Summary

Twenty years on from the Darfur genocide, mass atrocities are once again underway in Darfur. As a larger war continues to ravage the country of Sudan, a disturbing new wave of ethnically targeted killing has been unleashed by a militia descended from the groups that carried out the original genocide. But global action has been tepid and ineffective as the killings mount. With Darfur’s former peacekeeping mission now withdrawn, global diplomacy focused elsewhere, and wildly inadequate levels of aid, there is little in place to prevent the current atrocities from devolving into another mass-mortality catastrophe.

Many of the same atrocities seen in Darfur 20 years ago – including potential genocide – are unfolding again today. Once again, these atrocities are driving mass forced displacement and growing humanitarian needs. Most deaths to date have been due to violence, but without increased relief aid, many more people will die due to hunger and disease in the months ahead. With more than 10 million people displaced and half its population facing acute food insecurity – including nearly 5 million at the brink of famine – Sudan is now the largest displacement crisis in the world, and one of the worst humanitarian crises. Darfur, with rising hunger and the specter of genocide, has become the worst of Sudan’s crises.

Since April 2023, at least 13,000 people have been killed as a result of fighting between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). This is likely much higher, as the UN Panel of Experts on Sudan reports 10,000-15,000 deaths in El Geneina, Darfur alone. Attacks against civilians in Darfur by the RSF and allied militias have been marked by atrocities and led to a faster pace of displacement than during the first months of the infamous “first genocide of the 21st century” in Darfur two decades ago. Sudanese refugees arriving in Chad share accounts eerily reminiscent of the genocidal acts of the 2000s: house to house searches, looting and burning of villages, extrajudicial killings, mass graves, and widespread use of rape as a weapon of war, all targeting “Black African” tribes.

Refugees International visited eastern Chad in November of 2023, interviewing both newly arrived refugees and long-term residents of the refugee camps. The interviews made clear that mass atrocities are ongoing in Darfur, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and – once again – potentially genocide. Many refugees just arriving across the border reported severe abuses in the town of Ardamata, where an estimated 800–1,300 ethnic Masalit people were killed in the first two weeks of November.

It is also clear that failure to increase humanitarian assistance to eastern Chad and to secure access for aid into Darfur will lead to many more deaths, much as the death toll in Darfur 20 years ago shifted from direct killings to a phase of mass starvation and illness in a “genocide of attrition” in the years that followed. Yet, the humanitarian responses in Sudan, Chad, and for the region remain woefully underfunded at just around 40 percent of assessed needs in 2023.

In eastern Chad, the addition of half a million refugees to some 400,000 refugees who had been living in camps since the earlier mass killings in Darfur, has completely overwhelmed an already faltering humanitarian response. Chad, one of the poorest countries in the world, now hosts the most refugees per capita in all of Africa. UN humanitarian agencies and NGOs are scrambling just to provide the most basic of lifesaving needs – food, water, emergency medicine. They are unable to provide adequate shelter or more than minimal psychosocial support to a highly traumatized population, some 85 percent of whom are women and children. As one humanitarian worker described to Refugees International, the response in eastern Chad was the most under-resourced she had seen so many months into a crisis.

Urgent international action is needed on Darfur, as well as Sudan more broadly, to halt further atrocities. In December 2023, the United States made an official atrocity determination for Sudan, citing war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing. Now, the United States and other governments must back that determination with concrete measures. These should include diplomacy to address Sudan’s civil war and, specifically, the atrocities in Darfur. To lead these efforts, the United States should appointment a Presidential Envoy with knowledge of Sudan and familiarity with key players in the region, and adequate support staff.

Additional pressure must be placed, both on the warring parties and on those countries and companies supporting them through funding, political support, and provision of weapons. The United Arab Emirates’ (UAE’s) documented supplying of weapons to the RSF should be thoroughly investigated and met with appropriate censure and possible sanctions such as the blocking of future arms sales to the UAE. The United States and others must also increase support for evidence collection and accountability efforts. Finally, the United States and other donors should step up emergency support for Sudan and neighboring countries hosting Sudanese refugees, including Chad.

The bottom line is that Sudan is not “just” another civil war with an under-resourced aid response. It is one of the worst global humanitarian and human rights crises with the capacity to destabilize the region. The civilian population – especially in Darfur – is being subjected to mass atrocities reminiscent of the genocide at the turn of the century. Lives are being lost that could be saved. It is high time that the international community engage with the requisite urgency and commitment.

Recommendations

The African Union, Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), and countries with influence over the warring parties must:

Significantly strengthen diplomatic efforts to end the fighting in Sudan and secure humanitarian access through higher level political engagement. Prevention of atrocities in Darfur should be prioritized – as distinct from broader peace negotiation efforts – given the high risk of further atrocities and the poor prospects for a political solution in the near future.

The United States should appoint a well-resourced and appropriately empowered high-level Presidential Envoy for Sudan with experience and stature with key players in the region and the clear backing of the White House.

The United States and other countries of influence should support evidence collection and accountability measures in Sudan including through the Sudan Conflict Observatory, the UN Fact-Finding Mission for Sudan, the International Criminal Court, and any future credible accountability process within Sudan.

Hosts of ceasefire talks should prepare a monitoring mechanism to ensure protection of civilians, whether through the African Union, IGAD, a revitalized UN political mission, or the possible deployment of peacekeepers.

The UN Security Council and its individual members should:

Immediately investigate RSF General Hemedti’s command responsibility for the RSF’s atrocity crimes in Darfur and elsewhere. These investigations should trigger concrete actions to hold him accountable, potentially including a travel ban, designation for UN or U.S. sanctions, and potential referral to the International Criminal Court.

Investigate the role of the UAE in supplying weapons to the RSF – in violation of the UN Security Council arms embargo for Darfur – and follow with possible UN or bilateral sanctions such as denial of arm sales to the UAE.

Visit eastern Chad and invite Darfur refugees to present before the Security Council to raise awareness of the situation.

The government of Chad should:

Take immediate steps to halt the reported UAE shipments of arms from Chad into Darfur and commit to upholding the UN arms embargo on Darfur.

Halt the de facto policies restricting the number of refugees that can legally work, and also support and empower refugee-led efforts – like the peer groups and refugee doctor groups working together in the Adre refugee site – to allow greater capacity for the humanitarian response.

Streamline the process for providing visas and travel permissions for international humanitarian workers to operate in eastern Chad and allow the temporary establishment of offices, expansion of services, and use of more tents for food distributions in Adre transit site, until relocation is possible.

Further resource the efforts of government bodies including the National Commission for the Reception and Reintegration of Refugees and Returnees (CNARR), to increase capacity to provide services for new arrivals.

Donor countries must:

Support a massive scale-up in humanitarian aid. In Sudan, this should include greatly increased funding for UN appeals (which were funded at only 40 percent in 2023) and substantial funding for Emergency Response Rooms and other local mutual aid groups within Sudan. In eastern Chad, this must entail a surge of humanitarian support to meet basic food, water, health, shelter, psycho-social, and protection needs; emergency and development support for Chadian returnees and host communities; and a scale-up of cross-border delivery of aid from eastern Chad into Darfur.

Prioritize gender-based violence programming as soon as refugees enter Chad in line with principles laid out in the global Call to Action on Protection from Gender Based Violence in Emergencies and the U.S.-specific Safe from the Start ReVisioned Initiative.

Improve coordination of the humanitarian responses within Sudan and in surrounding countries including establishing a regional humanitarian country team forum and considering appointment of a regional humanitarian coordinator.

Methodology and Research Overview

A team from Refugees International, including a local Chadian humanitarian consultant, traveled to N’Djamena, Abeche, Farchana, and to several refugee sites in eastern Chad in November 2023 to assess the conditions and challenges related to the Sudan crisis response in Chad. The team spoke with newly arrived refugees from Darfur, refugees living for several years in the camps in eastern Chad, humanitarian workers, UN and government officials, and experts. The team visited dozens of refugees in Adre, Ambelia, Farchana, and Gaga. This research trip and report build on earlier reports based on trips to Sudan’s borders with Egypt and South Sudan since the crisis began in April 2023.

Newly arrived refugees from Darfur in the Gaga refugee camp in eastern Chad. Nearly 90 percent of new arrivals since April 2023 are women and children. Photo by Refugees International.

Background

Atrocities in Darfur are happening in the broader context of fighting across Sudan between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as “Hemedti,” that began in April 2023. That fighting has devastated the capital of Khartoum and several other parts of Sudan. The war has been marked by war crimes on both sides, including indiscriminate targeting of hospitals and other civilian infrastructure and widespread sexual violence.

This report focuses on the situation in Darfur, where 2.3 million people have been displaced, and on neighboring eastern Chad, into which more than 500,000 people have fled since April 2023. For more on the general situation and that of refugees and returnees in Egypt and South Sudan, see Refugees International’s earlier reports and statements.

The violence in Darfur is linked to the broader war in Sudan, but in many ways is also distinct. In Darfur – home to Hemedti’s tribe and the main base of RSF support – fighting between the SAF and RSF has occurred in parallel to a massive assault on the civilian population. RSF and allied militias, largely identifying as “Arab” have targeted non-Arab tribes like the Masalit (dubbed pejoratively by the perpetrators as “Black Africans”). Decades of conflict and ethnically charged rhetoric are driving attacks that go beyond military targets. The RSF and allied militias are seeking to control areas held by the SAF, but continuing attacks on civilians after SAF forces have withdrawn.

The atrocities of today echo the ethnic violence of the past. The RSF is largely descended from the Janjaweed Arab militias known as “devils on horseback” from twenty years ago. The rhetoric of targeting “Black Africans” is being repeated. And many of the attacks are the same. But there are also several differences in the nature of violence today that have implications for how to address it.

One big difference is that twenty years ago, the Sudanese Army was allied with the Janjaweed, supporting them with weapons and through aerial bombardments and attacks by helicopter gunships. Most attacks were on villages while urban areas of Darfur were largely controlled by the Sudanese Army and not subject to Janjaweed attacks. This enabled internally displaced people to cluster around the major cities to seek safety and access services. The Janjaweed of two decades ago was also largely made up of fighters on horseback and camels.

Today, the SAF and RSF are enemies. While SAF’s planes and helicopters no longer terrorize Darfur’s skies to the same extent, the abandonment of Darfur’s urban areas by the SAF leaves the urban populations defenseless before the RSF and allied militias. This has meant more urban displacement and disruption of trade and markets – and also left fewer safe areas for IDPs. The RSF and its militias are also better equipped than their Janjaweed predecessors. Today’s “devils on horseback” are accompanied by military vehicles, cars and trucks, and motorbikes and arrive much more quickly and without warning. The result has been a new brand of atrocities derived from those of 20 years ago. The implications are that suggested solutions of the past, such as calls for no-fly zones, are not as applicable, while others like addressing urban displacement and disrupting weapons supplies become even more important.

The response of the international community has also been more muted than in the past. The United States and Saudi Arabia have hosted a series of ceasefire talks, later including the African Union and East Africa’s Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). These talks have led to agreements on paper to respect international humanitarian and human rights law and to allow access for humanitarian aid, but with little practical effect or tangible change on the ground.

The United States has sanctioned several individuals and military-affiliated companies tied to the fighting, including Hemedti’s brother, a high-level RSF leader. The United States has also supported evidence collection and accountability efforts through the Sudan Conflict Observatory and supporting the establishment of an independent Fact-Finding Mission for Sudan. But U.S. diplomatic engagement has not risen to the highest levels, limiting the ability to influence the parties to the conflict and other countries of influence including Egypt and the UAE, who are backing the SAF and RSF respectively. Beyond the United States, action at the UN Security Council has been blocked by some and undermined by others. The UAE sat on the Security Council through 2023, but has – according to independent media investigations – been supplying weapons to the RSF, in violation of a pre-existing arms embargo on Darfur passed by the Security Council. The UN Panel of Experts on Sudan found these allegations to be credible and listed several accounts from sources in eastern Chad and Darfur of weapons deliveries.

The humanitarian response to the crisis has been largely underfunded. The 2023 humanitarian response plans for Sudan and for Chad were funded at only 40.8 percent and 39.7 percent respectively. Humanitarian access inside Sudan has been heavily restricted and Sudanese authorities have placed bureaucratic burdens on aid workers including stalled visa and travel authorizations. In eastern Chad, the government and host communities have been at the forefront of providing assistance but face their own economic strains and lack of resources. Chadian authorities are also concerned about the risk of conflict spilling across the border.

This report bears witness to the atrocities reported by refugees in eastern Chad and highlights the humanitarian situation and risk of both further atrocities and increasing deaths due to hunger and disease.

Kamisa, a woman from Ardamata in west Darfur just arrived across Sudan border in Chad. When RSF and allied militias looted, burned her town, killing many because of tribe, she took only her 5 month old. Photo by Refugees International.

Kamisa, a woman from Ardamata in west Darfur just arrived across Sudan border in Chad. When RSF and allied militias looted, burned her town, killing many because of tribe, she took only her 5 month old. Photo by Refugees International.

Bearing Witness to Ongoing Atrocities

During Refugees International’s visit to eastern Chad, one of the largest episodes of ethnic cleansing to date was taking place in the Darfurian town of Ardamata, not far from El Geneina, the capital of West Darfur. The team interviewed dozens of refugees including several who had just arrived at the Chadian border, recounting numerous horrific stories of abuse. Refugees told of house-to-house searches by men in RSF uniforms alongside local Arab militias, looting, burning of homes, and summary executions of men and boys. Some women were taken away and raped. Those who fled passed through numerous security checkpoints where they were physically and verbally abused as their remaining possessions were stolen. Refugees told the Refugees International team that they were often asked about their tribe and told that the “black African” people must leave.

Kamisa Abdullah, a 30-year-old woman from Ardamata, told Refugees International that following the looting by the RSF and militias there were dead bodies everywhere. “They killed many people,” she said. After a few days of hiding, she fled because there was nothing else to eat. The five-month-old son she carried was all that she was able to take with her.

Rougaya, a 33-year-old woman, also just arrived from Ardamata, described the wives of militia going house to house to select dishes and other objects of value. She described seeing her husband shot in their home two days before. Unable to go out to bury him, they held a funeral in the home before fleeing. She further described militia burning homes and saw a blind woman thrown into a fire.

Ibrahim, a 65-year-old male from Ardamata, said that the militia called for men to come out of their homes, “beat Black people,” and killed boys as young as 15. His house was burned, and he saw an IDP camp burned. He witnessed a woman he knew get raped. “It’s a very difficult story,” he said, “I saw bad things, things I can’t even talk about.”

A 24-year-old woman interviewed by Refugees International said she was kidnapped for three days by militia. She said they did not rape her because she had already had three children and her captors preferred young girls aged 14-19. The militia killed one of her children.

In all, the UN estimates that more than 800 people were killed during the attacks in Ardamata over the first two weeks of November 2023. Local groups have reported more than 1,300 deaths. An estimated 10,000 fled across the border to Chad, while others fled to other parts of Darfur. Subsequent independent reports have further documented ethnically targeted executions and an “organized campaign of atrocities against Masalit civilians” in Ardamata.

A Pattern of Atrocities

Ardamata was not the first such massacre. Previous attacks on other urban centers in western Darfur including El Geneina and Misterei have been independently documented. Refugees International spoke with several refugees now in eastern Chad who had experienced this violence.

Nahila, a 19-year-old woman from El Geneina, described attacks by the RSF and allied militias in which boys as young as 10 to 12 years old were killed. She described seeing so many bodies in the streets that she had to climb over them to pass. She saw women taken away and others barely able to walk because of being raped. As she fled, the militia even took what food they had and burned it in front of them.

Fana Hamat, a 40-year-old mother, who left Ardamata three months earlier, described how Arab militia took her oldest son, age 17, at a roadblock. She pleaded that he was a student, and they took him to a militia leader. The leader asked to check his hands and felt that they were soft so said he was okay to go. She came back to the border in November, waiting for news of her brothers and found out from a neighbor that one was killed two days before.

Nuralddin Mohamed, a former businessman, fled attacks in Misterei in May 2023, during which he described seeing men lined up and shot or cut with knives. “They ask your tribe,” he said, “If you say Masalit, they kill you.” He survived by hiding but said his seven-month-old was shot in the leg by a stray bullet. “They attack us because of our skin, because we are Black.” He now volunteers at an emergency health clinic where he pointed out several other recently arrived children on crutches with bullet wounds.

Another man from Misterei described being caught among 46 men and forced to lie down with their hands behind their back then shot. He was shot in the shoulder and pretended to be dead for two days before someone was able to bring him to safety in Chad.

Noura Idriss, a 27-year-old woman from Misterei saw young children taken and burned in fires. “They want to chase all the black color out and take the land,” she said.

Many aid workers based in Chad with whom Refugees International spoke recounted similar stories from numerous refugees.

Atrocity Crimes

The crimes described by refugees fleeing Darfur fit the definition of what the United Nations defines as atrocity crimes, which include war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and ethnic cleansing.

War crimes are defined by the Geneva Convention and other international treaties as acts committed by individuals in the context of armed conflict against people or properties that include willful killing, torture, intentionally directing attacks against a civilian population or civilian objects, pillaging, committing rape, sexual slavery, and intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare, including by willfully impeding relief supplies.

Crimes against humanity are defined in international law as any of several acts committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack by a state or organization directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack. These acts include murder, extermination, torture, rape, sexual slavery, and other forms of sexual violence.

Genocide is defined in the International Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide as any of several acts, committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. These acts include killing, bodily harm, separation of children from their families, or the creation of conditions meant to destroy the group in whole or in part.

Ethnic cleansing, while not defined within international law, has been defined by a UN Commission of Experts as, “a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas.” Such campaigns may be marked by the same acts that constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Action and Accountability for Atrocity Crimes

The crimes described by refugees and further confirmed through the UN Panel of Experts on Sudan, independent reports and satellite analysis clearly include acts of willful killing, rape, impeding of relief supplies, as well as systematic attacks directed at civilians of a specific ethnic group that amount to war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing. Several acts of genocide (e.g. killing and causing serious bodily or mental harm of a specific group) have also clearly been committed. “Acts of genocide” may amount to genocide if the “intent to destroy” is proven.

It is critically important, however, that the world does not wait for a formal determination of genocide before intervening. A formal genocide determination is a lagging indicator – it tends to reflect violence that has already occurred rather than warn of what is coming. The legal “intent” threshold for genocide can be difficult to prove in real time, even as the effects of genocidal acts are evident. But that is all the more reason for aggressive diplomatic leverage now – when the warning signs are flashing – rather than only once genocide is formally proven.

And make no mistake – those warning signs are already flashing red. In December 2023, based on the available evidence, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken made an official determination that atrocity crimes are occurring in Sudan. The determination found that the SAF and RSF had committed war crimes and that the RSF had also committed crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Blinken also stated that the “determination does not preclude the possibility of future determinations” and referenced “the haunting echoes of the genocide that began almost 20 years ago in Darfur.”

Atrocity prevention experts warn that further atrocities may soon occur as the RSF seeks to consolidate control in North Darfur and east into Kordofan. The UN special advisor on the prevention of genocide has warned that the “the risks of genocide and related atrocity crimes in the region remain grimly high.”

The United States should back such determinations and dire warnings with concrete policy steps to surge diplomatic efforts, censure and sanction enablers of the violence, and to support the collection of evidence and future prosecutions.

Steps must be taken to increase pressure on the warring parties to cease further atrocities and respect international human rights and humanitarian law. Cessation of such atrocities must be a central part of any ceasefire negotiations. Diplomatic efforts should take place at the highest levels to reflect the gravity of the crimes. The United States should appoint a Presidential Envoy to engage countries in the region toward a cessation of hostilities.

The UN Security Council should censure and consider sanctioning actors who are enabling these atrocities, including through violation of the existing UN Security Council arms embargo on Darfur. If politics prevent the Security Council from acting, the United States and other individual countries should act bilaterally. For example, the role of the UAE in supplying weapons to the RSF in Darfur must be closely investigated. Rather than providing the arms used to commit atrocities, the UAE should use its leverage to press the RSF and allied militias to respect international humanitarian law.

Efforts to secure a ceasefire should also be accompanied by preparations for a monitoring presence including possible peacekeepers in Darfur and other areas at risk of atrocities. Depending on the outcome of ceasefire talks, this could come in the form of an AU observer mission, a revitalized UN political mission, peacekeepers, or an independent monitoring mechanism along the lines of the IGAD Joint Monitoring Mechanisms used in South Sudan. The United States and other countries should also increase support for the UN Fact-Finding Mission, the International Criminal Court, and any future credible accountability process in Sudan.

Finally, the effects of the atrocities committed to date must be mitigated and further death prevented by surging humanitarian support to affected populations, both within Sudan and across the border in neighboring countries.

Adre refugee site where most of the half million newly arrived refugees from Darfur have fled since fighting broke out in Sudan in April 2023. Photo by Refugees International.

Adre refugee site where most of the half million newly arrived refugees from Darfur have fled since fighting broke out in Sudan in April 2023. Photo by Refugees International.

The Humanitarian Fallout

The humanitarian effects of the conflict in Sudan have been devastating. Across the country 24.7 million people, more than half the entire population, are now in need of humanitarian assistance, including nearly 5 million on the brink of famine. The violence has cut off trade, decreased supplies, caused price increases, and devastated medical facilities. Fighting along with poor network and phone connectivity, lack of cash, and bureaucratic impediments by both sides – including delays and denials of visas and travel permissions – have disrupted outside aid.

In late December 2023, the fighting spread to Al Jazirah State, considered the country’s breadbasket, as the RSF took control of the state’s capital Wad Medani, a key humanitarian hub. The fighting was marked by further atrocities and looting of humanitarian warehouses and supplies. The result has been further shrinking of humanitarian access amid growing need.

According to the latest Humanitarian Response Dashboard, through the first seven months of the conflict, 163 humanitarian partners provided life-saving aid to some 4.9 million people and agricultural and livelihood support to 5.7 million people across Sudan. But this remains far below the level of need for 2024 (estimated at 25 million people in need of aid). Martin Griffiths, the UN Emergency Relief Coordinator, warned in January 2024 that “the bleak reality is that intensifying hostilities are putting most of [those in need] beyond our reach.”

Sudanese civilians have come together in various parts of the country to provide food, water, medical assistance, and shelter. This includes Emergency Response Rooms and other community-based mutual aid groups, many of which grew out of the neighborhood resistance committees that organized protests ahead of the overthrow of Sudan’s longtime dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019. While a bright spot, these groups face several challenges, including a broken banking system, threats from warring parties accusing them of supporting the other side, and overall limited resources. The groups are mostly funded by local and diaspora donations, with limited support from international aid groups. Finding ways to further support these groups with flexible funding and training could greatly enhance the levels of aid throughout the country.

Access constraints are especially felt in Darfur, far from the hubs for international aid and where atrocities have disrupted local mutual aid groups. From within Sudan, aid comes from a hub in Port Sudan in the far east of the country and must be transported hundreds of miles to reach many parts of the country and more than 1,000 miles to reach Darfur. Convoys are often turned back at the last moment. In December 2023, the World Food Program (WFP) reported that it had only reached Khartoum once in the last three months. A road convoy carrying medical supplies from Kosti in White Nile State in November took five days and was the first such convoy to reach Central Darfur since the start of fighting.

As in other parts of Sudan, NGOs operating in Darfur have reported arbitrary denial of access, looting of aid supplies, and attacks on civilian infrastructure, including medical facilities. Refugees arriving from Darfur told Refugees International about the scarcity of food due to the inability to plant and harvest crops, destroyed markets, and looting.

One solution is to provide cross-border aid into Darfur from neighboring Chad. For the past several months, UN agencies and INGOs have been transporting aid to the Chad-Sudan border negotiating access and delivery with local and regional leaders in Darfur. They have done so with the permission and cooperation of Chadian authorities. Humanitarian officials told Refugees International that since August 2023, more than 200 trucks have delivered more than 7,600 metric tons of aid to an estimated 2.4 million people in West, Central, and North Darfur. Yet this remains a “drop in the ocean” in relation to the needs. The attacks in Ardamata and fighting near the border in December caused a temporary suspension of this aid – that has since lifted – and nearby fighting remains a concern. But humanitarian officials with whom Refugees International spoke said it was more a lack of resources than operational constraints holding back further delivery of aid, suggesting there is significant room for scaling up. Funding for the humanitarian response in Sudan only reached 40.8 percent of what was needed in 2023. Rapid scaling up of funding will be needed to begin the lengthy procurement and delivery processes to reach Darfur from Chad before further areas approach famine levels.

One risk with cross-border efforts is the potential for manipulation of aid by the RSF, allied militias, or local actors. There is a history of such practices in Sudan, and an ongoing risk that the parties responsible for ethnic cleansing may seize or deny aid along ethnic lines. These risks must be measured against the dire needs. A humanitarian official involved with the cross-border delivery assured Refugees International that no such misuse had been seen to date and that the red lines for aid delivery are clear to relevant authorities in Darfur, including RSF and local authorities. The Humanitarian Country Team has endorsed Joint Operating Principles (JOPs) that lay out requirements for delivery of aid in line with humanitarian principles. This includes the insistence that aid should be delivered without military or militia escorts and without interference in the selection of beneficiaries based on need. But scaled up aid will require consistent due diligence to ensure that remains the case. UN agencies, backed by donor nations, must be clear with their interlocutors in Darfur that denial or diversion of aid meant for those in need will result in a cut off of aid and international censure.

Any scale up in cross-border aid will also need to be calibrated with an increase of aid for those who have fled to eastern Chad and are also facing great need. As will be detailed in the section that follows, these new arrivals join longer-term refugees and a host community already suffering from a lack of resources and economic opportunity. All of these groups will be understandably frustrated to see much needed aid rumble past in trucks headed to Darfur. Aid workers are concerned that this could lead to restrictions on cross-border aid by the Chadian government or threats by people in need of aid against relief convoys passing through these communities. Coordinating efforts within Sudan with those in or originating from Chad will be essential to managing these risks. Establishing a UN regional humanitarian country team forum and considering appointment of a regional humanitarian coordinator would help to address these issues.

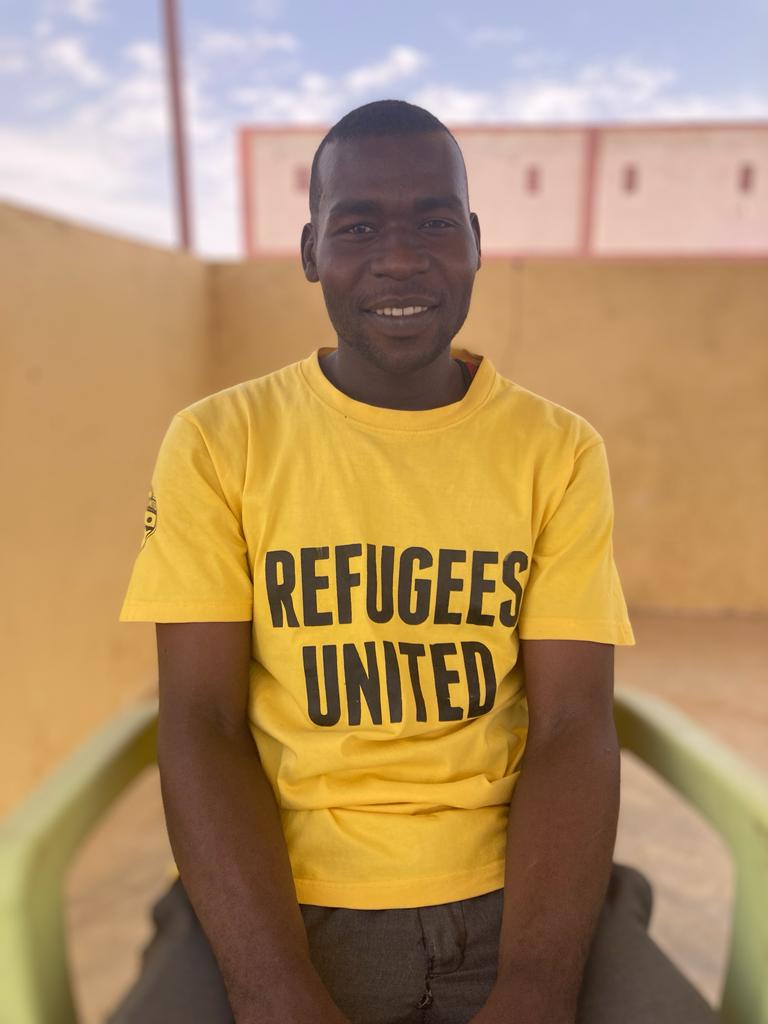

Mahamat arrived in the refugee camps in eastern Chad 15 years ago. He is now a soccer coach for Refugees United, providing guidance to young refugees. He says it’s important for him to support the community. Photo by Refugees International.

Mahamat arrived in the refugee camps in eastern Chad 15 years ago. He is now a soccer coach for Refugees United, providing guidance to young refugees. He says it’s important for him to support the community. Photo by Refugees International.

Eastern Chad

Even in places where insecurity does not constrain aid delivery, the survivors of atrocities are not receiving the support they need. In eastern Chad, the arrival of nearly 500,000 new refugees over the course of a few months has overtaxed an already severely under-resourced humanitarian response. Prior to April 2023, some 400,000 Darfuri refugees were still living in camps in eastern Chad after having fled earlier bouts of violence. Their food rations had already been cut and many humanitarian organizations had left. Just before the latest Sudan crisis, WFP reported that in 2022 rations had to be cut in half, resulting in 90 percent of refugees in Chad not receiving adequate food assistance. In addition, Chad is among the poorest countries in the world ranking at the bottom of the humanitarian development index. Now, with the new arrival of refugees, it has the highest ratio of refugees to host population in Africa. Chadian government entities like the National Commission for the Reception and Reintegration of Refugees and Returnees (CNARR) – the lead and primary partner with UNHCR in providing services and protection to Sudanese refugees – have done an admirable job but with far too little resources.

At the time of Refugees International’s visit, nearly eight months into the crisis, the response in eastern Chad remained at a chaotic emergency level. In Adre, the location where the vast majority of refugees cross into Chad, some 160,000 recent arrivals are living in mostly makeshift shelters, many lacking even basic plastic sheeting. Humanitarian workers with whom Refugees International spoke said they were struggling to provide the most basic emergency food, water, and medicine, let alone adequate shelter or protection services. As one humanitarian worker told Refugees International, seven months in, this was the most under-resourced response she has seen.

The impact of the lack of resources is severe across most sectors. As was apparent during Refugees International’s visit, the number of latrines and water and hygiene facilities are clearly inadequate. Proper shelter or livelihood opportunities are a luxury. Aid agencies are unable to support basic protection programs. For example, they are unable to provide water to potential volunteers who would spend the day out in excessive heat over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The lack of resources has also hampered UNHCR’s ability to register refugees, making it more difficult to track cases of vulnerability and to ensure efficient use of limited resources. The country director of a large humanitarian organization told Refugees International there are “meaningful, good efforts” being carried out, but the humanitarian footprint is virtually invisible because the needs are so high. Or as one humanitarian worker put it, “We know the gaps. There are just absolutely no means.”

The lack of protection and mental health resources are of particular concern given the demographics and nature of the violence from which refugees have fled. Some 85 percent of the new arrivals are women and children. Men are either unable or unwilling to flee to Chad. This is likely due to a number of reasons. The RSF and militia forces are blocking some men from crossing. Others are staying back to fight or to guard houses and tend to fields, or because they have been detained or killed. Many women lost husbands, often watching them killed in front of their eyes with no chance to bury them. Many children lost parents and experienced other traumatic events. Women have been the victims of widespread sexual violence. A doctor working with the refugees told Refugees International that the mental health challenge is huge, but there are hardly any resources and few people trained to address it. Given the outsized role violence against women plays in this conflict, donors must increase their funding for GBV prevention, mitigation, and response activities.

Funding

Despite acknowledgement of the atrocities taking place in Darfur and the resultant doubling of refugees in eastern Chad the response remains grossly underfunded. As of the end of 2023, the humanitarian response in Chad (covering eastern Chad and needs in other parts of the country) had received just 39.7 percent of what is needed. The Humanitarian Response Plan for Sudan had received just 40.8 percent. And the Sudan Regional Response Plan, aimed at assisting those fleeing Sudan to neighboring countries including Chad, was funded at just 38 percent. In the broader global context of growing needs and decreasing funding, this is, sadly, not uncommon. Overall, humanitarian plans were funded at just 39.3 percent globally. However, the crises in Sudan and Chad stand out for the level of basic needs going unmet and the dire prospects for further deaths due to hunger and disease in the coming months. The latest food security analysis for Sudan shows the highest levels of hunger ever recorded during the harvest season, leading WFP to warn of a looming hunger catastrophe. In eastern Chad, where instability is not a barrier to aid delivery, the relative cost-benefit of increasing aid, measured in potential lives saved, is immense. As one humanitarian official in Chad told Refugees International, “a small amount of money could make a huge difference here.”

Refugees Lead their own Efforts

In some cases, refugees themselves have stepped in to fill some of the gaps. For example, refugees have set up peer groups and at least one women-friendly center with nominal support from NGOs. Former social service workers in Darfur have come together to provide rudimentary services. A group of doctors among the refugees has also set up a makeshift pharmacy to try to supplement the meager health resources available through traditional humanitarian channels.

The presence of a significant number of highly skilled refugees, often fleeing urban areas of Darfur, has been a unique characteristic of the current wave of forced displacement compared to those of the past. However, Chad is not fully implementing its laws that allow refugees to legally work – meaning the talents of this population are woefully under-utilized. While the majority of newly arriving refugees come from agricultural backgrounds, they are accompanied by doctors, neurosurgeons, engineers, teachers, university professors, and high-level civil servants. Registration information has been limited, but a sample shared with Refugees International provides an interesting snapshot. In Ourang, one of the newly established camps, around 34,000 out of 45,000 registered refugees had no professional activities (presumably working in agriculture), 5,100 had secondary education, and 1,300 at tertiary education. UNICEF says it has identified 800 teachers. Chadian law allows for refugees to work, but humanitarian workers told Refugees International that the de facto policy is to restrict the number of refugees that UN agencies and NGOs can hire. Lifting these de facto restrictions and supporting refugee-led efforts can help to unlock greater capacity for a challenging response.

Manahim Yousef, a 24-year-old who studied at Khartoum University, was an English teacher in El Geneina before being forced to flee in April. She now teaches in the Farchana camp extension for new arrivals, receiving a small stipend. She told Refugees International there are many skilled women among the refugees, including bakers, tailors, and teachers, who just want the chance to work and support themselves.

Relocating Refugees Further Away from the Border

A priority of the humanitarian response to date has been to move refugees away from the border either to new or pre-existing camps. This has been driven both by overcrowded conditions and by security concerns that fighting could spill across the border. Chadian authorities have provided land for new camps, and UNHCR has provided sturdier shelters, latrines, and other vital camp infrastructure and already moved tens of thousands of refugees. However, challenges in finding adequate water have slowed these efforts.

As of January 2024, UNHCR had relocated more than 217,000 refugees from Adre and other sites and opened five new camps. However, humanitarian officials told Refugees International that tens of thousands of refugees were likely to remain in Adre over the coming months. At the same time new refugees continue to arrive. The latest UN planning numbers suggest as many as 250,000 more people will arrive in 2024.

While the need to move refugees further from the border and to avoid entrenching a more permanent presence in Adre is understandable, most of the 160,000 refugees will remain there in the near future. Donors must fund aid agencies to scale up their presence and service delivery at the border. For their part, Chadian authorities have insisted on rapid relocation of refugees and resisted anything that would hint at a longer-term presence of refugees in Adre, even to the point of refusing the setup of tents for food distributions. At the time of Refugees International’s visit, the only temporary tents were set up for relocation processing purposes. These were repurposed for some food distributions, but insufficient for most refugees who waited hours in the open heat. To better meet the immediate needs, Chadian authorities, supported by international donors, should facilitate interim expansion of services, establishment of temporary offices for humanitarian groups, and the construction of basic infrastructure like tents for food distributions.

Chadian Returnees and Host Community Tensions

Alongside refugees, there have also been more than 130,000 Chadian returnees who had lived for many years in Darfur and have now been forced to return to Chad. Many of these returnees no longer have family connections or places to stay in eastern Chad. As Chadians, they do not have access to refugee services, but have similar needs. IOM has set up a site for returnees that now houses more than 8,000 of the most vulnerable. IOM expects the total number of returnees to reach 150,000 by March 2024.

As new returnees and refugees arrive, or are moved to new locations, one of the challenges facing humanitarian responders and Chadian authorities will be moderating potential tensions between the host community and refugees as well as between refugees who have lived in the camps for years and newer arrivals. The lack of resources and the fact that only a third of pre-existing refugees receive aid while new arrivals receive blanket aid will be a source of tension. Meanwhile, much of the host community is poor and lacks adequate resources themselves. Local Chadians were the first responders to people fleeing Darfur. As refugees told Refugees International, many Chadians provided home cooked meals in the first days of the crisis. But as the crisis goes on tensions are rising. Some refugees reported being attacked when venturing out to collect firewood.

Aid for Host Communities

Host community tensions and growing frustrations among refugees and returnee populations over a lack of resources and services present a significant challenge. Humanitarian workers are trying to mitigate these challenges by ensuring that new water points, health clinics, and schools are available to the host communities and refugees. Aid workers are also seeking to kickstart development efforts alongside humanitarian action. As cross-border emergency aid is provided into Darfur and to newly arrived refugees, resources must also be scaled up in tandem and offered to longer-term refugees and the host community. Development funding for agricultural as well as professional opportunities must be provided alongside emergency aid to ensure resilience and social cohesion.

Conclusion

During the genocide in Darfur that began in 2003, an estimated 300,000 people were killed. At the start, most of these were deaths due to violence, but, in the end, most of the deaths would be due to illness and hunger that resulted from mass displacement and lack of access to humanitarian assistance. As conditions today continue to deteriorate, there is a real risk of return to the kind of genocide by attrition that killed the majority of victims of the Darfur genocide 20 years ago.

To stem further tragedy, a diplomatic surge is needed to open humanitarian access and to stop the warring parties from committing further atrocities. In the meantime, international donors must increase humanitarian assistance where it can already reach those in need.

Refugees International would like to thank Fidele Mbaiouassemnodji, an independent Chadian humanitarian consultant, for his support in the research trip and interviews informing this report.

Featured Image: Manahim was a teacher in Darfur until she fled to Chad in April. Now she volunteers teaching in a school for refugees. She says there are many skilled women among the refugees like her who are eager for opportunities to support themselves.

Source link : https://www.refugeesinternational.org/reports-briefs/bearing-witness-atrocities-and-looming-hunger-in-darfur/

Author :

Publish date : 2024-02-01 08:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.