Former Senior Analyst, Chad

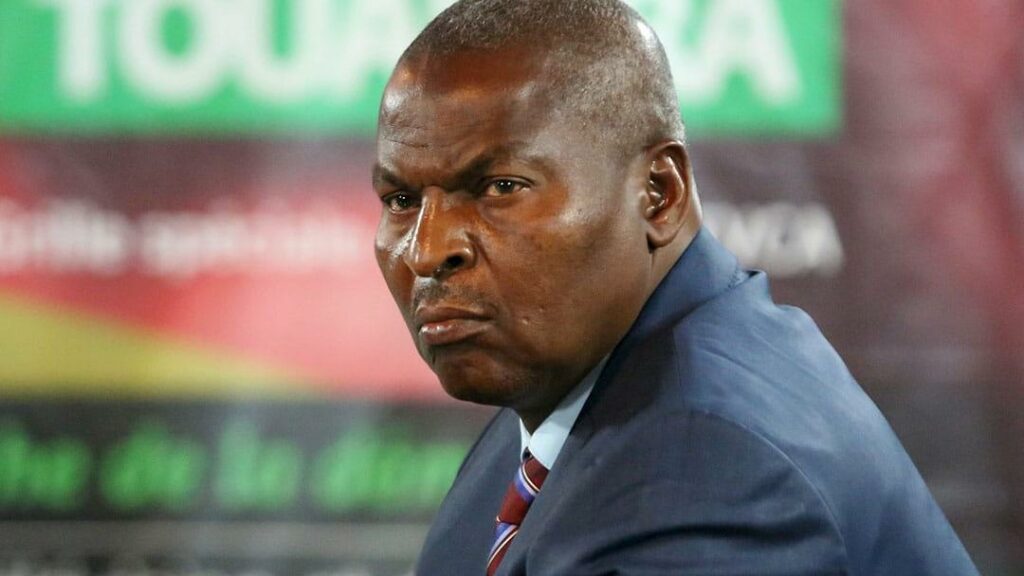

An arduous three-year political transition came to an end in the Central African Republic (CAR) on 30 March with the inauguration of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, winner in the 14 February run-off presidential elections with almost 63 per cent of the vote. But the country’s crisis is far from over.

Overall voters flocked to the polls demonstrating their strong desire to turn a new page.

The new president enjoys strong support among the population but still faces many challenges on CAR’s long road to stability. While violence has abated in some cities including the capital, Bangui, nationals and outsiders alike should not forget about the deeply engrained drivers of conflict. The crisis that erupted at the end of 2012 – the country’s worst since independence – tore apart the social fabric. With the factors that led to it still unaddressed, CAR could backslide. Politicians and rebels are still able to mobilise youth in urban areas, violent crime is a daily reality for rural communities, and armed groups, especially the ex-Seleka (coalition of armed groups from northern CAR who seized power in 2013), still control swathes of territory and could cause more trouble.

At this delicate juncture, the new president has his work cut out. He will have to break with his predecessors and put an end to political patronage, which over the last 30 years has contributed to the erosion of state institutions and the economy. He will have to fight impunity for violent and economic crimes. With the support of international partners, he will also have to revive economic activity to provide unemployed youth alternatives to violence. But as a new political chapter begins, the government and international community should focus their efforts on four critical issues: advancing reconciliation, developing a strategy to help refugees return home, fighting impunity and resolving the thorny question of what to do with the armed groups.

A New Political Chapter Presents Risks and Opportunities

The presidential and legislative elections at the end of 2015 and beginning of 2016 raised expectations across the country, as witnessed by Crisis Group in Bangui in March. Though the turnout dropped considerably in the second round legislative and presidential polls (and their chaotic organisation raised concerns for the credibility of the results), overall voters flocked to the polls demonstrating their strong desire to turn a new page. This new political chapter carries several risks, but also presents a long-awaited opportunity for CAR to strengthen its democratic institutions and practices. Parliament, which now comprises many members who stood as independents and who come from minor political parties, could transform from the ruling party’s rubber stamp into a genuinely democratic space. While Touadéra can rely on the parties that backed him in the run-off vote and some independent MPs seem to have rallied around him, he will have to win over more to secure the majority he needs to govern effectively.

Despite his popularity, from the outset Touadéra will have to deal with many grievances. He will have to distance himself from several unsavoury supporters – including allies of former President Bozizé some of whom who played a role in mobilising anti-balaka militias – while still retaining the support of those who had been loyal to Bozizé’s Kwa na Kwa party. The appointment as prime minister of Simplice Sarandji, former secretary general of the University of Bangui and former head of cabinet during Touadéra’s own time as PM, is an encouraging sign. Similarly, the composition of the new government avoided some pitfalls. Touadéra used appointments to thank several people for their support in the second round, including Jean-Serge Bokassa, now minister of the interior, public security and territorial administration, and Charles Amel Doubane, now foreign minister. He brought in several of Bozizé’s former ministers, appointing one his vice president, while excluding leaders of armed groups and their supporters – a move quickly criticised by ex-Seleka barons. The appointment of advisors will be his next big test. Though under considerable pressure, he should stick to his principles and, to avoid repeating his predecessors’ mistakes, refrain from co-opting rebels.

National Reconciliation: CAR’s “Rubik’s Cube”

The crisis revealed strong communal tensions, some of which have deep historical roots. Today, national reconciliation and social cohesion have become much-repeated slogans. Even some armed groups have expressed a desire to be involved, albeit with some cynicism. Reconciliation, however, will take a long time. Questions of national identity and citizenship, which came violently to the fore during the crisis, are still unresolved. And intercommunal violence continues, as seen in March and April both in Bambari in the centre of the country and between herders and farmers in the north west.

Today, national reconciliation and social cohesion have become much-repeated slogans.

More than anything reconciliation needs a strong political push at the national level. In this regard, much can be learned from the Pope’s visit to Bangui in November 2015. Hundreds of citizens of all denominations followed the Pope on his walk from the central mosque to the stadium, demonstrating that it is possible to remake connections with the population by going out to meet them. In March 2016, the new president’s visits to Obo in the far south east and to north-eastern Vakaga region, places where locals have long been cut off from the rest of the country and divorced from central authority, certainly send a positive message of national cohesion.

But much more will be needed to rebuild trust between the capital and the periphery. The government could make powerful symbolic gestures like holding the 1 December national celebration in the north east, from where many ex-Seleka combatants come. It could recognise Muslim celebrations as public holidays, satisfying a longstanding demand of the Muslim community, or create programs to integrate citizens from different regions into senior positions in the civil service. Changing the relationship between Bangui where power is concentrated and the provinces is crucial. Touadéra’s proposed decentralisation policy is in line with the recommendations of the May 2015 Bangui forum on national reconciliation, but the state is still too weak and too poor to implement it.

Nevertheless, the state must invest time and energy in territory outside the capital. It could increase the time members of parliament spend in their constituencies, establish resident-ministers (who live in the provinces they represent), or fund local reconstruction committees which could bring together local authorities, economic actors and civil society.

Young people in CAR are less educated than their parents, making them more vulnerable to mobilisation by armed groups and manipulation by politicians.

To avoid further violent outbreaks, Touadéra should invest in education, a sector which, as former rector of the University of Bangui, he knows well and one that could be a powerful driver of stronger cohesion in society. To ensure CAR remains stable, he should make rebuilding the education sector, including in neglected regions, a national priority. The president and prime minister’s former university positions will certainly be assets in this regard. The education sector has been in decline for a long time. Young people in CAR are less educated than their parents, making them more vulnerable to mobilisation by armed groups and manipulation by politicians. Even before the crisis, the education budget was dismal. In 2008, it accounted for only 15 per cent of expenditure (excluding debt servicing), compared to 28 per cent in 1996. Teachers were poorly qualified and badly paid and many failed to show up for work. Classes were often taught by parents on a voluntary basis. The crisis that began in 2012 dealt an additional blow to the sector, forcing many schools throughout the country to close.

As the Global Partnership for Education, a multilateral financing mechanism for primary and secondary education, prepares a review of the education sector, international partners and the education ministry should focus on long-term goals. They should develop a ten-year sector-wide plan which includes rebuilding destroyed schools, creating training centres for teachers, increasing their salaries and capacity building programs for government departments responsible for the education system. The government should also review the curriculum, and focus on post-conflict education by including courses on intercommunal tolerance and reconciliation. Psychosocial services should also be offered out of school to children who have experienced trauma. Finally, alternative education and training pathways should be developed for young people who have never been to school, including those who joined armed groups.

A Strategy to Help Refugees Return Home

During his first official visits to neighbouring countries, the new president spoke several times about CAR’s refugee problem – an essential piece of the national reconciliation puzzle. Today, there are some 466,000 refugees from CAR who have found safety in Cameroon, Chad and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and some 421,000 internally displaced people – together about one fifth of the population. The permanent relocation of Muslims fleeing attacks in the west by the anti-balaka (created as self-defence groups, many of the anti-balaka attacked Muslim communities while some others turned into banditry) to cities like Bambari, Bria or Ndélé in the east where ex-Seleka hold sway has in some cases changed the demographic balance in those places. The crisis has also created ethnic or religious borders within some cities and transformed formerly mixed neighbourhoods into religiously-homogeneous ones, such as the ones on the edge of PK5 district in Bangui. The refugee situation is even more problematic. There is still no overall strategy for accompanying and supporting refugees who want to return, which could cause tensions in the future.

In some cities like Bossangoa the hostility of Christians and animists toward Muslims makes their return impossible for now.

Refugees are reluctant to return primarily because they feel it would be too dangerous – justifiably so – and because they have lost property and land. Some have started coming back: traders who fled to Chad are returning to Bangui and, more cautiously, to the west, and some Fulani herders are going back to Boali, about 100km north of Bangui. But in some cities like Bossangoa the hostility of Christians and animists toward Muslims makes their return impossible for now. In the west several houses belonging to Muslims have been occupied or destroyed. Buying houses and land in the provinces is often informal, validated only by neighbourhood chiefs and sometimes the mayor, without official documentation or registration. The partiality of some neighbourhood chiefs and communal pressures on them could make it more difficult for the original owners to reclaim their properties. In Bangui, while many Muslim traders have gone back to work in PK5, in other markets, such as those in the “combatant” neighbourhood, young residents have taken over the trading areas formerly held by Muslims and returning Muslims have had difficulty getting back their business permits.

With the help of NGOs and UN agencies, the authorities should propose a pilot program to protect Muslim properties in select cities in the west, security permitting. They should also find out where refugees in Cameroon or Chad wish to return to and then engage with local authorities to determine where and under what conditions this would be possible. On this basis, the government, with donor support, should propose a plan to provide socio-economic support to returning refugees wishing to resettle and pick up their lives. Mending the communal rift requires reactivating the economic exchanges that existed before the crisis, which were the foundation of social relations between communities.

Fighting Impunity

In his inaugural speech the president underlined that the fight against impunity was a central concern. Citizens demand justice, as numerous testimonies collected in consultations before the Bangui forum made clear. While essential, it will be hard to achieve. In twenty years of successive crises, deadly rebellions and violent uprisings by the presidential guard, only a handful of individuals have been brought to justice and armed groups remain strong. This near-total impunity is the result of a longstanding political practice that has rewarded violence and favoured political over judicial processes, and of a judicial system now in ruins.

Before the crisis, CAR, a country of almost five million people, had only 129 magistrates and the judiciary’s budget was meagre. The situation has further deteriorated as many courts and police stations were destroyed during the violence. Prisons, police stations and detention centres are severely underequipped and the entire penal system needs rebuilding. Donors (including the European Union and the UN Development Programme) have helped repair the justice sector and the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) has arrested some criminals in temporary emergency measures. As further evidence of the challenges ahead, however, arrested militia members have sometimes been released for lack of evidence. Today, out of the three appeals courts in CAR empowered to try serious crimes (in Bangui, Bambari and Bouar), two have almost stopped functioning. In Bambari part of the justice system is still run by armed groups, whose members loiter just outside the court. In Bouar, as in most of the 24 provincial courts, magistrates are rarely present: “magistrates prefer to stay in Bangui either out of comfort or fear of retaliation”, an expert explained.

Countering impunity must go beyond violent crime and address economic and financial crimes and state predation.

Some attempts have been made to put right the judicial system’s flaws. In September 2014, the office of the International Criminal Court opened an investigation into crimes committed since 2012, but has so far issued no arrest warrant. After almost one year since former interim President Catherine Samba Panza signed into law a bill to create a special criminal court comprising national and international judges, the court is still not operational, partly due to insufficient funding.

Countering impunity must go beyond violent crime and address economic and financial crimes and state predation, which played a major role in precipitating the crisis (see Crisis Group’s report, The Central African Crisis: From Predation to Stabilisation). In the past few years, only three or four high-level civil servants have been sanctioned for embezzling state funds, mostly money from international partners. Some of them have been given positions in other departments. To break with this system that contributed to the gradual collapse of the state, the new authorities should sanction harshly the architects of corruption and the judiciary should take responsibility for future cases.

The Thorny Question of Armed Groups

Touadéra took the reins of the country in a security context undoubtedly less explosive than when Samba Panza took control in 2014, but the situation remains worrying. The problem of armed groups is far from resolved. While their capacity is diminished, many have now branched out into rural banditry, multiplying criminal rackets in local markets. Ex-Seleka factions maintain a hold on large areas and disarmament is lagging; only a small minority of rebels have handed in their weapons in a pre-disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) program. Given this situation, the withdrawal of French Sangaris forces in 2016 (a smaller military force of 300 soldiers should remain) is concerning for several reasons. Of all the peacekeeping operations deployed in the country in recent years, the Sangaris mission, seen as a safety net for the capital, has undoubtedly been the best deterrent against violence. MINUSCA is unlikely to be able to compensate for the Sangaris’ absence and may find it harder to exert vital military pressure on armed groups.

The new authorities should break with the recent practice of legitimising armed groups. Although these groups never transformed into political parties, they are undeniably influential actors on the political scene. During the transition, international partners and the authorities opted for the usual compromise: negotiate and give armed groups political space. Several anti-balaka and Seleka leaders were included in the political process; Djono, Hissene, Wenezaoui, Leopold Bara and others were ministers even under the presidency of Samba Panza. At the July 2014 Brazzaville summit, the international community even demanded that these groups be more rigorously structured so that they become reliable interlocutors (though they never were). And international partners, including the UN, promised armed group leaders in 2013 that their combatants would be integrated into the army. These measures accentuated the very problems they sought to resolve by raising armed groups’ legitimacy and expectations.

The solutions must come from within the country and have strong national ownership.

Today, many militia leaders see DDR as a large-scale army recruitment operation, rather than an economic reintegration scheme for combatants. “DDR is a medical visit”, a well-known anti-balaka leader told us in Bangui, “those who are able-bodied join the army, and the minority left behind are offered another job”. One former Seleka leader who left the armed movement said “armed groups fantasise about DDR; many will be disappointed”. While Touadéra has already begun talks with these groups, he should tell them honestly that it is impossible to integrate their troops into the army. The international community should support this approach. Otherwise there is a risk of turning the army, which already includes some former rebels, into a medley of militia forces.

As highlighted in Crisis Group’s September 2015 report Central African Republic: The Roots of Violence, a strategy centred on DDR programs should be left behind in favour of a disarmament policy formulated around the wider fight against trafficking and major development projects to reduce the appeal of the war economy. As the latest clashes in April near Bouar demonstrated, control over resources, specifically precious minerals, is at the heart of the problem. MINUSCA should deploy international forces in the main diamond and gold mining sites to allow CAR’s public servants to take up positions in the provinces and eventually help to revive the Kimberly process certification mechanisms, even in the east.

Ending the crisis in CAR will likely be long and challenging. The solutions must come from within the country and have strong national ownership. While the government needs to set out the roadmap, the international community – avoiding the mistake of confusing elections with the end of the crisis – should commit to providing constant and long-term support.

Source link : https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/central-african-republic/central-african-republic-four-priorities-new-president

Author :

Publish date : 2016-05-10 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.