This report was supported by the Robert Bosch Stiftung and is part of a wider research and advocacy initiative on internal displacement.

Executive Summary

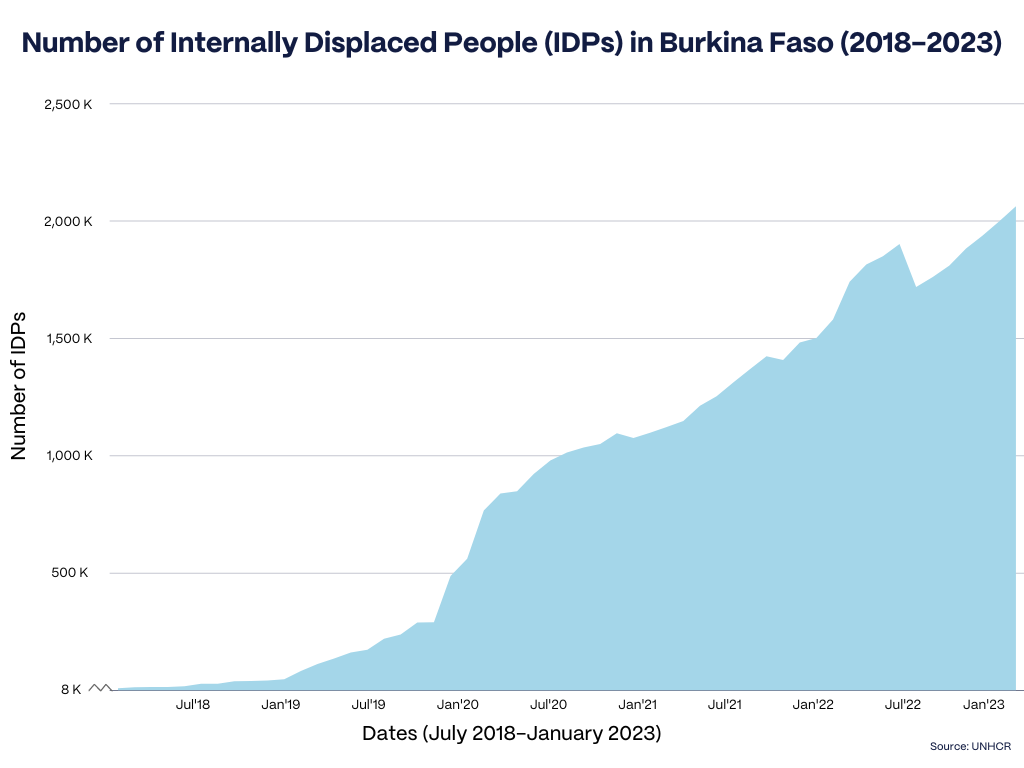

The West African country of Burkina Faso has been one of the fastest growing displacement crises in the world, second in Africa only to the mass exodus caused by the recent upheaval in Sudan. Clashes between armed groups and national security forces and attacks on civilians continue to cause massive displacement and humanitarian need.

Since 2018, more than 2 million Burkinabés have been internally displaced, and more than 36,000 have been forced to flee the country. In 2023, 4.6 million people will require humanitarian assistance—an increase of 1 million people compared to 2022. The most pressing needs, access to food assistance and access to water, will only worsen in the coming months as clashes block access to agricultural fields and armed groups systematically destroy water infrastructure.

The situation in the town of Djibo is particularly dire. For over a year, more than 350,000 people have been trapped under siege as armed groups limit the flow of food and other necessities by road. As a result, food insecurity in Djibo could reach catastrophic levels over the next few months—leaving hundreds of thousands of Burkinabé civilians on the brink of famine.

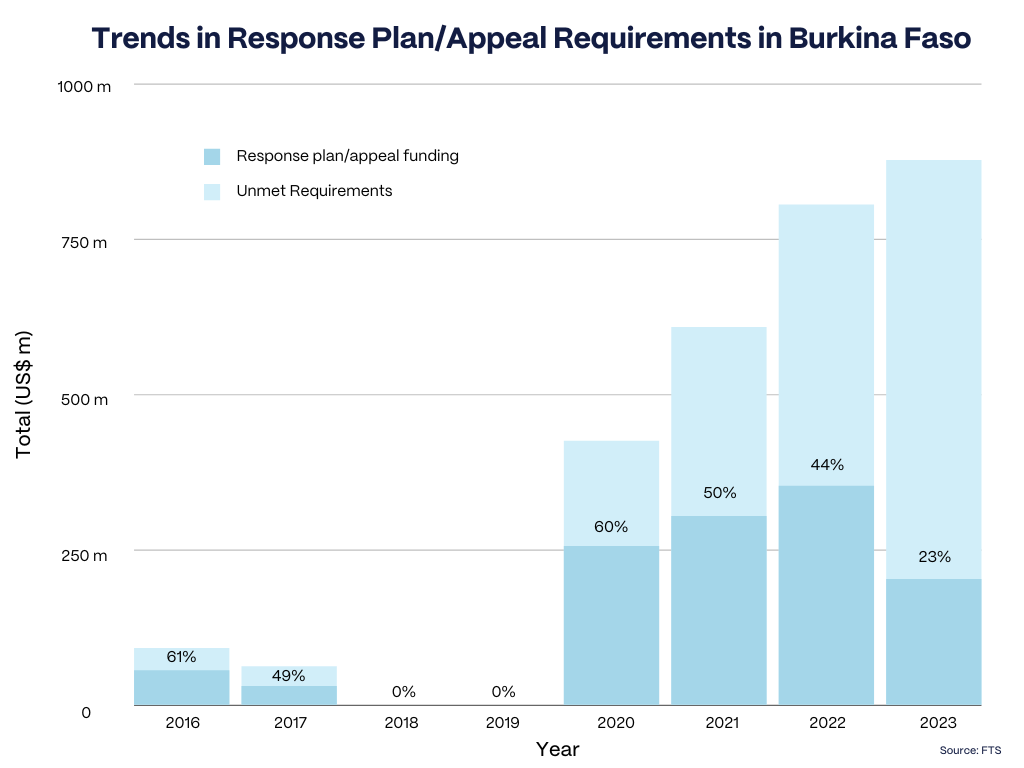

Yet, despite the deteriorating situation, the crisis receives few headlines, and international donors chronically underfund the humanitarian response. This combination of lack of attention and funding paired with growing need have led Burkina Faso to be dubbed the most neglected displacement crisis in the world.

Much of this neglect can be attributed to the myriad of global crises competing for limited international funds and a series of changing Burkinabé governments with little concern for their displaced citizens and a reluctance to share the full extent of the situation with the world.

The country experienced two coups in 2022, and three different governments have run the country since the outbreak of the conflict in 2018. All have censored aid groups and the media and obstructed a principled humanitarian response. National and international aid groups told Refugees International that the current Transitional Government, led by Captain Ibrahim Traoré as president, hinders access to populations in need and prevents the provision of aid for civilians living in areas controlled by armed groups. Some regional governors have also banned cash transfers, a key tool for getting aid to people in hard-to-reach areas. The national government has also intimidated aid organizations and restricted what relief groups say and do. In late December 2022, the head of the United Nations in-country, the Humanitarian Coordinator/Resident Coordinator Barbara Manzi, was expelled by the government without official explanation.

While aid groups and donors have made little headway toward improving the regime’s obstruction of humanitarian action, there is one potential bright spot: the government is on the cusp of passing legislation to enshrine the African Union’s Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa (known as the Kampala Convention). The government of Burkina Faso signed the Convention in 2009, but it has yet to be codified into national law. Recently, however, the government has been working with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the Protection Cluster, and other aid groups to draft a law that would codify the terms of the Convention and the government’s responsibilities into Burkinabé law. Although the law is still being revised by aid actors and Burkinabé authorities, government sources indicate that the law is slated to be passed before the end of the year. Momentum must not be lost to ensure this deadline is met.

Passage of such a law would not guarantee a change in the actions of the military regime that clearly contradict the spirit of the Convention. However, the codification of best practices would likely bring real changes among working level government ministries and civil servants that directly engage with displaced communities and humanitarian agencies. The Convention would also provide a roadmap for the government to change its approach to protecting Burkinabé civilians. Importantly, by codifying commitments it would also provide a helpful tool for diplomats and donor governments to engage the highest levels of government on displacement issues and to hold the national authorities to account.

Diplomats and donor governments should welcome this progress as a significant step—but recognize that much work needs to be done. To ensure the law’s adoption stays on track, donors should back UN agencies and aid groups in amplifying the true challenges in the country and push the government to not only adopt the law, but actually implement it in good faith through its policies and programs. In short, diplomats and humanitarians must take advantage of this opportunity as a first step toward making the displacement crisis in Burkina Faso just a little less neglected.

Recommendations

The Transitional Government of Burkina Faso must:

Fulfill its obligations under the African Union’s Kampala Convention. Burkina Faso’s Transitional Legislative Assembly must adopt the draft law when finalized to follow through on its commitments to the Convention—the continent’s main legal framework for the protection of IDPs.

Call on the governors of the Sahel and Centre-Nord regions to lift bans on cash transfers from aid groups to populations under siege.

Allow aid groups to adhere to humanitarian principles, including by refraining from pressuring aid groups or restricting access to populations in need. Since the onset of the crisis, all iterations of the national government have resisted or blocked a principled humanitarian response—often attempting to pressure aid groups to withhold aid to civilians in regions under the control of armed groups.

Cease targeted attacks on the country’s Fulani community by the Burkinabé forces. Since the onset of the crisis, government forces have indiscriminately attacked Fulani civilian communities—wrongfully portraying all Fulani community members as Islamist extremists. The attacks on these communities must cease.

UN agencies and humanitarian organizations must:

Identify, fund, and second experts to review the draft law to codify the terms of the AU’s Kampala Convention into Burkinabé law. As the draft law approaches its final version, those leading the process within UNHCR and the Protection Cluster must identify experts to review the document and create a strict timeline for this revision process. This process must be supported by international donors.

Donor governments must:

Rapidly disburse planned funding for the 2023 aid response, especially for food assistance and water, and increase overall funding levels. Despite global competition for funding, donors must not disengage as the need for humanitarian assistance and displacement continue to increase. In light of the pressing need for food assistance, especially in areas on the brink of famine, and the limited access to water as armed groups target water infrastructure, donors must prioritize these sectors of the aid response and quickly provide humanitarian groups with the necessary funding to mitigate the dire consequences.

Provide continued and increased financial support for the process of operationalizing the Kampala Convention. Funding must be immediately made available for the Protection Cluster to continue its work on the issue and not lose momentum. Such funding should go to support the process of reviewing the draft law as mentioned above.

Research Overview

To better understand the reality of displacement in Burkina Faso, Refugees International partnered with a local Burkinabé organization that interviewed displaced populations in five IDP host sites in the towns of Dori and Gorom-Gorom in the Sahel administrative region in April 2023. For security reasons, the local partner has chosen to remain anonymous. This report is further informed by remote interviews with representatives of UN agencies, as well as local and international non-governmental organizations working on providing humanitarian assistance. It also drew on previous research Refugees International conducted in Burkina Faso in 2022 and 2019.

Background

Over the last decade, the Central Sahel region has been wracked by violence, displacement, and humanitarian need. The crisis has spread from Mali to Niger and into Burkina Faso—impacting each country differently. While all three still struggle to quell the threat of armed groups and protect civilians along their shared borders, Burkina Faso has become the epicenter of the crisis, bearing the brunt of the region’s displacement and humanitarian needs since violence spread into its borders in 2018.

Frustration with the government’s inability to end the crisis and quash insurgent groups led to two coup d’états in 2022. In March 2022, Lieutenant-colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba ousted former president Roch Kaboré and was inaugurated as president, only to be overthrown six months later by Captain Ibrahim Traoré, now president of the Transitional Government. Although the transition period was only due to last until presidential elections were held in July 2024, officials are now hinting at the possibility of delaying the vote until peace is restored—however long that may be.

Despite the transitional government’s promise to bring peace to the country, non-state armed groups currently control 40 percent of Burkina Faso.

These groups, along with national forces and pro-government volunteer fighters continue to be accused of atrocities against civilian populations—including murder, rape, torture, and violent persecution based on ethnic and religious grounds (most often targeting the country’s Fulani Muslim minority). Most recently, Burkina Faso’s 3rd Battalion of the Rapid Intervention Brigade has been linked to the brutal massacre of more than 150 people in the northern village of Karma in late April 2023. Armed insurgents are also repeatedly accused of similarly brutal attacks.

Growing Displacement and Humanitarian Need

As a result of the cycles of brutal clashes, 2,062,534 Burkinabés are currently internally displaced people (IDPs) and 36,274 have sought refuge in neighboring countries. The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) currently estimates that $877 million will be required in 2023 to allow aid groups to provide humanitarian assistance to 3.1 million of the 4.7 million people in need of assistance. A UN staff member explained to the Refugees International team that Burkina Faso is facing a multi-dimensional crisis where insecurity, humanitarian need, rapid urbanization of the country and the drastic effects of climate change—impacting access to food and water, which fuel intercommunal conflict, all converge.

Halfway through 2023, only 26 percent of the necessary funds have been provided by international donors for this year’s humanitarian response. For all of 2022, the humanitarian response only received 43 percent of required financial support. According to REACH, 96 percent of displaced households surveyed in 2022 and 74 percent of non-displaced households had severe to extreme unmet needs in multiple sectors of need—whether it be food security, shelter, water, hygiene, and sanitation, protection, health, etc. These worrying statistics are the result of a worsening crisis and significant shortfalls in donor contributions year after year.

Over the course of 2022, the worsening security environment led to a significant reduction in humanitarian access. The situation in the town of Djibo, capital city of the Soum province in the country’s northern Sahel region, is the most extreme example of this dynamic. For over a year now, the more than 350,000 people residing in the town have been living under an armed group-imposed blockade—limiting the flow of food and other basic necessities. As a result, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) now warns that food insecurity in Djibo could reach IPC Phase 5 (Catastrophe/Famine levels) this summer. The organization, which provides early warning and analysis on acute food insecurity, calls on “donors, the government, and humanitarian partners [to] take immediate action to scale up food assistance and ensure full humanitarian access to prevent further loss of lives and livelihoods.

Needs in the Sahel Region

Burkina Faso’s Sahel administrative region—which includes the Oudalan, Séno, Soum, and Yagha provinces—has been hardest hit by the country’s ongoing crisis with 501,961 IDPs, followed closely by the neighboring Centre-Nord region which hosts 493,954 displaced Burkinabés. Moreover, 97 percent of households in the Sahel region are facing severe humanitarian needs and 70 percent are facing extreme needs. As of late April 2023, only 5 percent of those in need in the Sahel region have received the shelter assistance they so require. This leaves displaced people without the proper materials to build safe and adequate shelters.

Of the estimated 4.7 million Burkinabés in need of assistance across the country, 3.5 million will require food aid over the course of the year and 3.1 million will need water, sanitation, and hygiene assistance (WASH). While aid workers told Refugees International that this summer’s rainy season could help grow much-needed agricultural crops, much of the country’s breadbasket is in areas with the highest levels of insecurity—thus limiting access to fields. As a result, aid workers told Refugees International that this year’s harvest will be significantly below what it could have been if populations had access to their fields.

The war has decimated the water supply in many areas. According to an international aid worker, Burkina Faso, and its Sahel region specifically, are seeing “unprecedented attacks on water infrastructure by armed groups” described as “a systematic approach to deprive access to water and food.” Across cities in the Sahel, dams, reservoirs, pumps, and generators are being targeted by armed groups—cutting people off from basic life-sustaining services.

The internally displaced Burkinabés with whom Refugees International’s partner spoke in the Sahel towns of Gorom-Gorom and Dori underscored the severity of the situation. The vast majority of these displaced people said that few of their needs were being met. Most indicated that food and water were their primary concerns. In addition to aid, IDPs in both Dori and Gorom-Gorom focused on the need for better access to land for agricultural purposes, which would allow them to grow their own food and sell the remainder. Despite the pressing nature of these needs, international funds provided for these sectors of the response are woefully low: with food security only being 11 percent funded, and WASH interventions having received just under 8 percent of the required funds needed for the year. Given that the survival of many will depend on access to food and water, donors must mobilize funds for these aspects of the humanitarian intervention. This is particularly crucial as armed groups continue to target water infrastructure, and this year’s agricultural yield will be insufficient to provide for the country.

Displaced people in Dori explained that things are more expensive there compared to their villages of origin. This, coupled with the lack of humanitarian assistance, leaves them unable to meet their own basic needs. This frustration was echoed by displaced communities found in Gorom-Gorom.

A male IDP told the Burkinabé partner that they had to sell their cattle when they fled in order to have the resources to provide for themselves, but that this sum was not enough. He explained:

“We were poor of course, but now we are very far from our usual standard of living. We lack everything. And it’s not easy. And water is the real problem. We don’t think about showering anymore, we can hardly find any for drinking, even though we have sold all [our] cattle to avoid being burdened.”

A female IDP in Gorom-Gorom told Refugees International’s partner that “we are in shortage of everything—food, water—but we are alive, and that’s the main thing. Even if it’s not easy.”

One of the Burkinabé aid workers that met with displaced people stated that they could feel the IDPs’ “sense of resignation and powerlessness.”

The government has the responsibility to provide for its internally displaced citizens. However, IDPs in the Sahel appear to harbor few if any expectations of the government when it comes to responding to their basic needs. According to aid and development actors in the country, the Sahel region has received the least amount of government support and investment. But some indicated that they wanted the government to better provide education, shelter assistance or social housing, and finance income generating activities.

Fleeing Violence

Burkina Faso has also seen increasing levels of violence over the course of the last year, including the targeting of specific groups. This comes at the hands of both non-state armed groups and government forces. According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, there were 637 recorded instances of violence against civilians in 2022, and 348 had been recorded in 2023 as of late June. Among the displaced in Dori and Gorom-Gorom, the trauma of the violence they witnessed was apparent in the discussions they had with Refugees International’s Burkinabé partner.

A man who fled to Dori told the Burkinabé interviewer that because he is an Imam, he is “wanted by the armed groups […]. They systematically attack all religious leaders, especially us Imams.

They say that our ‘tolerant’ practice of religion is a betrayal. They are madmen, I’m sure. What they are doing is not in the name of Islam, I am sure of that too.

When asked about the reason for his displacement, a male IDP in Dori explained he and his family fled “because we were targeted for our ethnicity. And Dori is the town of the [Fulani], we felt that we could only feel safe in a town of our ethnicity.” They fled to Dori, more than 120 miles away from their village of origin instead of going to closer sites because they felt they would be safer among ethnic Fulanis. Displaced members of the Fulani community stressed that they are targeted by government forces and armed Islamist groups alike—leaving them feeling unsafe in many parts of the country.

While this Muslim ethnic group spans across Africa, they represent a minority in Burkina Faso and have long been neglected by authorities and marginalised from power.

Extremist rebel groups are known for taking advantage of the dearth of economic prospects and government services in Fulani communities in order to recruit Fulani youth. This trend has led to the inaccurate assumption that Fulani civilians are responsible for many of the country’s gruesome attacks—leaving them vulnerable to attacks from national forces. But the many communities who refuse to support the rebel groups are targeted with violence. This leaves Fulani communities vulnerable and prone to attacks from all warring parties.

Worryingly, the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect has reported that violent attacks on Fulani communities have increased since the second coup of 2022 that saw the ascension of Captain Ibrahim Traoré to power. National security forces must immediately cease targeted attacks on the country’s Fulani community.

Government Actions Hinder Humanitarian Response

Even as violence and other factors drive further displacement and need, the government is regularly putting up barriers to a more effective response. Various UN and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) lamented to Refugees International that since the onset of the crisis, national authorities (civil servants and national forces alike) and government-supported volunteer fighter groups have impeded humanitarian access to areas where armed groups were present. In general, aid responses are rooted in the core humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. Aid organizations must be permitted to report on the drivers of displacement and to respond in accordance with these principles. However, since the beginning of the crisis, the government has censored journalists, restricted access to displacement camps, and hindered the aid response. It has done so by intimidating and suspending aid groups, especially if their actions and reporting did not paint the government in a favorable way.

This stance has also contributed to the general lack of awareness of the levels of need in Burkina Faso, contributing to its status of neglect. Today, the Burkinabe government continues to prevent aid groups from adhering to humanitarian principles. Instead, the government pressures humanitarians to withhold reporting on the nature and scope of the crisis, as well as the government’s role in targeting civilians and fanning the flames of conflict. Moreover, national authorities continue to shirk their responsibilities to protect and provide for the country’s citizens, especially those living in areas controlled by armed groups. Numerous aid agencies told Refugees International that the government not only neglects those populations but also interferes with aid being provided in these areas. The government must allow humanitarian assistance to flow to all parts of its territory.

Regional Bans on Cash Transfers

In addition to the national-level authorities, regional authorities have also further complicated the humanitarian situation in the Sahel region. In January 2023, the governor of the Sahel suspended cash transfers—preventing aid agencies and others from transferring funds to those in hard-to-reach areas. Similar bans have been placed in the Centre-Nord and Est regions—though the governor in the Est region quickly lifted the restriction. While these moves may have been designed to cut off financial flows to insurgent groups, the bans prevent aid groups from transferring financial assistance to those in need. Importantly, aid actors told Refugees International that the ban also prevents the distribution of the government’s quarterly social assistance safety net funds—managed in partnership with the World Bank.

This decision forced relief groups to suddenly shift from cash transfers to in-kind distributions of food, shelter assistance, and other essential items. While groups have been able to adapt, this has come at a price given that in-kind assistance is more costly and logistically more difficult to implement in such an insecure environment.

National authorities have been working recently with the aid community in Burkina Faso to standardize the modalities of these transfers (schedules, amounts, and targeting/selection process of beneficiaries) to allay the concerns the governors of the Sahel and the Centre-Nord regions. These new standardized procedures must now be validated by the national government. While Colonel-Major Zoewendmanego Blaise Ouédraogo, governor of the Centre-Nord, has expressed a willingness to lift the suspension once these new terms of agreement are reached, his counterpart, Lieutenant-Colonel Rodolphe Sorgho, governor of the Sahel, has indicated that he has no intention of lifting the ban.

The role of the national authorities in addressing the humanitarian consequences of these bans on cash transfers is welcome. Their intervention could help restore access to badly needed cash. Once the new procedures are validated, the Burkinabé government should immediately call on both Colonel-Major Zoewendmanego Blaise Ouédraogo and Lieutenant-Colonel Rodolphe Sorgho to lift restrictions on cash transfers in the Centre-Nord and Sahel regions respectively.

Need for a Strong UN Voice

In late December 2022, the UN’s Humanitarian Coordinator/Resident Coordinator (HC/RC) Barbara Manzi was expelled from Burkina Faso by national authorities for “discrediting the country.” This decision is a prime example of the Burkinabé government’s intimidation of the aid community. The UN responded by stating that the Burkinabé government had no right to expel her from the country, and that only the “UN Secretary-General, as the Chief Administrative Officer of the Organization, has the authority to withdraw any United Nations official.”

An aid worker told the Refugees International team that the move to eject Ms. Manzi sets a dangerous precedent and highlights the continued shrinking space for advocacy, even when conducted privately and diplomatically.

According to aid workers with whom the Refugees International team spoke, the former HC/RC was known for being very careful about what she said publicly, and often opted to adopt a quiet diplomatic approach. Humanitarian staff bemoaned that even this managed to upset Burkinabé officials to the point of kicking her out of the country. An acting interim HC/RC was able to step into the role temporarily—and work to stabilize the relationship between the government and the UN community. With a new HC/RC Issa Sanogo soon to arrive in Burkina Faso, the UN, backed by donors, must make clear to the government that it cannot expel aid workers and UN staff as a form of intimidation and interference in the response.

Progress through the Kampala Convention?

The ongoing problematic government actions at the national and local levels as well as the incident with the HC/RC have shown the relative lack of leverage that humanitarian agencies have had in changing the response for the better. But there is one area where some notable progress has been seen, namely efforts to enshrine the commitments of the Kampala Convention into national law.

The African Union’s Kampala Convention—the only legally binding instrument in the world for the protection and assistance of internally displaced people—identifies the obligations of states to address displacement and calls for governments to adopt measures aimed at preventing and responding to internal displacement. While the government of Burkina Faso ratified the Convention in 2012, leaders, until recently, had made few efforts to operationalize it.

In 2014, in partial fulfilment of its terms, the National Assembly passed Law No. 012-2014/AN on the Prevention and Management of Risks, Humanitarian Crises and Disasters, which offers protection to those displaced by environmental disasters. But its passage has failed to fully protect IDPs, especially as it relates to civil documentation, social protection, and education and prohibiting arbitrary displacement as indicated in the Kampala Convention.

Since late 2020, at the request of the national government, UNHCR—through the country’s Protection Cluster—has led efforts to more comprehensively codify the terms of the Convention into Burkinabé law.

Over the course of 2022-2023, UNHCR staff, along with the national government’s Inter-Ministerial Committee in charge of this process, as well as representatives of the National Council for Emergency Relief and Rehabilitation (known by the French acronym CONASUR) have worked to draft a new law, which would enshrine the terms of the Convention into Burkinabé law. However, this process has been complicated and slowed down by the two coup d’états and changes in national leadership.

As of late May, those leading the process said that the draft law still needs to be reviewed by experts such as leads from each humanitarian Cluster and those with experience in operationalizing the Kampala Convention in other countries. Donors should help to identify such experts and provide financial support for their secondment to review the draft law in a timely fashion.

Once the final version of the draft law is complete, it will then be presented to the Transitional Legislative Assembly for their approval. Government sources have said that the law is slated to be approved before the end of 2023. As such, efforts must not lose momentum.

Beyond Superficial Adoption

Putting the Kampala Convention into action will require more than simply codifying it into law. The national government will need to change its approach to humanitarian action and allow aid groups to adhere to humanitarian principles. As someone working on drafting and passing the law told the Refugees International team “there is a missing link between the government adopting the law and them changing their approach to humanitarian aid.”

Many aid groups are concerned that passing the law will not make the government a good faith actor when it comes to aid organizations. This fear comes from years of different Burkinabe governments denying the extent of the crisis, silencing aid groups, targeting civilians, and fueling displacement, as detailed in Refugees International’s previous reports from 2022, 2021, and 2020. At the regional level, the suspension of cash transfers is another glaring example of officials interrupting aid.

The type of interference described above not only complicates the work of aid organizations but also violates the terms of the Kampala Convention. Article V (8) of the accord calls for State Parties to “uphold and ensure respect for the humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence of humanitarian actors.” Respecting this Article would require the State to allow aid workers to be transparent about the humanitarian crisis.

Although the role of national authorities in helping reinstate cash transfers should be applauded, the government must continue to shift its relationship with the humanitarian response and aid groups. Regardless of whether or not this shift occurs at the highest levels of Burkinabé leadership, the passage of the law will have an effect on day-to-day interactions between working-level authorities and displaced populations, providing legal backing and precedent for best practices. The law will also serve as a clear roadmap for the government to change its approach and can also serve as a tool to hold the government responsible for protecting and providing for its displaced citizens. Donors, aid agencies, and the international diplomatic community should encourage the national authorities to adopt both the letter and spirit of the law and to change their approach accordingly.

Conclusion

International inaction and the national government’s policies that complicate the delivery of aid in adherence with humanitarian principles continues to leave millions of Burkina Faso’s civilian population in situations of dire need without hope of comprehensive and timely assistance. While the armed groups that wreak havoc across the country complicate aid delivery, more robust humanitarian funding along with a change in approach—that adheres to the terms of the Kampala Convention—could change the aid landscape in Burkina Faso.

Featured Image: A mother and child await treatment at a children’s hospital in northern Burkina Faso. (Photo by Giles Clarke/UNOCHA via Getty Images)

Source link : https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports-briefs/a-crisis-of-displacement-why-burkina-faso-needs-the-kampala-convention/

Author :

Publish date : 2023-07-13 07:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.