The Central African Republic (CAR) has seen more than its fair share of conflict and a long string of agreements to try to resolve it. The country plunged into crisis in 2013, when a coalition of armed groups known as the Seleka seized the capital city of Bangui. Although 2014 saw the deployment of a UN peacekeeping mission (MINUSCA) and installation of a transitional government, the country has yet to find a stable footing. In a February 2019 political agreement between the government and fourteen armed groups – the sixth since the 2013 crisis – the government committed to integrate some groups’ fighters into the national army and their leaders into government. But implementation has been patchy, and armed groups still hold sway in much of the country. Many of CAR’s five million people fear that fighting may break out again as presidential and parliamentary elections near in December 2020.

In November 2019, I travel to CAR to try to understand the risks and opportunities for this impoverished nation as it approaches next year’s elections. My focus is not on external actors – the UN peacekeepers or regional actors who brokered the February 2019 deal –who grab the attention of global media that tend to see CAR as a perennially failed state and look to the outside world for answers to its problems. Instead, I want to delve into the country’s internal dynamics. As a researcher working on deadly conflict in Central Africa, I am convinced that if there is to be a long-term chance of internal peace, or meaningful elections, it will have to come in large part from within.

As I begin research on a report that will consider how to achieve peaceful elections and take steps toward a better future, the picture seems mixed: CAR is a country that faces enormous challenges but where small signs of progress give hope that a more peaceful future could be within reach. I decide to start with a broad survey and talk to the ruling and opposition parties, travel out to the countryside to meet with armed group leaders, check in with representatives of the faith community, and look into whether progress is being made on efforts to increase women’s political participation.

A small white sign on the hill above the main Catholic cathedral welcomes visitors to the capital. Given the dangers of most overland routes to CAR, the only safe way to reach Bangui is by air. As a national of Cameroon, I just need an airport stamp in my passport to enter the country.

One kilometer from the cathedral is the capital’s central roundabout, which is called PK0, for “point kilométrique zero”, the zero point from which all distances are measured. Here stands a statue of Barthélemy Boganda, who became CAR’s first president after it gained independence in 1960, and the national slogan of Zo kwe Zo: “The country where every human being is treated as a human being”.

As we drive into town, Bangui feels more like a big village than a city, although with a few high-rise buildings along the Ubangi River that forms the border between CAR and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

It’s quicker to arrange meetings with opposition leaders than government ministers, so I start with them.

One of my first discussions is with Alexandre N’Guendet, leader of the Rassemblement Patriotique pour la République and a former head of state.

I learn that the government has withdrawn his passport and removed his security detail. He claims that he was threatened with a gun at an opposition rally by a young man close to the government.

N’Guendet tells me that he is not against those currently in power, and has sought to work with them but has been rebuffed. He says that’s why his party quit the presidential majority in the National Assembly in 2017.

I also meet with representatives from the country’s armed groups while I am in Bangui.

There are at least fifteen armed groups in CAR, fourteen of them party to the February 2019 political agreement. Most citizens see the armed groups as predatory and accuse them of living off illegal tax schemes and abuse of the civilian population. But peace won’t be possible without taking their views into account.

Representatives from Revolutionary Justice Sayo (RJ Sayo) agree to meet me late one evening. RJ Sayo is one of the smaller armed groups and has officially volunteered to go through a process of disarmament, demobilisation, reintegration and repatriation. But its leaders complain that they are not being treated well, while other groups that have not disarmed have been granted important positions in the government and administration.

One of my visitors used to be the group’s military chief. He is sceptical that DDRR will work out. He shares a lesson he took away from his prior role: if you want to be taken seriously, you have to keep your weapons.

From my motel window, I watch a rehearsal for a Central African Security Forces parade in honour of CAR National Day on 1 December.

CAR covers nearly as much territory as France. Yet the military that must secure that territory comprises fewer than 10,000 people. Of that number, only 3,500 to 4,000 are really operational – and even they are poorly equipped.

Equipping the army is partly made more difficult by an international arms embargo on CAR that is meant to target the country’s armed groups. The UN has gradually reduced the scope of the embargo over the last year. But even if there were no embargo, it’s not clear that CAR has either the money to buy much new equipment or the capacity to put it to good use. CAR’s national budget is only $480 million, with roughly 10 per cent going to the military.

I brief U.S. Ambassador Lucy Tamlyn on my ongoing field work and note down her observations.

From my first contacts, I have already formed two impressions. One is that the February 2019 peace deal is under strain. Violence against civilians is still high, some armed groups have even enlarged the area under their control and a complete DDRR process is very unlikely to wrap up before the elections. The other is that MINUSCA and CAR security forces would likely struggle to quell violence were it to build up ahead of the December 2020 elections. Only 1,500 CAR soldiers are deployed out of the capital and, except for a Portuguese battalion, few of the 12,870 MINUSCA troops are equipped or ready for operations against the armed groups, which are estimated to field between 8,000 to 14,000 fighters.

These are the kinds of issues that I will want to bring to the attention of Crisis Group’s readers. But I’m nowhere near ready to start writing. Before I know enough to do that, I’ll likely have to talk to more than 100 people. These will include state officials, individuals involved in mediation with the armed groups, representatives of humanitarian NGOs and diplomats from regional organisations and interested foreign powers like Chad, France and the U.S.

I will listen to new information, test ideas as they come up and seek support for recommendations we have developed in our long-running work on how to end the violence in CAR.

I meet with Thierry Zeneth, the director of elections at the Ministry of Territorial Administration. He is the lead CAR official in charge of preparing the December 2020 elections. I want to discuss technical details of the upcoming polls and get a reaction to opposition claims that CAR is in no position to stage them.

His responses are clear and detailed, but they also show how far the government has to go. He argues that while there may be fighting in the countryside, the situation is better than in 2015-2016, when elections went ahead despite the violence, including in the capital. Also, he points out that donors have already pledged half of the roughly 63 million euros needed for the poll. CAR itself has put aside about 2 million euros in 2019 and promised another 2 million in 2020.

CAR’s former ruling party, Kwa Na Kwa (known by its initials KNK and meaning “Work, Only Work”), is one of the most important political forces in the country. I meet two of its leaders, Bertin Bea and Francis Bozizé, at their party’s headquarters in Bangui. They ask not to be photographed, saying that they aren’t smartly dressed.

Bea and Bozizé – who is the son of former President François Bozizé, ousted in a 2013 coup after ten years in power – are also under pressure from the government. The government confiscated Francis Bozizé’s passport and official documents, banned him from leaving Bangui and charged him with complicity in murder and torture. These charges are widely understood to be politically motivated. Still, I learn that KNK is open to an alliance in the forthcoming elections with the current president, Faustin-Archange Touadéra, who was also once the number two in the party.

Just after my trip, on 15 December, the situation becomes even more complicated. Former President François Bozizé returns clandestinely to Bangui and in January makes clear that he will engage in politics, either by standing for president or by supporting an opposition candidate. Since he remains relatively popular with a significant number of sympathisers in the military, the government seems to be hesitating to arrest him.

I meet three ministers, including Maxime Mokom (right), the minister for disarmament, demobilisation, reintegration and repatriation. He shows me a list that his secretary has printed out. It reflects progress toward DDRR of the armed groups that are participating in the process.

Mokom is the head of an armed group and a signatory to the February 2019 agreement. He seems to have only a dozen people working for him, and his office is a bit ad hoc. Other ministerial offices look more formal. He tells me of his trips to remote areas of the country to convince armed group leaders to give up their arms. He seems on top of his brief, motivated to share what he is working on and committed to his DDRR mission. His own armed group, Anti-balaka Mokom, has already started the DDRR process.

To find out more about the political dynamics of CAR, I want to gauge the attitudes of young people. I seek out a representative of the 15,000 students at the University of Bangui, the only state-run university in the country.

It turns out that campus politics mirrors national politics. I meet Josué Singa, who has just been elected president of the National Association of Central African Students, beating a candidate supported by President Touadéra.

Josué has no political affiliation but is clearly ambitious. He quotes Barack Obama or Nelson Mandela every few sentences, reels off his many academic qualifications and talks about women’s rights. He repeatedly says: “We believe in the future of our country”. I’m not sure if he’s telling me what he thinks or what he thinks I want to hear. But he has a way with words and I fully expect that he will play a role in CAR’s future political life.

I decide to go to Bria, 600km to the east of Bangui, to get a feel for what is happening in the countryside. Armed groups are strong there and clashes break out from time to time, but things are quiet now.

In my native Cameroon, I’d travel a distance of this length overland, but in CAR that would take several days and I would have to evade armed groups. With ground travel too risky, I look to air travel options.

There are hardly any. There is no national airline, or indeed any private airline operating inside the country. Even the capital is only served by a few foreign carriers. The government doesn’t have a single aircraft. So I arrange to travel on a UN-affiliated plane.

Also sharing our flight are international NGO workers on their way to provide humanitarian relief to persons displaced by the intermittent fighting. There are more than 45,000 displaced people living in shacks on the edge of Bria, a town of less than 60,000.

Bria is well-known in CAR for its diamond business. A big billboard welcomes visitors to Bria la Scintillante, or Bria the Sparkling. There are some modern cement houses that are mostly owned by people trading or mining the precious stones in nearby villages and rivers. Otherwise, the town is very poor.

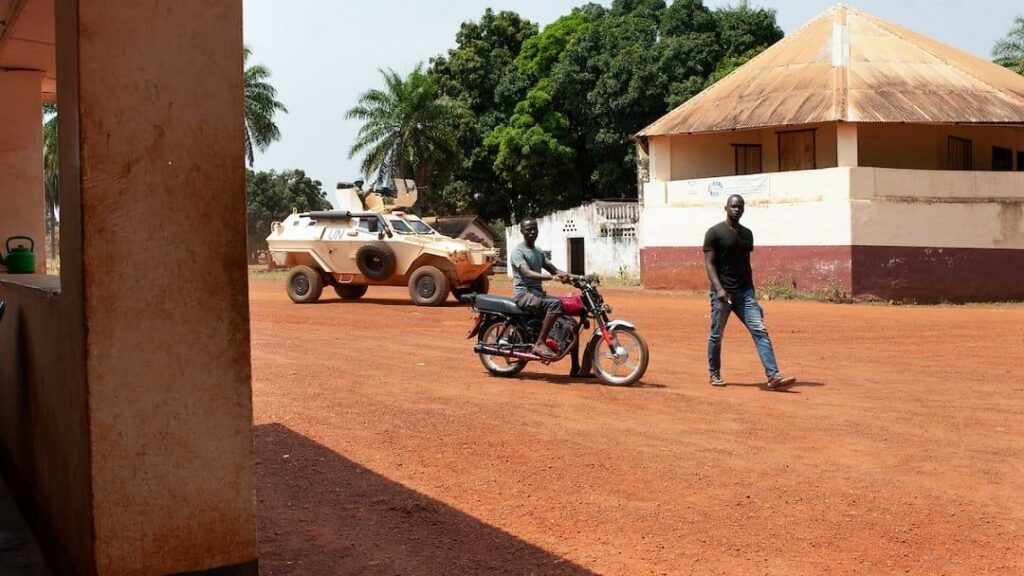

Bria is mainly controlled by five armed groups, which collectively have several hundred fighters on the street. This is not authorised by the February 2019 deal, but the state is absent or very weak in provinces. Armed groups are not the only players. There is a contingent of several hundred MINUSCA peacekeepers from Rwanda, Zambia, Sri Lanka and other countries. As in several other towns across CAR, there is also a small Russian military base, with about 40-45 soldiers, several tanks and all-terrain vehicles. A month before my arrival, 82 government soldiers and two gendarmes also came to town.

My conversations reveal that the February 2019 deal has brought some reduction of violence among this mix of armed actors. Some ex-combatants have become motorbike taxi drivers. Humanitarian aid has improved and there are fewer kidnappings. Violent conflict is never far away, however. Ten weeks after my visit, clashes among different factions in one of the armed groups – the Front populaire pour la renaissance de la Centrafrique (FPRC) – killed over 50 people, according to the Bria district prefect.

Stabilising CAR outside Bangui is an enormous challenge. There are vast areas of the country where nobody is in control. The government was proud when, recently, it could say it had redeployed 2,000 soldiers, gendarmes and policemen outside the capital. This number, however, remains insufficient for a country of 622,000 square kilometers, and the deployed soldiers rely heavily on MINUSCA for logistics.

When I come to a town facing tensions, I like to meet people involved in reconciliation processes, usually religious or community leaders. At the time of my visit, a group of local religious leaders, alongside the Bria district prefect and a Western mediation organisation, have just helped defuse a growing risk of infighting between armed groups and inter-tribal violence in Bria.

One member of the group, the Religious Platform for Dialogue, is Abbé Bruno, a Bria parish vicar. Abbé Bruno is sheltering many hundreds of displaced persons in his church. He is proud of offering help to those who need it. He has housed both Christians and Muslims here.

Abbé Bruno believes that it is important to talk to armed group leaders about the challenges facing the community. “When you speak to the armed groups’ leaders about local issues, they listen”, he says. “They take decisions”.

A Muslim woman walks on a street in Bria. This town has always been both Muslim and Christian, and the two religious communities lived peacefully side by side until 2013. Armed groups then drove the communities apart for many years.

I’m glad to see that relations between the two communities have improved. Muslims and Christians are starting to buy goods in each other’s’ markets. In my conversations I hear local leaders saying that religious polarisation has lessened in recent months.

It proves complicated navigating among the town’s administration, government representatives, armed groups and the UN. For instance, when we meet the leader of the FPRC, the main armed group in town, he asks if we have the district prefect’s permission. And when I meet the prefect, he asks if we have the FPRC’s permission. Prefects in towns like Bria have to be in constant negotiation with armed groups, recognising their local role.

During my visit to the prefect, a woman arrives with a bruised left arm and bleeding eyebrow. She is accompanied by a policeman from the UN, where she first went to complain that her husband had beaten her. The prefect asks the woman in which neighbourhood she was beaten. Knowing which armed group is in charge of that part of town, he assigns that armed group’s leader to “talk” to the husband.

Later, I ask another woman what such a “talk” means. She replies that the armed group will likely beat the husband up to “teach him a lesson” and ask for money for compensation – ostensibly for the victim – but which the armed group usually keeps.

Many members of armed groups would rather live normal lives. In an NGO compound, I meet Suleyman, a colonel in the FPRC armed group. He tells me he joined a tribal militia in his early thirties after a family member was killed by another armed group. Back then, he wanted revenge. Things are different now.

“There are too many divisions in the group because of ethnic differences”, he says. “I want to get back into the diamond business. I used to be a well-off trader”.

Heavy fighting in 2017 and 2018 did much damage to Bria. International aid has helped restore all the official buildings. But most civilian houses remain in ruins, like this one near the town centre, burned and looted in 2017.

There is no local television in Bria. Electric power and internet access are hard to find. Information tends to travel by radio. So a radio presenter like Arafonsa at the Voice of Barangbaké – the town’s only station – performs a vital role.

During the fighting in 2017 and 2018, which even wrecked the prefect’s house, nobody touched the Voice of Barangbaké. The director of the station – which is funded by the EU – says the reason they escaped destruction is because their reporting is unbiased and because the station is the only way that anybody can address the whole town at once.

In a shantytown on the outskirts of Bria live 45,000 people who have been forced from their homes by local violence over the past several years. The UN patrols the main thoroughfares by day but disappears at night. The rest of the time an armed group known as anti-balaka, a self-proclaimed self-defence group, provides rudimentary justice and protection in return for money and goods that it extorts from the displaced inhabitants.

Next to the FPRC, the second largest armed group in CAR is the Union for Peace in CAR (UPC), which is dominated by the Fulani people, who are mostly Muslim herders of livestock. Although UPC has between 2,000 and 4,000 combatants nationwide, only 100 of them are in Bria. I ask “General” Adamou Sidicki, their leader in Bria, about the future. He is very cautious. “Peace is coming back, bit by bit”, he says at his headquarters. “We are the forces of law and order here. We don’t take sides in civilian affairs”.

I leave Bria with as many new questions as answers about how the state in CAR can build its authority. New violence and disruption are possible, but I find modest grounds for optimism, too. The number of displaced people has gone down to 45,000 in 2019 and 2020 from 92,000 in 2018. Secondly, most armed groups’ combatants I talked to want to join the DDRR program, even if they complain about delays.

There are other reasons for hope as well. For instance, CAR’s National Assembly adopted a new electoral code in 2019. I’m trying to understand what is new and how it could affect the forthcoming elections. One important feature is that the law obliges all parties to present slates that have 35 per cent women.

There are lots of questions about how this will work in practice. I wonder if it will be like countries in the region where the opportunity to seek office tends to be reserved for the wives or relatives of politicians and wealthy men. I ask several women if they will need to ask their husbands’ permission to run. They tell me that a few husbands try to block their wives, a few actively support them and most don’t mind either way.

I’ve already heard an opposition party leader say women may hesitate to seek office because they lack the money needed to campaign or fear reactions in their community. The leader says another problem is high illiteracy among women (the new code specifies that all candidates must be able to read and write).

Back in Bangui, I stop by the offices of the Central African Women’s Organisation (OFCA) to discuss this reform. With more than 100,000 members, OFCA is not just the largest women’s association in the country, it is one of the largest organisations of any kind.

At OFCA, I meet Octavie, who is looking into what’s happening ahead of the elections. She says the 35 per cent women initiative was started by former interim president Catherine Samba-Panza – who took the reins of the country in the aftermath of the 2013-2014 violence – and kept up by President Touadéra, who followed her in 2016. Foreign donors like the World Bank are helping, too.

I learn that the 35 per cent quota is unlikely to be met this year. There is no penalty: parties that can’t meet the target just need to send a note of explanation to the Constitutional Court. But it will probably help increase the ratio of women in CAR’s National Assembly, currently twelve of 140, or 8.6 per cent.

Octavie assures me that women are more politically active than in the past. Already the CAR parliament includes women who are there because they wished to run, and because their constituents supported them, not because of family ties. The movement, she says, is gathering strength.

Source link : https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/central-african-republic/search-state-central-african-republic

Author :

Publish date : 2020-03-13 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.