Summary

A humanitarian crisis has gripped the people of Chad’s Lac province since conflict spilled over from neighboring Nigeria in 2014. Years on, that crisis is far from abating. Those uprooted by attacks from armed groups like Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa struggle to get basic necessities. Although Chad’s security forces have maintained control of the country’s territory, the government has largely failed to provide for its internally displaced citizens. At the same time, international attention and donor contributions to the humanitarian response have dwindled. But now, political developments in Chad have refocused international attention on the country, and a new leadership in Chad has pledged to meet the needs of internally displaced people (IDPs). Together, these events have created an opportunity for regional and international actors to pressure the government to reverse the complacency of the past.

The need for renewed engagement is clear. The number of internally displaced people in Chad has quadrupled since 2018. At the time of writing, 381,289 people are internally displaced—the vast majority of which are in the Lac province, where food insecurity and the lack of shelter are particularly dire. Some are displaced for the first time, but the majority has been forced to flee multiple times. Across the country, an estimated 6.1 million people are in need of relief assistance. Despite these trends, donors have only contributed 37 percent of the funds needed for UN agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to address these needs.

Long-term displacement brings its own challenges. Most internally displaced communities have no intention of returning to their place of origin and prefer to remain in the IDP sites where they have lived in for years. For these people, tailored responses that promote sustainability and self-sufficiency are long-overdue but require donor support. Relief groups should explore programming options that transition away from emergency assistance where possible. These include building community gardens instead of food distributions and turning certain IDP sites into legally recognized villages.

An opportunity to push donors to better respond to Chad’s humanitarian and displacement challenges may be emerging. For the first time in years, the world’s eyes are on Chad again. In April 2021, President Idriss Deby Itno’s 30-year rule ended suddenly when he was killed on the frontlines of battle with rebel groups. Within days, his son Mahamat Deby became President of the Military Transition Council. Initially Deby’s military junta was only due to stay in power for 18 months, after which democratic elections would be held. On October 1, however, Chad announced the transitional government would remain in place for an additional two years and that elections would take place after this “new phase of the transition”. While transitioning to democratic rule is crucial, the international community must not solely focus on the country’s political dynamics. Chad’s humanitarian crisis must also be addressed.

One way to do this is by holding Chad to its regional and domestic commitments on internal displacement. Despite the political uncertainty, Chadian authorities have made finally progress in operationalizing the African Union’s Kampala Convention for the protection and assistance of IDPs. Chad signed and ratified the convention, in 2010 and 2011 respectively, but it failed to follow through once it came into force in late 2012. Over the summer, a draft law “Providing protection and assistance to internally displaced persons in the Republic of Chad,” codified the measures and responsibilities laid out by the Convention. The Chadian authorities now need to adopt and implement the draft law. Before doing so, the draft law must be amended to extend its current protection for those displaced by natural disasters to those also displaced by the slow-onset effects of climate change—a crucial differentiation given Chad’s vulnerability to climate change. Chadian leadership should view amending and adopting the law as an opportunity to fulfill its responsibilities and to signal to the region and the international community that it is committed to protecting and supporting its displaced citizens.

The coming months present a unique opportunity to change how Chadian authorities and international actors work to address the country’s humanitarian and displacement crisis. It is also an opportunity to begin to build a path out of the protracted crisis for the country’s internally displaced communities.

Recommendations

The government of Chad must:

Amend the draft law on “Providing protection and assistance to internally displaced persons in the Republic of Chad” to extend protections to those displaced by slow-onset climate change. The current iteration of the draft law only protects populations displaced by natural disasters, but this should be expanded given Chad’s vulnerability to slow-onset climate change.

Work with the Parliament and National Assembly to swiftly pass the amended draft law on “Providing protection and assistance to internally displaced persons in the Republic of Chad.” Doing so is an important step in following through on its commitment to adopt and adhere to the African Union’s Kampala Convention.

Once the IDP law is adopted, set out a clear implementation plan that identifies responsible public sector institutions for each milestone. Such a plan would help guide the implementation process and should be paralleled by efforts to train Chadian authorities, at every level, on their responsibilities under the Kampala Convention.

Contribute more to salaries for teachers, nurses, and doctors. At present, most of the salaries of basic service providers such as these in the Lac province are paid for by international donors and humanitarian groups. Transitioning to more government funding would help both displaced populations and the communities that host IDPs access these crucial services.

Decrease the constant turnover of qualified government staff in positions working on the humanitarian and displacement crisis. It is crucial for staff in government institutions and ministries to be kept in positions long enough to fulfill the job requirements and to ease the process of relationship building between the government and aid organizations.

UN agencies and humanitarian organizations must:

Foster independence among displaced Chadians through sustainable long-term assistance that better links humanitarian action and development efforts. Given the protracted nature of the displacement crisis, the aid community must adapt its programming towards more sustainable and long-term interventions, including cash-based assistance and support for sustainable agricultural programming so that communities become more self-sufficient.

Create a Housing, Land, and Property working group to work with Chadian authorities to examine the feasibility of a pilot project to turn certain IDP sites into legally recognized villages. Given that displaced communities have no interest in returning to their areas of origin, it is important to explore the possibility of turning IDP sites that have been in existence for many years into formally recognized villages.

Donors must:

Address mounting humanitarian needs. After years of dwindling funding, donors must recommit to the humanitarian response in Chad—especially by supporting the food security and shelter sectors.

Use diplomatic levers to pressure the government of Chad to adopt the law on IDPs and adhere to the Kampala Convention.

Increase their in-country presence or frequency of visits to Chad. Donors need to spend more time on the ground in Chad and out of the capital in conflict zones to better understand the extent of the country’s humanitarian crisis and ways to meaningfully engage.

Research Overview

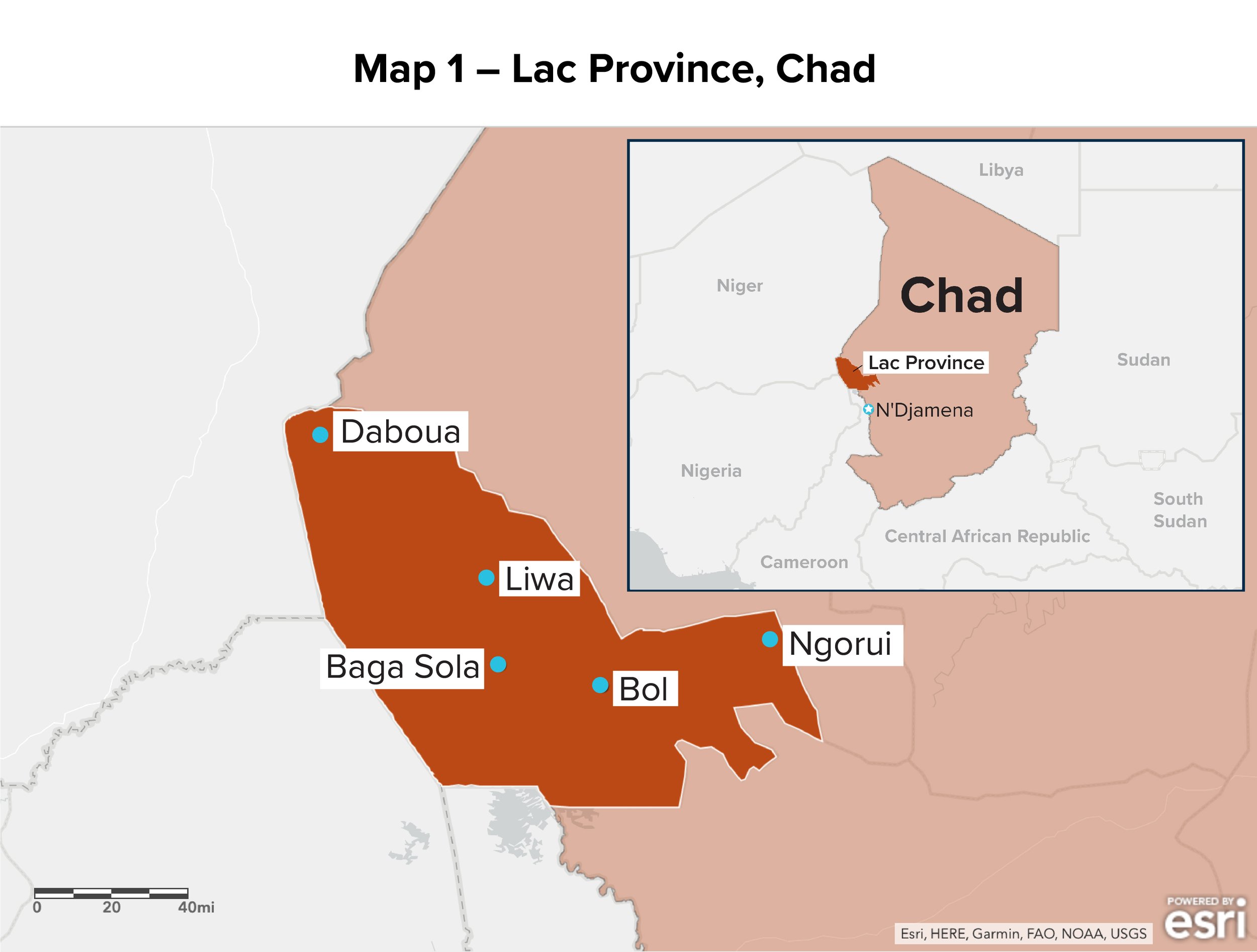

Refugees International traveled to Chad from July to August 2022 to assess ongoing efforts to operationalize the African Union’s Kampala Convention for the protection and assistance of IDPs and the effectiveness of the international response to the ongoing humanitarian crisis. The Refugees International team conducted interviews with internally displaced Chadians in the Lac province, representatives of UN agencies, donor governments, and local and international non-governmental organizations working on providing humanitarian assistance and implementing development programs.

Background

Across Chad, armed conflict, insecurity, and the crippling effects of climate change have displaced hundreds of thousands of people and left millions of people in need of humanitarian assistance.

In 2009, Boko Haram, an Islamist extremist group, launched an armed campaign in northeastern Nigeria and became one of the largest Islamist groups in Africa. The insecurity has since spread to neighboring countries along the shores of the Lake Chad Basin: Chad, Niger, and Cameroon. Since 2014, Chad has been subject to repeated attacks by armed groups—initially at the hands of Boko Haram. Over the years, Boko Haram has splintered and weakened, but other groups have joined the conflict including the Islamic State in West Africa (a Boko Haram faction). Violence associated with the conflict continue to displace the people of Chad’s Lac province and beyond.

In the Lac province, the number of internally displaced people (IDPs) have quadrupled since 2018 (see graph 1). As of September 2022, out of Chad’s 17.1 million people, 6.1 million require aid, and 381,289 are internally displaced. Additionally, the country hosts 578,842 refugees from neighboring countries. Unfortunately, the humanitarian response has not been adequately resourced. At present, aid agencies have only received 37 percent of the $510 million called for in the 2022 humanitarian appeal. As a result, aid groups are struggling to keep up with the deepening crisis.

The data was pulled on September 28, 2022. Source: OCHA: 2014–2021 and UNHCR: 2022

While some people are being displaced for the first time, the vast majority of IDPs have been displaced repeatedly. Several communities were displaced years ago and have remained in the same IDP sites. Staff from a UN agency explained that displacement for many has been pendular. IDPS, most often the men, attempt to return home in the hopes of protecting their land or working in their fields. But insecurity in their areas of origin quickly force them to flee back to the IDP site they had just left. Only a small portion of displaced people have been able to return to their areas of origin and remain there.

Humanitarian and development actors alike with whom Refugees International spoke lamented the failure of the government to allocate funding to meet the needs of its displaced citizens or to invest in development efforts. Instead, many aid workers explained, the country spends a disproportionate percentage of its budget on security expenditures. Chad is one of the world’s poorest countries and stands at 187th out of 189 countries and territories in the Human Development Index. Despite this, the government’s failure to provide even the most basic services to internally displaced people marks a significant failure of governance. An aid worker told the Refugees International team that the government “seems to have more expectations of the international community to respond to the basic needs of its people than a sense of responsibility to do it themselves.”

Source: ESRI

Source: ESRI

The majority of those displaced from communities in Lac have remained inside the province. As a result, more than 450 IDP sites can be found there. Population sizes of the sites range from a small group of people to nearly 30,000 IDPs. Each site has a unique history and set of needs. There is a significant gap between the funding and other resources available to support IDP communities and those for refugee camps in the Lac province. The latter have more permanent housing and better access to basic services such as healthcare and education. As an aid worker told the Refugees International team “the gaps are glaring, but there’s no money to respond.” This disparity is especially problematic with IDP sites that are right next to refugee camps, which have received more investment over the years.

Moreover, the country is suffering the devastating effects of climate change. Over the last few years, high temperatures and poor or torrential rainfalls have limited agriculture and decreased yearly harvests. This summer alone, erratic rainfall has impacted 340,000 people across the country—destroying property, interrupting economic activity, and displacing thousands. In June 2022, the government of Chad was forced to declare a state of emergency as the country faced mounting and widespread food insecurity and malnutrition.

These crises are unfolding in the midst of political turmoil. In April 2021, President Idriss Deby Itno was killed in a battle with rebel groups, ending his 30-year rule of the country. Shortly thereafter, his son, Mahamat Deby, declared himself leader of the country and announced that he would oversee a transitional government for 18 months until democratic elections were held. A promise which failed to come to fruition as Deby announced the decision extend the transitional government and postpone elections for another two years. This could further destabilize the country.

The Military Transition Council must, of course, follow through on its promises and prioritize holding free and fair elections. It should, however, be acknowledged for improving the government’s engagement on the question of internal displacement over the last few months. Along with international organizations, the government has endeavored to fulfill its obligations under the African Union’s Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (often called the Kampala Convention), which Chad has ratified but not incorporated into its legislation. Despite the political uncertainty, there is an opportunity to advance the protection of IDPs.

Donor Engagement

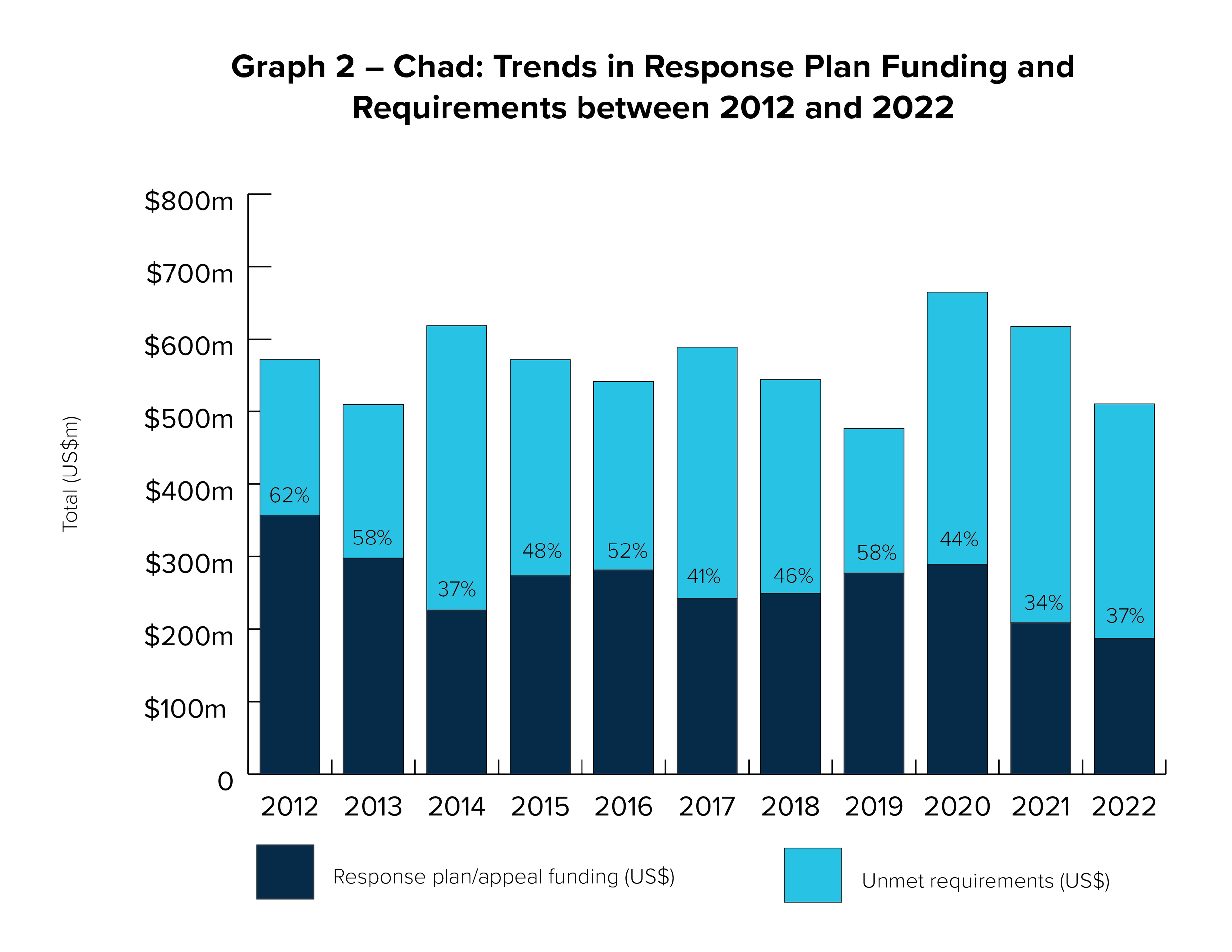

Although Chad continues to host more than half a million refugees, and the country’s humanitarian and displacement crises persist, global attention has waned over the years. In turn, so has international humanitarian donor engagement (see Graph 2). International donors, like the European Union, France, the United States, and United Kingdom provide the Chadian military with a great deal of support—both material and financial. Humanitarian funds pale in comparison. By turning a blind eye, foreign aid donors disregard the needs of displaced Chadians and overlook the fact that the crisis has continued to worsen in recent years. Indeed, 2021 witnessed the highest number of IDPs in the history of the crisis as 392,000 Chadians fled their homes. Although 11,000 IDPs returned to their areas of origin since then, the majority of remaining IDPs are unable to and are living in situations of dire need of assistance. Yet, year after year, humanitarian funds have steadily decreased.

The data was pulled on September 28, 2022. Source: OCHA

The data was pulled on September 28, 2022. Source: OCHA

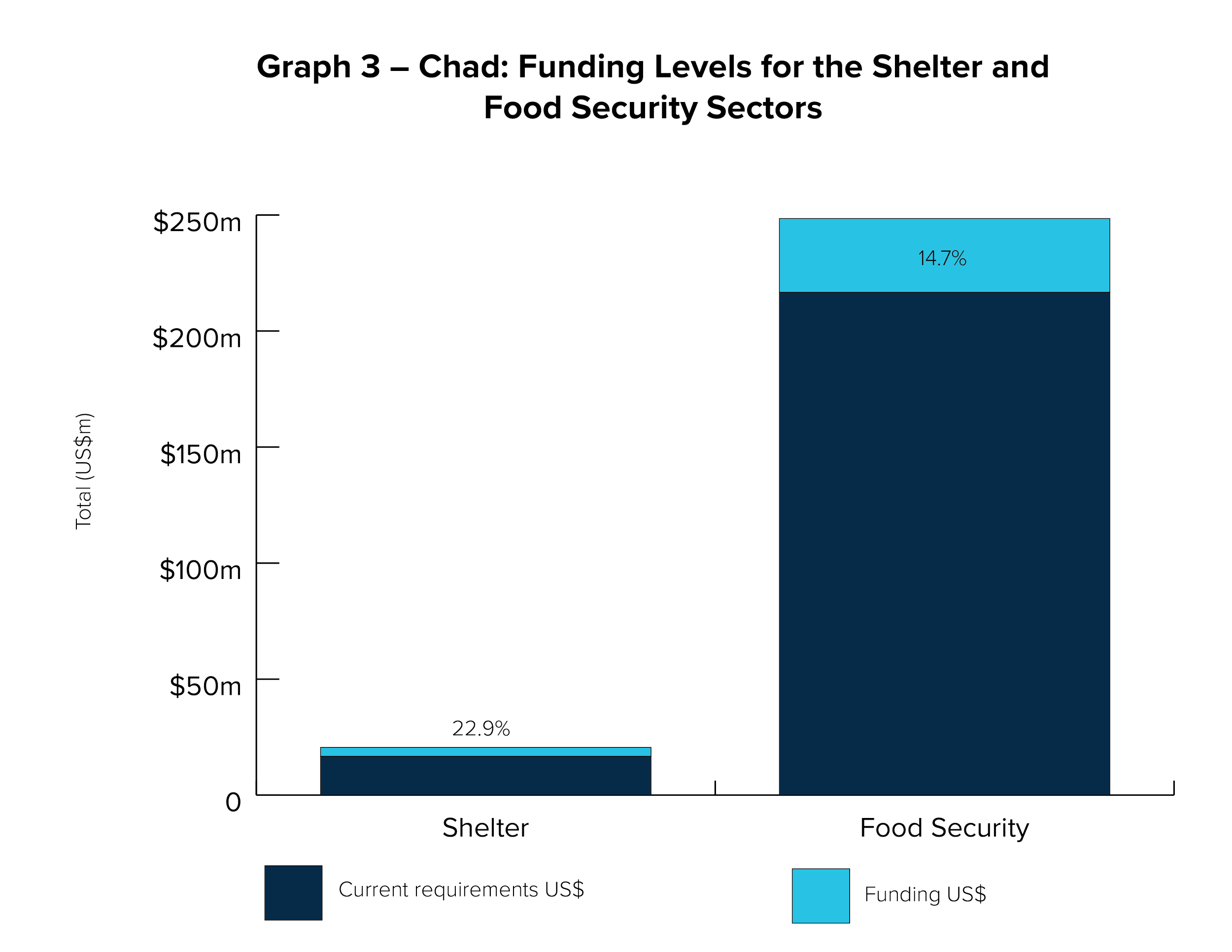

Most interviewees—whether displaced people or aid workers—mentioned that shelter and food security are the most pressing needs. However, as of mid-September 2022, these two sectors of the response had received less than 23 percent of the necessary funds for them to support people in need for 2022 (see Graph 3). Donors must re-engage in addressing Chad’s internal displacement crisis, especially in these two key sectors.

Source: Data pulled from OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service as of September 23, 2022.

Source: Data pulled from OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service as of September 23, 2022.

Despite the significant gaps in funding, NGOs and UN agencies that are operational in the region are working hard to provide a meaningful response. While Chad is home to 6.1 million people in need of assistance, the 2022 humanitarian response plan is only designed to provide for 3.9 million. This is because the aid community in country is considering the unlikelihood of getting funding to provide support for all in need and because the infrastructure in the country is not robust enough. Aid efforts usually focus on the most vulnerable first, but aid workers told Refugees International that there is not even enough assistance for those among the 3.9 million people in the country who are experiencing the most significant and pressing needs. As a result, some families experiencing crisis conditions do not receive aid while their neighbors or counterparts in other communities do. This makes it incredibly difficult for people to understand who receives aid and who does not. This in turn can increase social tension in and between communities.

Nearly every aid worker interviewed by the Refugees International team agreed that relief efforts are being well-coordinated by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Many interviewees explained that the OCHA team had shrunk significantly over the year but stressed that they were impressed by OCHA’s leadership and coordination efforts despite being understaffed and under-resourced. While these UN humanitarian staff are to be applauded for their efforts, this underscores the need for funding at every level of the response.

Humanitarian staff observed that very few international donors have a presence in Chad. Those diplomats that are present tend to be focused on the political and security situation but not the humanitarian crisis. Restrictions imposed by COVID-19 has further limited travel to communities in crisis. As a result, aid groups expressed that some donors appear to have little awareness and understanding of the true severity of the situation for internally displaced Chadians. Donor countries should work to increase their presence and frequency of visits to affected regions in the country for a better understanding of the extent of the country’s humanitarian crisis. Donor fatigue is common in most multi-year crises, and in Chad it is leaving aid groups are unable to keep up with mounting needs.

Addressing Repeated Displacement

The insecurity in some parts of the Lac province is forcing displaced people to flee the IDP sites where they first settled. When such secondary or tertiary displacement occurs, the total number of IDPs in the country does not change but needs increase. Yet aid agencies find it hard to raise international funds, as donors are drawn to crises where the total number of displaced people continues to climb. According to a UN staffer with whom the Refugees International team spoke, “most of the Lac province’s population is already displaced, and with the violence showing no signs of stopping, we can expect the same people to continue to suffer over and over.”

The country’s Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM)—co-led by Action contre la faim, ACTED, INTERSOS, UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the UN’s World Food Program (WFP) in conjunction with the government of Chad—has proved to be an effective tool for assisting newly displaced Chadians. Aid actors explained that the RRM can only be triggered when more than 50 households are displaced together. This leaves smaller groups of IDPs without much-needed help. Moreover, the RRM is only designed to assist people immediately after they were forced to flee. In practice, this means that RRM funding is only used for the first three months of displacement, leaving longer-term IDPs in the lurch. As a result, some IDPs move to new places in the hopes of receiving food assistance and access to basic services.

Insufficient funding also fuels additional waves of displacement. When IDPs cannot access aid or income-generating activities, they often continue to move in the hopes of finding safety and basic services elsewhere. The country director of an international NGO said that more funding could help people settle in safe areas instead of being repeatedly displaced. This is particularly true when that funding can unlock support for communities beyond the initial three-month period.

Transitioning Away from Emergency Assistance

Certain parts of the Lac province have become relatively more stable in recent years. Unfortunately, aid agencies have reduced services for IDP sites within these areas. During the Refugees International team’s research trip, people living in IDP sites around the town of Baga Sola (in the province’s Department of Kaya) reported feeling relatively safe but forgotten by the aid community. At one IDP site, more than 1,500 families had been living there for almost five years. They explained that the humanitarian assistance they received initially was comprehensive, but that support dwindled over the years.

Photo Caption: Self-made latrine in IDP site, which poses significant health and sanitation concerns. Photo Credit: Alexandra Lamarche, Refugees International.

Photo Caption: Self-made latrine in IDP site, which poses significant health and sanitation concerns. Photo Credit: Alexandra Lamarche, Refugees International.

In many sites around Baga Sola, shelter assistance was distributed when people initially arrived years ago, but a lack of funding has prohibited organizations from updating the shelters over time as needed to meet international humanitarian standards. Many IDPs explained that the tarps they receive wear out quickly because of the harsh sun and heat, and intense rainfall during the rainy season. One aid worker lamented that because of insufficient financing, humanitarian organizations “can’t meet standards of renewing shelter materials every six months” and that in their current state many shelters pose a significant “protection risk because shelters lack privacy and are prone to flooding which is also a health risk.” This health risk is magnified by the lack of potable water and latrines in sites. These poor hygiene and sanitation conditions, coupled with flooding, increase the exposure to disease of many of the area’s internally displaced people.

Tackling Food Security

While the WFP manages to distribute food to all IDP sites in the Lac province, the amount of food rations distributed have decreased to 50 percent because of low funding. IDPs around Baga Sola said that what they receive is not enough to tide them over between distributions. They explained that income generating opportunities were almost non-existent and access to land to grow their own food was complicated. Indeed, in November 2021 the UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that only 28 percent of IDPs had access to cultivable land. But even those who have access to land often lack the necessary seeds or tools, or that seasonal weather conditions allow them to grow enough to sustain their communities.

The WFP and other food security actors operating in the Lac province should work to increasingly support longer-term programming that allows displaced communities to become more self-sufficient. IOM has been piloting such a program in an IDP site near Baga Sola with great success.

Since 2021, IOM has supported the Ngasso project, a women-led community garden in the Dar al-Amne (also called Dar al-Amni) IDP site near Baga Sola. Women cultivated and harvested local crops to not only feed their community but also to sell off extras to generate income. IOM staff told Refugees International that the project was piloted to reduce the risk of gender-based violence (GBV) for women in Dar al-Amne by contributing to household income and increasing economic independence within the vicinity of the IDP site. Between May 2021 and March 2022, 25 vulnerable households from the site participated in activities to build their capacity in agricultural techniques and create a community farm. The total budgetary allocation for the project amounted to 24,500 Australian Dollars (close to $17,000 USD), provided by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Participants were able to harvest okra, tomatoes, onions, and maize—some of which were consumed by them and their community, and the remainder was either sold during the lean season as a source of income or kept for seeds to allow them to sow again during the next planting season. Partnering with local authorities at every step, from land selection and allocation to project implementation proved to be of crucial importance in ensuring a sense of ownership and sustainability. By partnering with the National Support Agency for Rural Development (known under the French acronym ANADER) the project was able over to better address challenges, such as pests and changes in water salinity and water quality on the allocated land.

The Ngasso project was a success on many fronts. It improved food security among the beneficiaries and the displaced population in the region, while also supporting the financial empowerment of women. Furthermore, the project succeeded in reducing the risk of GBV among women, who can work in proximity to their homes rather than having to leave their families, which could expose them to numerous protection risks. The pilot program also highlights the benefits of local and national authorities engaging meaningfully in efforts to assist displaced Chadians. This approach should be replicated across the many more stable IDP sites across the Lac province.

Long-term Planning

A 2021 report from IOM found that 91 percent of IDPs surveyed in the Lac province have no intention to return to their areas of origin because they feel safe where they have reestablished themselves. Around the same time, IOM also published a map detailing the stability of 288 different localities in the Lac province (See Map 2 TO TRANSLATE). The map shows many places scored high on the stability matrix, and that there are concentrations of stable locations in the province’s Kaya and Mamdi departments.

Map 2: Stability score of surveyed IDP sites in Chad’s Lac Province between February and March 2021, IOM: Data Tracking Mechanism: INDICE DE STABILITÉ – TCHAD (Province du Lac) RÉSULTATS DU ROUND 1, novembre 2021. IOM map above translated from French to English.

Map 2: Stability score of surveyed IDP sites in Chad’s Lac Province between February and March 2021, IOM: Data Tracking Mechanism: INDICE DE STABILITÉ – TCHAD (Province du Lac) RÉSULTATS DU ROUND 1, novembre 2021. IOM map above translated from French to English.

Areas such as these could benefit from sustainable long-term support that allows these communities to transition away from emergency assistance, much like the Ngasso project. Aid groups—both UN agencies and NGOs—should foster independence among displaced Chadians through sustainable long-term assistance that allows for smoother transitions between humanitarian action, resilience support, and development efforts. Doing so will require longer-term strategies with matching funding. Aid actors with whom Refugees International spoke explained that both European Commission’s European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) have long-term agreements for certain projects and other donors should follow suit.

Photo Caption: Young girl in an IDP site outside Baga Sola, in the province’s Department of Kaya, Chad. Photo Credit: Alexandra Lamarche, Refugees International.

Photo Caption: Young girl in an IDP site outside Baga Sola, in the province’s Department of Kaya, Chad. Photo Credit: Alexandra Lamarche, Refugees International.

In recent years, the possibility of “villagization”—turning refugee and IDP camps into official villages or being absorbed into nearby villages and towns—has been considered. The concept has been specifically discussed for IDP camps in the Lac province, but very little action has been taken to move towards implementation. Reasons to support this endeavor are varied, but as many IDP sites are on government or private property, which can be reclaimed at any time, villagizing sites would remove the element of precarity. Eventually, this would allow displaced communities to no longer identify as displaced and easily access government services (when and if they become more widely available). OCHA should consider establishing a Housing, Land, and Property Working Group to work with Chadian authorities to examine the feasibility of turning IDP sites into legally recognized villages, which should be supported by donors. Launching this working group could also help identify land to be used for sustainable long-term programs like IOM’s community garden initiative discussed above.

In a country where armed incursions and military operations still occur, these types of long-term programs are not without risk. Areas can still be hit by conflict after years of stability, but numerous aid organizations stated that they believe it is time to pilot transition programs in more stable areas. Another tool to transition away from the distribution of emergency assistance and foster independence among IDPs is to provide more cash-based assistance. In places where markets are operational, the benefits of cash distributions are numerous. Unlike in-kind distributions, they allow aid recipients to choose what to buy, fostering a sense of dignity and choice based on their needs. Cash-based responses have also proven to be more cost-effective and efficient as they are less time consuming and can be transferred remotely using mobile or card systems.

In March 2022, Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (DG ECHO) announced their new policy to increase their use of cash transfers to address humanitarian needs, which they argue is “a key tool for operationalizing the humanitarian-development nexus.” Not only does DG ECHO commit to using cash transfers, but the directorate has also called on other donors to adopt similar policies based on their shared pledges to do so under the Grand Bargain commitments on cash transfers, and the Joint Donor Statement on Humanitarian Cash Transfers. Aid organizations should continue to build on this momentum. The humanitarian Cash working group in Chad should work to promote more cash-based interventions among NGOs and UN agencies.

Any real transition from emergency assistance must bring with it government investment in basic services. An aid worker explained to the Refugees International team that the Chadian government—both past and present—“unlike some of its neighbors does not deny the extent of the country’s humanitarian crisis, but it doesn’t assume much responsibility to address it.” Both aid workers and Chadian civil servants alike criticized the national government for its lack of political will in investing in anything other than the country’s security forces.

The government of Chad must contribute more to salaries for teachers, nurses, and doctors—many of whom are currently paid for by international donors and humanitarian groups—in the Lac province and beyond. Doing so would help both displaced populations and the communities that host IDPs access basic services. The government must also invest in government bodies working on issues other than security. Substantial international diplomatic pressure is needed to compel the government to take on more of the financial responsibility of providing basic services to its citizens.

Chad’s Responsibility under the Kampala Convention

All humanitarian efforts will serve as a temporary band-aid and are unlikely to be sustainable over time without more active engagement from the Chadian authorities. The government must acknowledge and assume more of its responsibilities to tackle the consequences of internal displacement in the country. Operationalizing the Kampala Convention in Chad is an important step forward.

In June 2010, the government of Chad signed the African Union’s Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (known as the Kampala Convention). The Kampala Convention—the only legally binding instrument for the protection and assistance of IDPs in the world—created a shared understanding and commitment among African Union states of the necessary legal framework for the protection and assistance of IDPs. The Convention identifies the obligations of states to prevent, respond to, and end internal displacement.

Despite signing this historic agreement in 2010 and ratifying it a year later, the Chadian authorities largely ignored the next steps: codifying it into law and adhering to its stipulations.

In April 2019, the National Commission for Reception and Reintegration of Refugees and Repatriated Persons (which operates within the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralization and is known by the acronym CNARR) was designated to lead efforts to codify the terms of the Kampala Convention into Chadian law. Shortly thereafter, the International Commission of the Red Cross (ICRC), IOM, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), and the CNARR jointly created a working group to oversee efforts to implement the Convention.

Over the course of the summer of 2022, the working group successfully crafted a draft law—“Providing protection and assistance to internally displaced persons in the Republic of Chad” and presented it to the Government of Chad for adoption. The draft law1 protects Chadians who are internally displaced by natural disasters but does not mention those displaced by the slow-onset effects of climate change. This is particularly important in Chad, which is the third most vulnerable country to climate change out of 190 countries, according to the University of Notre Dame’s GAIN Index. In an effort to address and foresee displacement trends, the government of Chad, with support from IOM, UNHCR, and ICRC, should amend the law to extend the protections of the Kampala Convention to those impacted by climate change. Following the law’s formal adoption, the working group should create an action plan that identifies key milestones for implementation and the government bodies responsible for each step.

According to those participating in the process, the draft law now sits with the country’s Prime Minister Albert Pahimi Padacké, who is charged with presenting it to the parliament. Once the members of the parliament approve the draft law, it should then go to the country’s National Assembly for the law’s final approval and adoption.

Refugees International applauds the Chadian authorities for their openness and good faith efforts in this landmark advancement, but the momentum must not be lost. The law should be edited to include all those displaced by climate change and officially adopted with a clear plan for its implementation. Diplomatic pressure must be applied on Chadian authorities to do so. This may be a particularly good opportunity as the Military Transition Council may be more receptive in the hopes of gaining international legitimacy.

At present, interactions between the humanitarian community and Chadian authorities can be complicated. Governors, préfets and sous-préfets (sub-provincial local authorities at the Department and Sous-préfecture level respectively), lack understanding of humanitarian action and in some places, have interrupted aid activities. Humanitarian actors told the Refugees International team that local authorities have taken over structures used by aid organizations in some locations. In others, they have demanded that humanitarian groups hire their family members.

The relationship between relief actors and the government is further complicated by the quick turnover of staff within Ministries, Governorates, and the CNARR. One humanitarian worker complained to the Refugees International team that the CNARR is not given the resources it needs to fulfill its mandate and “is a revolving door” when it comes to staffing. They went on to explain that while the staff of the CNARR and other government bodies are keen to engage with UN agencies and NGOs, building new relationships with government counterparts when they change every few months slows down relief efforts and cooperation.

These numerous types of interruptions and slowdowns go against the Convention and must cease. Article V (7) and (8) of the Kampala Convention says that the State must “allow rapid and unimpeded passage of all relief consignments, equipment, and personnel to internally displaced persons” and “uphold and ensure respect for the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence of humanitarian actors.” To show its commitment to the terms of the Convention, the government of Chad should ensure that qualified staff is kept in positions, within the CNARR and other government institutions, long enough to fulfill the job requirements and for Chadian authorities, at every level, to be trained on their responsibilities under the Kampala Convention.

Conclusion

The responsibility to provide protection, aid, and security for Chad’s population experiencing internal displacement and humanitarian needs lies primarily with the country’s government. Following through on its commitments under the Kampala Convention is a key step in the right direction and one that global donor countries can help to influence. The momentum to codify its terms into Chadian national law must not be lost.

While national authorities and international powers are seized with the country’s transition to civilian rule, the humanitarian crisis must not be ignored. Insufficient financial and diplomatic engagement will continue to have dangerous consequences on the civilian population.

This report was supported by the Robert Bosch Stiftung and is part of a wider research and advocacy initiative on internal displacement.

Cover Photo Caption: Group of internally displaced men in a displacement site outside of Baga Sola, in the province’s Department of Kaya, Chad. Photo Credit: Alexandra Lamarche, Refugees International.

Editor’s Note

The report was updated on October 12, 2022 to reflect significant developments in Chad since publication on September 29, 2022.

Source link : https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports-briefs/responding-to-chads-displacement-crisis-in-the-lac-province-and-the-implementation-of-the-kampala-convention/

Author :

Publish date : 2022-09-29 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.