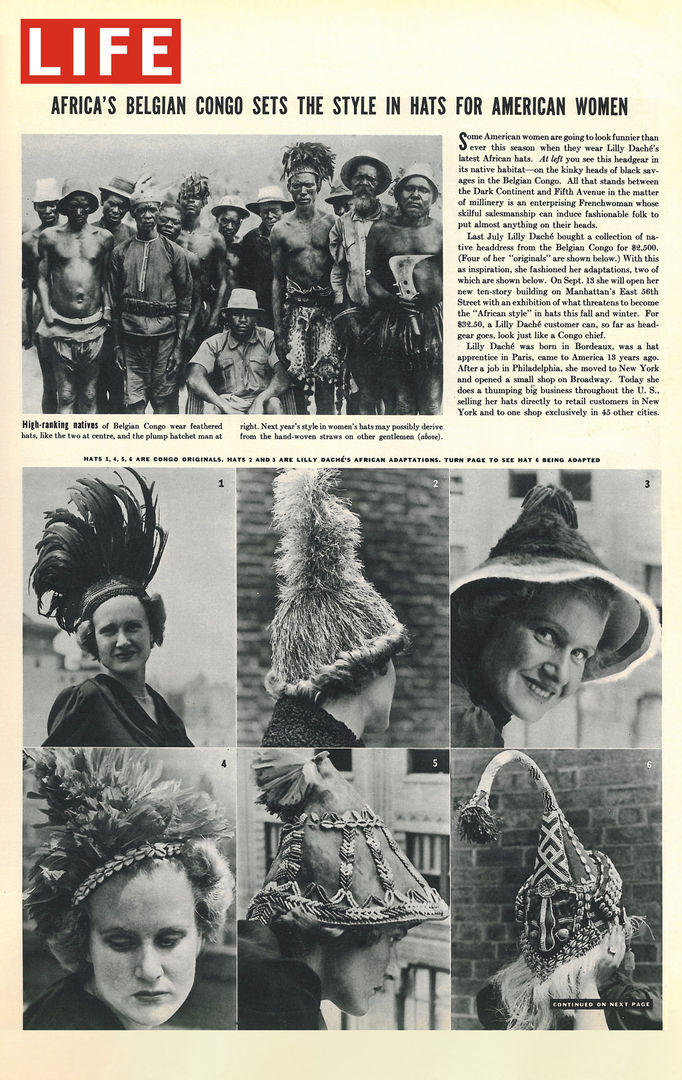

Daché responded to Éluard’s exhortation in kind. As recounted and illustrated in a Life magazine article published on September 13, 1937, she acquired the collection of headdresses two months after Ratton’s exhibition closed at the end of May, paying $2,500 for the lot. “On September 13,” the article announced, “she will open her new ten-story building on Manhattan’s East 56th Street with an exhibition of what threatens to become the ‘African style’ in hats this fall and winter.” [14] The anonymously penned Life magazine article, titled “Africa’s Belgian Congo Sets the Style in Hats for American Women,” shifts the focus from the novel headdresses to the practice of the milliner who acquired the objects for her own creative purposes. Photographs by Alfred Eisenstaedt accompany the text, featuring models wearing both the Congolese headwear and Daché’s hat designs. These seemingly interchangeable images create an equivalence between the objects and offer a compelling counterpart to Man Ray’s Mode au Congo photographs taken only months earlier.

Daché put her new acquisitions to immediate use, mounting them on the foyer wall of her tenth-floor penthouse apartment in the newly completed building. She drew upon these objects to create a body of colonial-inspired decorative forms that captured the imagination of the European and American fashion worlds. Several examples of Daché’s designs can be found today in The Costume Institute at The Met, housed in the same institution as the Congolese headwear that inspired them. From the direct appropriation of foreign goods to an assimilation of design elements and materials, Daché’s creations translated a coloniale moderne aesthetic into Western haute couture. [15]

Spread from “Africa’s Belgian Congo Sets the Style of Hats for American Women,” Life magazine, September 13, 1937.

Contemporaneous articles in French and German publications recycled Eisenstaedt’s photographs, pointing to the complicated reception of Daché’s Congolese-inspired creations and to the contingency of photographic meaning. “Where does fashion come from?” was the question posed in the title of a photo essay in the French daily paper, Ce Soir. The article answered: “A French milliner based in New York has just caused a sensation … She had the daring idea of simply taking inspiration from the hat styles worn by the natives of the Congo, and here is how she adapted them.” [16]

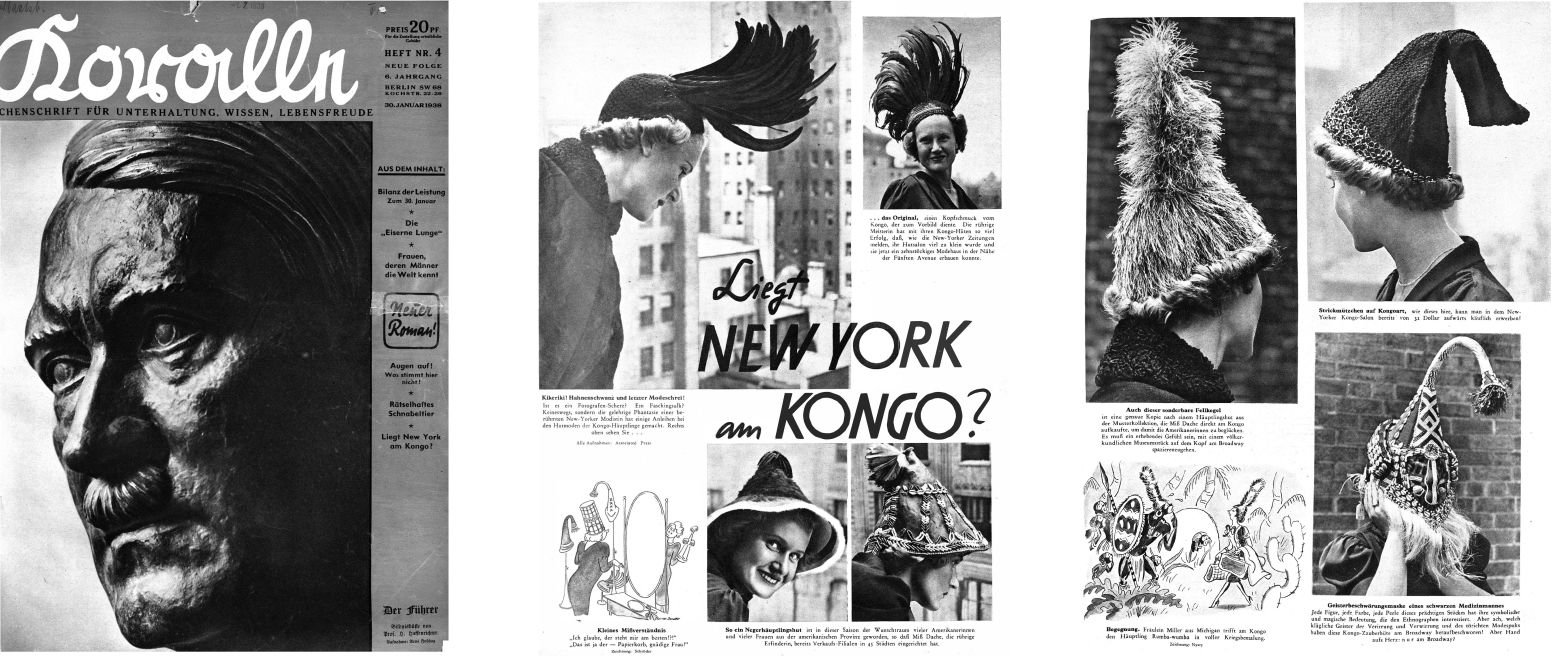

A few months later, the German weekly Koralle also found occasion to reproduce Eisenstaedt’s images. This time, however, they were employed insidiously to illustrate a derisive commentary about the new trend in headwear. [17] The article lampooned the fashion fad with the sarcastic headline “Is New York located on the Congo River?” (Liegt New York am Congo?) and sardonic captions under Eisenstaedt’s photos (“Is this a photographer’s joke?”). A stereotypical cartoon accompanying the photographs underscores the racist biases in which the editors of the publication were trafficking, echoing racial propaganda of the Third Reich.

Spread from “Is New York located on the Congo River?” (Liegt New York am Congo?), published in the German weekly Koralle, with photography by Alfred Eisenstaedt.

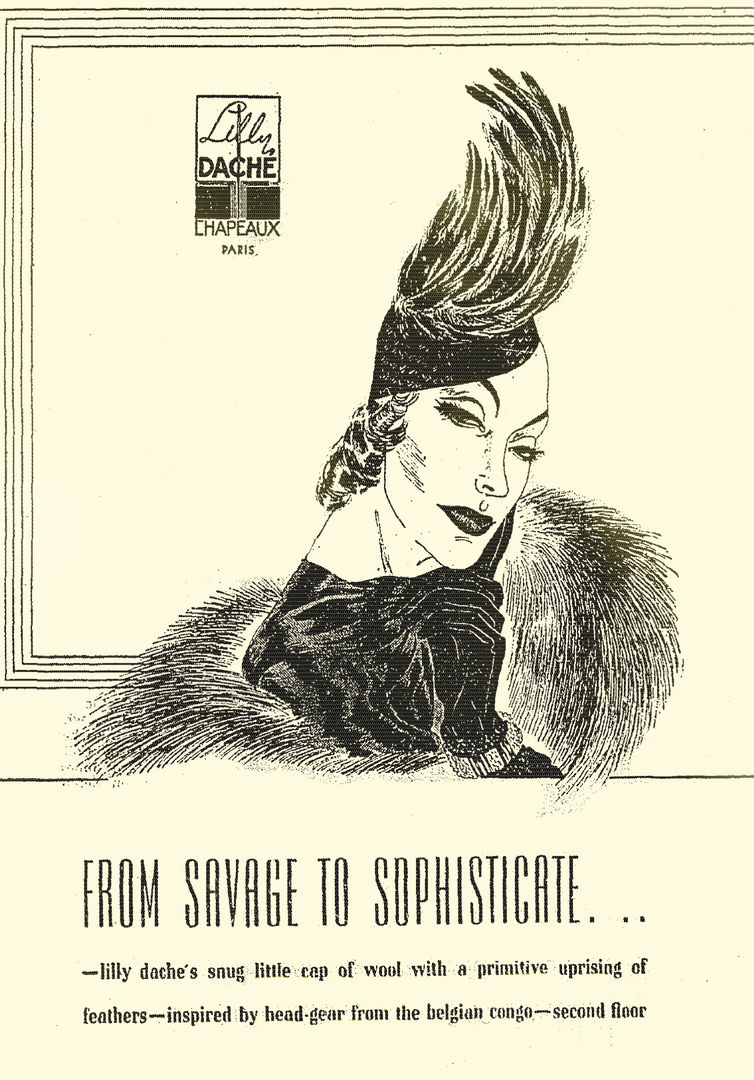

Notions of savagery and racist caricatures, as seen in the Koralle article and elsewhere in response to Daché’s new hats, reflect the complex reception of African art in all forms in the West in the colonial era. An advertisement in the Los Angeles Times featuring one of the milliner’s designs “with a primitive uprising of feathers” was promoted as transporting the wearer “From Savage to Sophisticate.” This treatment exposes insidious American attitudes about Africa that paralleled France’s so-called “civilizing mission,” the country’s pretense for pillaging the continent for its own material gains.

Bullock’s Wilshire advertisement from the Los Angeles Times, September 21, 1937

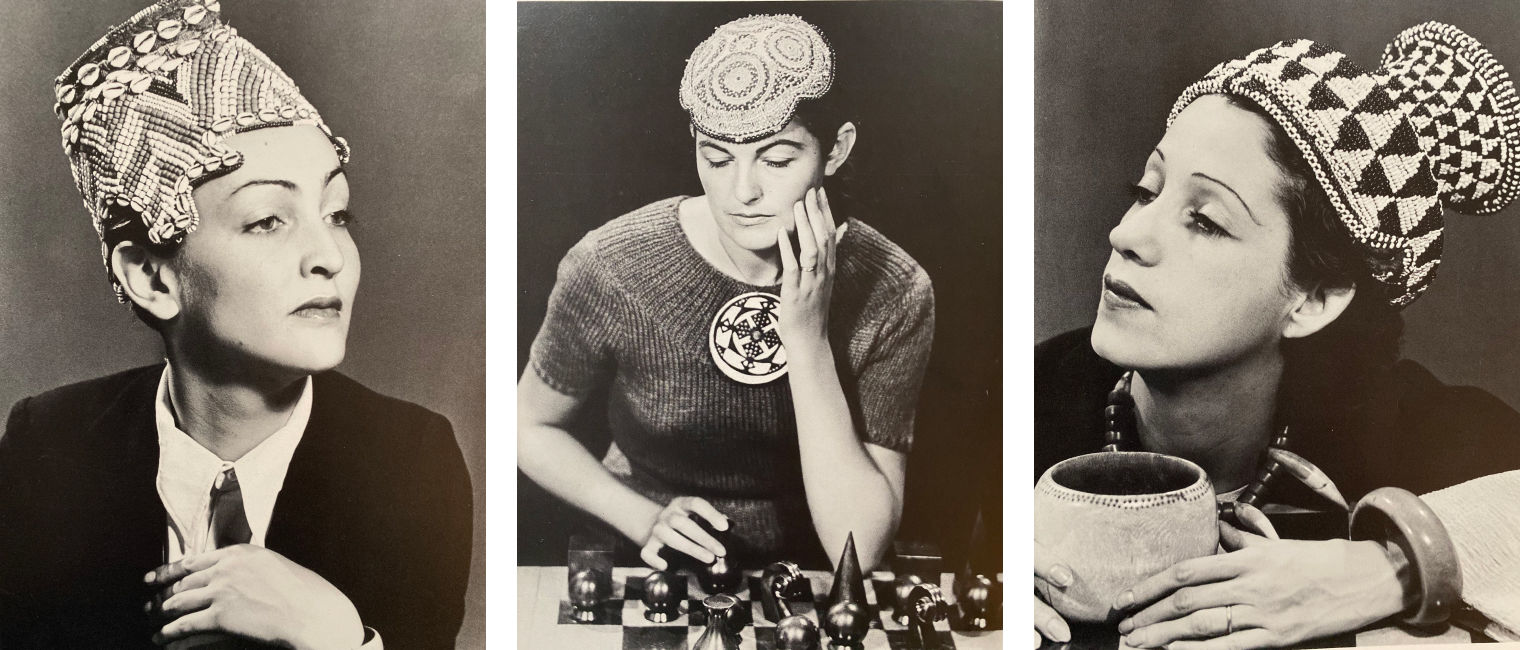

While Eisenstaedt shot his photographs in New York after the objects had been acquired by Daché, Man Ray created his Mode au Congo series when the headwear was still in Ratton’s Paris collection. Ironically, these images were published in two very different publications and contexts just days apart. The two-page spread in Harper’s Bazaar, titled “The Bushongo of Africa sends his hats to Paris,” was published on September 15, 1937, two days after the Life magazine feature on Daché. The Harper’s article was a hybrid production with an international cast of characters, conjoining Daché’s headdresses, Man Ray’s photographs, and an English translation of Éluard’s text published in the French press four months earlier. Both the poet’s fanciful prose—with its romanticized notions of the Kuba kingdom (the Bushongo), as pioneers for Parisian fashion—and Man Ray’s images assume new meanings in the context of this American publication.

Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Meret Oppenheim, Alice Rahon, and Consuelo de Saint-Exupéry from the series Mode au Congo, 1937. © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2022

Among the models Man Ray engaged in the Mode au Congo portfolio were some of the same female artists, poets, and writers who collaborated elsewhere in the artist’s inventive photographic practice. Although unidentified at the time, these include Meret Oppenheim, Alice Rahon, and Consuélo de Saint-Exupéry. The model appearing most frequently in this series, however, is Adrienne Fidelin, who had become Man Ray’s partner and muse by 1935. [18]

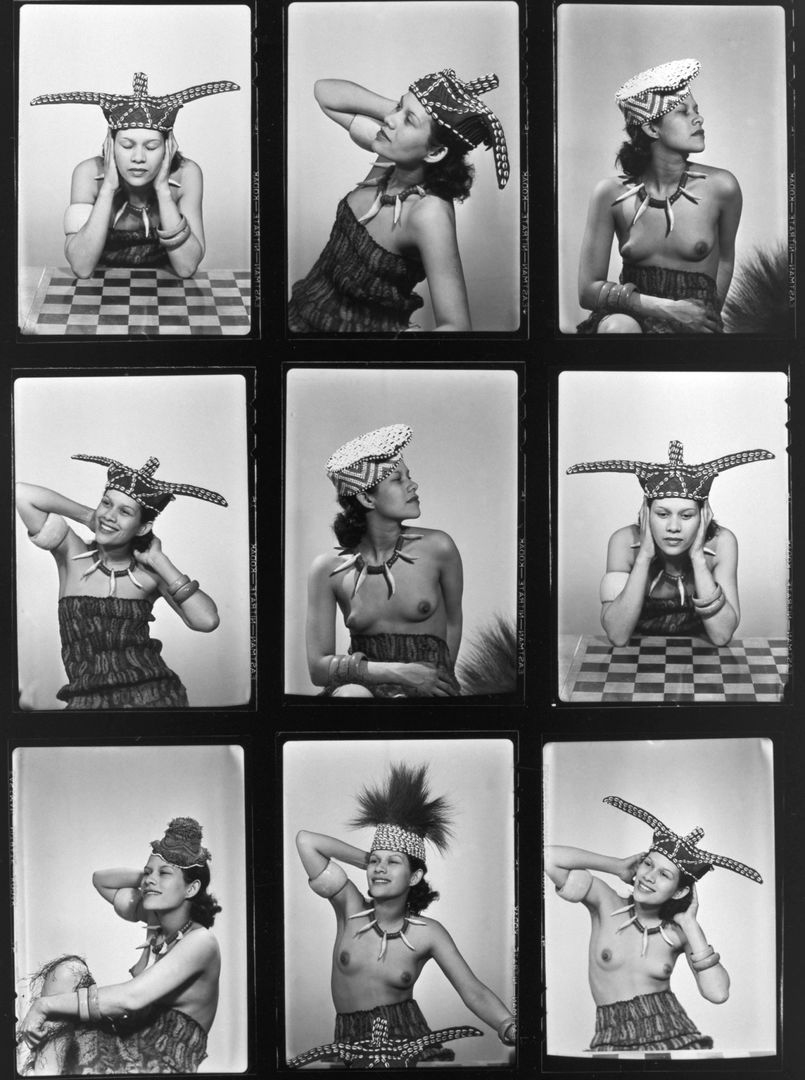

In contrast with the relatively static poses of the white models, the nine compositions featuring Ady, as Fidelin was affectionately called, reveal a far more animated and exoticized participant. Indeed, it is impossible not to notice the distinctive manner in which she is dressed, undressed, accessorized, and seductively posed. The tiger’s tooth necklace, ivory bangle, and bared breasts are cultural markers underscoring her racial otherness. Although the image from this series selected for reproduction in Harper’s Bazaar was notably cropped to hide her exposed breast (visible in the original composition), her bare shoulders intimate the naked body beyond the picture frame.

Man Ray (American 1890–1976). Adrienne Fidelin, 1937. Contact sheets for the series Mode au Congo. Gelatin silver prints. Private collection © Man Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2022

Reproduced full-page across from three smaller reproductions of other models from the Mode au Congo project, this photograph of Fidelin dominates the magazine spread. Staged to evoke the fashionable “African native” extolled in the article’s headline and Éluard’s text, she is literally and figuratively set apart from the similarly crowned white models on the opposite page. Given Fidelin’s ambiguous Creole ethnicity, however, it is the subject matter of the article and the racialized manner in which she is presented that effectively reduces her to a homogenized notion of Blackness and a projection of difference.

Yet—despite intransigent racial barriers in the fashion industry—the presentation of a light-skinned Caribbean woman under this fabricated Congolese guise unwittingly led Fidelin to become the first Black model to be featured in the pages of a major American fashion magazine. The prestige cap she sports in the Harper’s Bazaar image, which once signaled the status of a proud male initiate into a particular Kuba society, is transformed here in characteristic Surrealist fashion into a prize-winning crown. (It is notable that Fidelin’s fleeting fame, as it were, was facilitated in this manner.) Hats have an illustrious place in the history of Surrealism, appropriated for their symbolic, metaphoric, and fetishistic qualities by a number of the movement’s protagonists. [19] Situated at the intersection of fashion, Surrealism, and the craze for African art, Man Ray’s Mode au Congo photographs succinctly capture the zeitgeist of the interwar avant-garde in France. And Fidelin’s prominence in this series suggests a more significant presence within this elite circle than she has historically been accorded. [20]

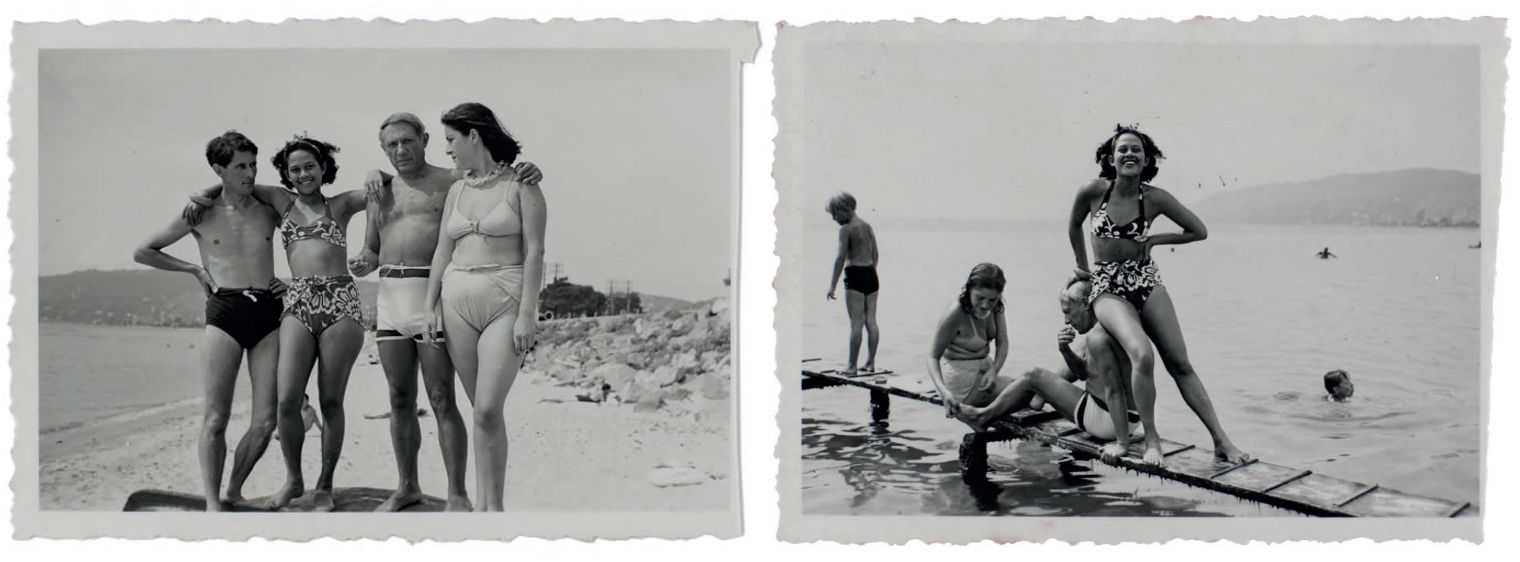

Left: Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Roland Penrose, Adrienne Fidelin, Pablo Picasso, Dora Maar, 1937. Gelatin silver print, 2 1/2 x 3 1/2 in. (6.2 x 8.5 cm). Centre Georges Pompidou, MNAM-CCI AM 1994-394 (4424). © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, Paris 2022 Right: Man Ray. Adrienne Fidelin, Pablo Picasso, Dora Maar, 1937. Gelatin silver print, 2 1/2 x 3 1/2 in. (6.1 x 8.7 cm). Centre Georges Pompidou, MNAM-CCI AM 1994-394 (4428). © May Ray 2015 Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2022

In April 2022, almost twenty years after Fidelin passed away in obscurity in the South of France, she appeared in the New York Times’ series of obituaries of previously overlooked individuals. There, she is again showcased in the same photograph from Man Ray’s Mode au Congo series. However, she is no longer an anonymous figure illustrating a fantasy narrative, but rather the subject of her own story. And the Congolese headdress she is wearing—now housed at The Met—has itself taken on new life as an object in its own right in the Museum’s collection.

In 2013, the Daché collection of Congolese headdresses originally assigned to The Met’s Costume Institute was officially transferred to the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas (now the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing), where individual pieces had occasionally been on display. Works entering the Museum under the rubric of fashion were thus unceremoniously reclassified as African art, reassigned to prioritize their geographic and cultural origins over their sartorial function. The collection underwent a transition like the one it experienced when Daché acquired it from Ratton, only in reverse.

The author presents her research as Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Director’s Office (2021–22).

Unraveling the journey of these objects and their reception provides an illuminating example of the global networks of influence and inspiration that have come to define modern fashion today and the important role of African material culture in that process. Mapping the travails of these “traveling hats” provides a unique opportunity not only to advance scholarship on the Congolese headdresses but also to take into consideration issues of appropriation at the heart of the West’s historical relationship to African cultures during the colonial modern era. How perceptions of race played out within this context is embodied in the long-marginalized story of Adrienne Fidelin. Many questions remain, foremost of which is how to expand our knowledge of the function and meanings of these hats, caps, and crowns in their original context. The history excavated here begs for further investigation into the colonial practices through which these objects entered Western collections and the implications of that history on the modernist practices that the objects inspired.

This article was updated in December 2022 to include additional research on the provenance of the Daché bequest.

Notes

[1] On Daché, see Lilly Daché, Talking Through My Hats (London: John Gifford, Ltd., 1946). Although Daché does not mention her collection of Congolese headwear, her autobiography provides extensive details about her life in the hat fashion business. See also Margaret Chase Harriman, “Hats Will Be Worn,” The New Yorker (4 April 1942): 20–27; Lilly Daché: Glamour at the Drop of a Hat (New York: Fashion Institute of Technology, 2007). “Hats off to Milliner in Hollywood’s Golden Era,” Palm Beach Post (February 7, 1990): 36. Return

[2] See Daniel Biebuyck and Nelly van den Abbeele, The Power of Headdresses: A Cross-cultural Study of Forms and Functions (Brussels: Tendi, S.A., 1984); Mary Jo Arnoldi and Christine Mullen Kreamer, ed. Crowning Achievements: African Arts of Dressing the Head (Los Angeles: University of California, Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995); Duncan Clarke, African Hats and Jewellry [sic] (Rochester, Kent, U.K., Grange Books, 1998); Christine Vanderhaeghe, “Head Ornaments of the Congo Basin,” in Parures de tête / Hairstyles and Headdresses, ed. Christiane Falgayrettes-Leveau (Paris: Musée Dapper, 2004), 205–242. Return

[3] King Leopold II’s reign over the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908 was notorious for its ruthless practices of systemic torture, murder, and amputations. International outcry led to the territory’s transfer to the Belgian parliament in 1908. The region gained its independence in 1960, adopting its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 1964. See Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999). Return

[4] Invoice from Raoul Blondiau to Ratton dated February 1, 1937. Ratton Archives, Paris. Correspondence between Ratton and Joseph Maes, curator at the Tervuren Museum, suggests that the Paris dealer traveled to Brussels in late 1936 to visit an exposition of objects from the Belgian Congo. The lot sold for 1,350 Belgian francs (980 French francs) and included hats comprised of basketwork, beads, and shells, accompanied by a photograph in which many of the objects are clearly identifiable. Return

[5] See Michelle Tolini Finamore, “Fashioning the Colonial at the Paris Expositions, 1925 and 1931,” Fashion Theory 7:3-4 (2003): 355. DOI: 10.2752/136270403778051. Accessed January 15, 2022. Return

[6] See Petrine Archer-Shaw, Negrophilia: Avant-Garde Paris and Black Culture in the 1920s (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000). Return

[7] On Ratton, see Sophie Laporte, ed. Charles Ratton : L’invention des arts « primitifs » (Paris : Musée du Quai Branly: Skira Flammarion, 2013). Although Ratton was listed as a lender to the 1931 Colonial Exposition, it is unclear if he lent to or purchased any of these headdresses from that event. Return

[8] An undated inventory in the Archives Charles Ratton – Guy Ladrière, Paris lists fifty-two “coiffures du Congo belge,” which took Ratton many years to assemble. See also Jean Frezouls, “La Mode au Congo,” La Semaine a Paris (30 April 1937): 46. I would like to thank Sandrine Ladrière for facilitating my research at the archives in December 2021 while working on this material as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at The Met. Return

[9] On Ratton’s relationship with the Surrealists, see Philippe Dagen, “Ratton, Objets Sauvages,” in Laporte, ed., Charles Ratton, 119–133. Return

[10] See Katia Sowels, “Exposition Surréaliste d’Objets, Paris,” in Surrealism Beyond Borders, ed. Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2021), 172–175; Sophie Leclercq, “As Beautiful as the Fortuitous Meeting of an Aphrodisiac Jacket and a Yup’ik Mask, or Surrealist Primitivism by Analogy,” in Surrealism and Non-Western Art: A Family Resemblance (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2014), 21-40; Didier Ottinger, “Exposition surrealiste d’objets, 1936,” in Dictionaire de l’objet surréaliste (Paris: Gallimard, 2013), 72–79; Janine Mileaf, “Body to Politics: Surrealist Exhibition of the Tribal and the Modern at the Anti-Imperialist Exhibition and the Galerie Charles Ratton,” Res 40 (2001): 239–255. Return

[11] Laurence Madeline, “The Crisis of the Object / Objects of Crisis: Exposition surréaliste d’objets at the Charles Ratton Gallery, 1936,” in Surreal Objects: Three-Dimensional Works from Dalí to Man Ray, ed. Ingrid Pfeiffer and Max Hollein, 165–173 (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2011), 172. Return

[12] Galerie Charles Ratton Press release, February 19, 1937. Charles Ratton Archives, Paris. Return

[13] Paul Éluard, “Exposition,” Marianne (May 5, 1937). Return

[14]“Africa’s Belgian Congo Sets the Style in Hats for American Women,” Life magazine (September 13, 1937): 53–54. Return

[15] See Michelle Tolini Finamore, “Fashioning the Colonial at the Paris Expositions, 1925 and 1931,” Fashion Theory 7:3-4 (2003), 345–360, DOI: 10.2752/136270403778051943. See also Morton, P. A. Hybrid Modernities: Architecture and Representation at the 1931 Colonial Exposition, Paris, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000. Return

[16] “Une modiste française installée à New York vient de faire sensation par les nouveaux modèles de chapeaux qu’elle a lancés. Elle a eu l’audacieuse idée de s’inspirer tout simplement des coiffures que portent les indigenènes du Congo, et voici comment elle les a adaptées. “D’ou vient la mode…”, Ce Soir (November 5, 1937). Return

[17] “Liegt New York am Congo,” Koralle 4 (January 30, 1938): 132–133. Return

[18] See Wendy A. Grossman and Sala E. Patterson, “Adrienne Fidelin” in Le Modèle Noir (Paris: Orsay, 2019), 306–311. Return

[19] See Richard Martin, Fashion and Surrealism (Rizzoli, 1987); Ghislaine Wood, The Surreal Body: Fetish and Fashion (London: V&A Publications, 2007); Dilys E. Blum, “Fashion and Surrealism.” In Surreal Things: Surrealism and Design, ed. Ghislaine Wood (London: V&A Publications, 2007), 139–159; Victoria Pass, “Strange glamour: fashion and surrealism in the years between the World Wars.” PhD Dissertation, University of Rochester, 2011. Return

[20] See Wendy A. Grossman, “Unmasking Adrienne Fidelin: Picasso, Man Ray, and the (In)Visibility of Racial Difference,” Modernism/modernity Spring 2020: https://doi.org/10.26597/mod.0142. Return

Source link : https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/articles/2022/9/mode-au-congo

Author :

Publish date : 2022-09-26 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.