A review of An African History of Africa: From the Dawn of Humanity to Independence by Zeinab Badawi, 532 pages, W.H. Allen (April 2024).

In his Lectures on the Philosophy of History (1837), Georg Hegel declared that Africa is “no historical part of the World” and that “what we properly understand by Africa, is the Unhistorical, Undeveloped Spirit, still involved in the conditions of mere nature.” His sentiments were echoed by esteemed British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who dismissed African history as “the unrewarding gyrations of barbarous tribes in picturesque but irrelevant corners of the globe,” proclaiming,

Perhaps, in the future, there will be some African history to teach. But at present there is none, or very little: there is only the history of the Europeans in Africa. The rest is largely darkness, like the history of pre-European, pre-Columbian America.

Such views remained uncontroversial in the West for a long time and were reflected in both high intellectual culture and in popular entertainment. Black Africans were frequently portrayed as barely clothed, over-sexed, flesh-eating savages who salivate at the sight of a European. The 1950 film King Solomon’s Mines, adapted from H. Rider Haggard’s 1885 novel, is a trailblazer for the ‘Lost World’ adventure genre. When the protagonists encounter an indigenous African tribe for the first time, they are gathered around a cauldron and the main female character remarks, “I’ve got the oddest feeling we’re going to get cooked in that pot.” This image of Africans as savage, cannibalistic hordes was to be very persistent in the European imagination.

Historically, Westerners have viewed Africa as tropical, black, primitive, mysterious, and obscure, and its people as tribal and preliterate, possessing neither historical records nor any sense of historical time. In this view, that part of the world was in perpetual stasis and socially, it had barely evolved since the Stone Age. Voltaire remarks of Africans, “a time will come, without a doubt, when these animals will know how to cultivate the earth well, to embellish it with houses and gardens, and to know the routes of the stars”—but that time had not yet arrived, he believed.

The point wasn’t that nothing ever happened in Africa. Trevor-Roper acknowledges that, “I do not deny that men existed in dark countries and dark centuries, nor that they had political life and culture, interesting to sociologists and anthropologists.” But Africa was ‘unhistorical’ for him because of his teleological view of history. The discipline, he writes, has “a purpose. We study it… to discover how we have come to be where we are.” In a world formed by “European techniques, European examples, European ideas,” this purpose could only be achieved by studying Europe. For Trevor-Roper, although African societies come and go, wars are fought, conquests occur, dynasties are established and overthrown, it’s all meaningless as there is no point to it, no direction. Africa, he believed, made no major contribution to human progress and only became relevant to world history when Europeans set foot there and set a process in motion whose apex was the Berlin conference of 1884. Anything before that was irrelevant, a mere chasm.

Few people nowadays would accept this assessment. In any serious modern history of human civilisation, ancient Egypt and North Africa feature prominently. Nevertheless, in almost every self-proclaimed ‘History of the World,’ sub-Saharan African civilisations are barely mentioned beyond a token acknowledgement that “humanity was born in Africa.” It’s not surprising then that there is widespread ignorance of African history even among highly educated people.

W.E.B. Du Bois was fond of the Latin expression semper novi quid ex Africa (‘there’s always something new coming out of Africa’). It was most associated with the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder, who uses the phrase in his Natural History to allude to the continent’s supposed abundance in mythical flora and fauna. But for Du Bois, Africa was significant chiefly for its contributions towards human progress. In the latter years of his life, until his death in 1963, Du Bois worked tirelessly on his mammoth Encyclopedia Africana, which he hoped would put to bed the idea that Africa was a tabula rasa, a land without history. He writes that from Africa’s “dark and more remote forest vastnesses came … the first welding of iron … agriculture and trade flourished there when Europe was a wilderness.” He argued that the knowledge of Africa’s historic achievements was erased by the process of European colonial conquest and domination, for which the idea of Africa as a “dark continent” provided a rationalisation. Thus, he writes, “‘color’ became in the world’s thought synonymous with inferiority, ‘Negro’ lost its capitalization, and Africa was another name for bestiality and barbarism.”

Zeinab Badawi’s An African History of Africa is very much in the same vein as Du Bois’s project. It advertises itself as a definitive corrective to old, prejudiced Eurocentric narratives about Africa. Hence the bulk of the book focuses on precolonial Africa. Born in Sudan and raised in England, the 65-year-old Badawi has had a very accomplished career as a broadcast journalist for Channel 4 News and the BBC. Since 2021, she has been president of SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) at the University of London. This, her first book, developed out of a nine-part documentary series for BBC World News released in conjunction with the UNESCO project General History of Africa (GHA), which aims to promote in-depth research into Africa’s heritage. “Everyone is originally from Africa and this book is therefore for everyone,” is the appropriate opening line of Badawi’s impressive book.

Barefoot Over the Serengeti: A Visit with David Read

Having lived and worked in rural East Africa for 16 years, I find that Read’s stories ring true, whereas Hemingway’s ring hollow.

Badawi acknowledges her indebtedness to many African scholars. Her aim, she writes, was to produce a history of Africa that is neither dominated by accounts of slavery, Western imperialism, and colonialism, nor resembles the descriptions “written mostly by Western historians, missionaries and explorers.” “Africa’s history is more than that,” she asserts. While the Atlantic slave trade and European colonialism undoubtedly exerted a profound influence on many modern African societies, to view African history as simply the history of slavery and colonialism would be as facile as to reduce German history to that of Nazism. Thankfully, we have much more extensive knowledge about premodern African civilisations than we had in the past and that body of knowledge is continually increasing, although, as Badawi notes, archaeological investigations that could uncover more about African history are often stymied by lack of funding, poor local infrastructure and political instability that might endanger researchers—factors that help exacerbate the widespread ignorance about African history.

Most lay people—including many Africans—would probably struggle to name an African monarch beyond, perhaps, Tutankhamun. Badawi recounts a story of an unnamed former African president who told her that “he was better able to list the names of English medieval kings than those in Africa.” Ancient Egypt is perhaps the only African civilisation to have always occupied a prominent place in the Western imagination. Renaissance painters used Egyptian symbols and hieroglyphics in their work, while Napoleon’s 1798 expedition to Egypt ignited ‘Egyptomania’ across the West. Egypt has also enthralled Afrocentrists, who view it as a prime exemplar of a ‘black’ civilisation. Hence, the frequent efforts to portray Cleopatra as phenotypically ‘black’ (sub-Saharan African) despite her Greek-Macedonian heritage. Such quarrels over the ‘race’ of the ancient Egyptians are anachronistic: ancient Egypt was a cosmopolitan civilisation in which people with a wide range of different skin colours and phenotypes would have co-existed. Ironically, the black nationalist trend for depicting Egyptians as black follows a Eurocentric narrative of African homogeneity but paints it in blackface—thus neglecting the underrated achievements and fascinating histories of other ancient sub-Saharan civilisations.

It is certainly true that ancient Africa contained numerous nomadic pastoralist societies like the Masai Mara. But Badawi’s book is sprinkled with examples of ancient civilisations that developed settled agriculture, trade, and literacy and produced impressive achievements in sub-Saharan Africa beyond the Nile. For instance, the Kushites, in modern-day Sudan, built almost a thousand pyramids, 250 of which are still standing—more than currently exist in Egypt. They contain elaborately decorated treasures bearing witness to a long tradition of craftsmanship. Their hieroglyphics have yet to be deciphered. The Kushites traded as far afield as China and India and the cultural influences of other civilisations, especially of Greece, can be seen in their architecture.

Thanks to the Egyptocentrism of so many scholars, the history of ancient Sudan has long been obscured. Historically, racism led archaeologists to assume that the natives of the Kush region couldn’t have developed a civilisation of their own and that their civilisation must have been the creation of immigrants from Egypt. Badawi notes that even many Sudanese are ignorant of ancient Kushite history. But although Kush and Egypt shared some cultural affinities and mutual influences, they were very distinct in terms of language and cultural practices. The Kush empire was a regional superpower for most of its existence and was of such significance that some of its kings are namedropped in the Bible.

Aksum, in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, is another example of a glorious African civilisation that was literate, employed advanced agricultural methods, used gold coinage, and traded with other civilisations. It was the second place after Armenia to adopt Christianity as its official religion. Aksumites imported goods like wine and glassware from the Mediterranean and China. Aksum was particularly famous for its unique churches, which were hewn and chiselled out of solid basalt rock by hand. As Badawi rightly notes, they “represent an extraordinary achievement of engineering.”

When 19th-century Europeans encountered the network of stone structures and monuments in Great Zimbabwe in Southern Africa, they viewed them as too advanced to have been created by Africans, who were still thought to be at a primitive, even prehistoric stage of human development, incapable of building anything more complex than a mud hut. Various theories were proffered as to who built them: Portuguese explorers, Arabs, Persians, or Chinese—everyone except the indigenous population of Southern Africa. The white Rhodesian regime led by Ian Smith censored books on Great Zimbabwe, especially if they said that the indigenous population were responsible for the monuments. The current scholarly consensus is those stone buildings were constructed by the Shona people in the late medieval era as the centrepieces of their trading empire.

West Africa also contained wealthy and sophisticated kingdoms and empires connected to the trans-Saharan trade networks. These kingdoms included the Ashanti empire in modern-day Ghana, and the Benin empire in modern-day Nigeria. The complex network of walls and moats erected in the 15th century with which the Benin capital was fortified, fascinated European explorers. They were destroyed during the British conquest of Benin in 1897, at which time the Benin bronzes were taken and displayed in museums across the West.

The greatest of all the West African empires was probably medieval Mali. Timbuktu, notorious in legend as the epitome of a mysterious, faraway place, was a renowned centre of trade and learning whose university, established by Mansa Musa, attracted scholars from across the Muslim world to study not just Islamic theology, but also history, rhetoric, law, science, and medicine. While he was travelling through Mali in the mid-14th century, Ibn Battuta observed that Malian Muslims had a “zeal for learning the Qur’an by heart”—though he was shocked by the fact that “their women show no bashfulness before men and do not veil themselves.”

Badawi dedicates a lengthy section of the book to Mansa Musa (1280–1332), whom she uses as an example of how Sub-Saharan Africa was integrated into world affairs. At a time when most of Europe was suffering from the ravages of the Black Death, Musa was one of the wealthiest individuals on Earth. He flaunted this wealth during a lavish Hajj pilgrimage in 1324–25, by travelling with an entourage of 12,000 slaves and 500 personal servants, alongside a hundred camels, laden with 10–20 tonnes of gold. On his way back from Mecca, Musa stopped off in Cairo, where he spent so much gold that it caused the metal’s global value to fall by 25%. It took over a decade for its value to recover. When in 1375, a Catalan cartographer drew a map of the world, he labelled one of the major regions “Mansa Musa.”

The exorbitant wealth of empires like Musa’s did not emerge from a vacuum. Like most premodern societies, these African kingdoms were sustained by slavery and other forms of enforced labour—necessarily so, since those labourers mined and extracted the gold, salt and other resources that produced that wealth. Many of these kingdoms captured slaves and sold them to European traffickers during the Atlantic slave trade. As Badawi emphasises, one must appraise African history “not with fairy tales but with facts.” For almost all premodern societies, slavery and indenture were tragic necessities. Sustaining civilisation was an arduous task. History is not a morality tale, but a tragedy.

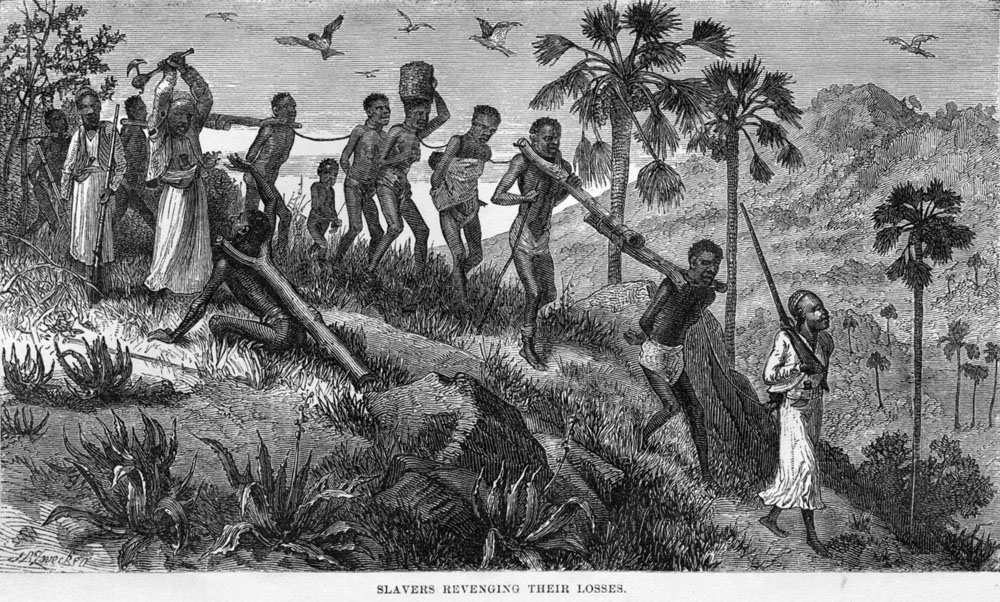

One result of the disfiguring effects of Eurocentrism on our knowledge of African history is that most people are aware of the Atlantic slave trade, but there is little awareness of the Indian Ocean slave trade, which, in Badawi’s phrase, was the “first international trade in enslaved Africans.” Between the 7th and 19th centuries, around 14 million Africans were enslaved and shipped to the Arab world, the Persian Gulf, and India. The 10th-century Arab geographer Al-Idrisi describes how “merchants would lure children to their ships with goods such as dates and then kidnap them.” One of the greatest slave revolts in history—on a par with Spartacus’s rebellion and the Haitian Revolution—was the Zanj revolt of 869–883 AD during which massive numbers of slaves and freedmen, mostly of Eastern African origin, who had been brought into Southern Iraq to drain the marshes and work on the plantations, launched an insurrection against the Abbasid caliphate that lasted 14 years before it was finally defeated.

Understanding Modern African Horrors by Way of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade

The modernizing elites of these groups then fought with the British during WWI and WWII, and demanded independence after the war, which they got.

Badawi also recounts the story of the women of N’Der in modern-day Senegal, who, in 1819, sent their children to hide in the fields and then organised themselves into a fighting force to repel a slave raid by Trarza Moors. The women scored a surprising initial victory, but the Trarza warriors soon attacked again. When defeat was certain, the women decided to commit suicide by burning themselves alive, rather than be enslaved. One of the most fascinating parts of Badawi’s book is her version of the story of Tippu Tib, the notorious Zanzibarian warlord, who established a slave trading empire for Zanzibar’s clove plantations, organising raids in Central Africa to acquire new slaves, whom he forced into the Indian Ocean slave trade.

Badawi’s book is particularly pertinent right now, as many disciplines debate the concept of ‘decolonisation,’ especially in history. The decolonialists argue that the history that is widely taught is Eurocentric and rooted in a triumphalist ‘Western narrative,’ which begins with classical Athens and Rome and climaxes with the European enlightenment, omitting the part that other regions of the world have played in the story of human civilisation. However, ‘decolonisation’ is unnecessary. We can achieve the aim of greater representation of Africa in world history by simply diversifying and expanding what is studied and taught. Books like Badawi’s will help in this project.

Too often, ‘decolonisation’ devolves into a quasi-nationalist enterprise, the point of which is not to enlighten inquisitive minds or do justice to history, but simply to bolster the amour-propre of ‘black people’ as a collective—as if we can’t understand world history unless we see ourselves narrowly represented in it. Thankfully, Badawi doesn’t stoop to this racial demagoguery—that is part of what makes her book so refreshing. The history of Africa, after all, isn’t the history of the ‘black race,’ but a vital part of the history of human civilisation. To view it as anything less would be an injustice to Africa’s history.

While Badawi’s book isn’t definitive, it is a great introduction to Africa for curious readers. It makes the continent’s dense history engaging and accessible to an Anglophone audience. This is a significant accomplishment. Badawi rightly begins her book by noting that “everyone is originally from Africa and this book is therefore for everyone.” The history of Africa is the history of humanity.

Source link : https://quillette.com/2024/07/16/africa-and-the-history-of-civilisation-zeinab-badawi/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-07-16 07:58:51

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.